On a nippy November evening in Ajmer, minutes after an unexpected drizzle left Mayo College’s Mughal Gardens smelling sweetly of wet mud, Rkive City, the post-consumer design and research house founded by Mayo alums (and brothers) Ritwik and Aarav Khanna, staged a show that was equal parts fashion moment and homecoming. The school’s main building—where generations of boys have gathered for classes and morning assemblies—loomed in the background as alumni, friends, and collaborators trickled into their seats.

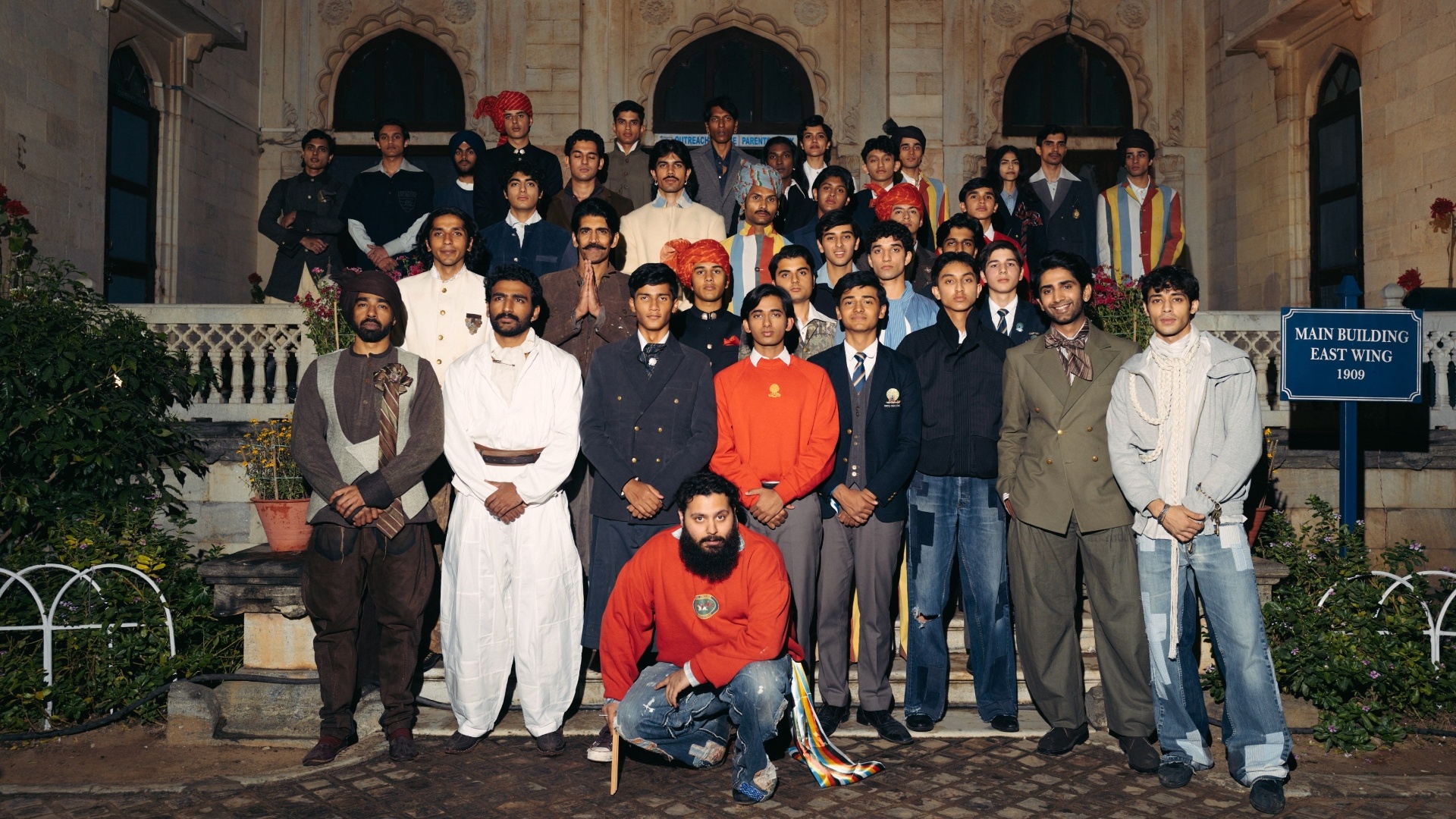

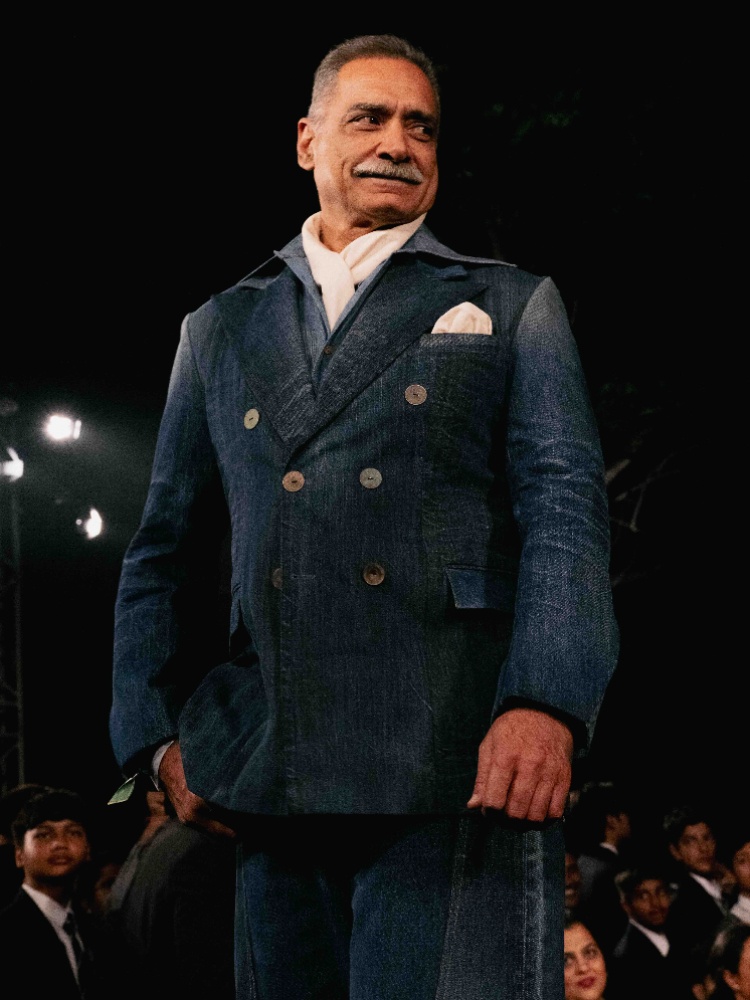

Rkive City has built its reputation on an almost stubborn commitment to working with only post-consumer textiles, repairing, reviving, and reimagining garments that already exist. But this collection, created entirely from discarded uniforms, decades-old tents and curtains, and whatever the campus linen room had quietly hoarded for years, was its most personal yet. It was a presentation stitched equally from memory and material: exaggerated, upturned cuffs inspired by archival photos of past students, carpenter trousers cut from old grey uniform fabric, blazers reimagined in corduroy instead of polyester, and sharp ceremonial wear that wouldn’t look out of place at even a wedding. The runway cast included models, students, alumni, and even retired teachers—a living timeline of the school itself.

But what made the whole scene even sweeter was the quiet full-circle moment unfolding behind it: years before founding Rkive City, Ritwik was the kid secretly selling screen-printed custom Mayo merch out of his dorm room. Now, eight years later, he’s back on the same campus staging a full-blown fashion show, this time with the faculty’s blessing—and a traditional brass band scoring the entire thing.