A new day, a new chapter

The next morning, sunshine poured onto Paro, and just as the new day dried the road, little did I know it would brighten my perspective too. Paro is one of those positively idyllic places—planes float through the valley like black-necked cranes every hour or so, dancing through the mountains in the act of one of the most difficult landings in the world. As one passed, I looked up and noticed Parv, one of the younger riders, who also came alone, perched on a stone wall, sketching the valley in his journal. But what warmed my heart even more was that, as our fellow bikers trickled in for breakfast, they gathered around and encouraged him through back pats and compliments. And then, they turned to me.

I was not sure what happened overnight, but I suppose an unspoken consensus had been reached that my reading was passion over performance, or that we all simply got a bit more used to each other and the questions turned from ‘why are you reading?’ to ‘what are you reading?’. In fact, bringing a book was the most social thing I could do on this trip. From the stone steps of our hike to Tiger’s Nest Monastery to the post-trek communal hot-stone baths steeped with Himalayan herbs, my fellow riders seemed to be far more comfortable around me as I read—just as I was happy to politely put the book down and chat, learning about their lives and families or what they liked to read, and then return to the pages of my murder mystery during comfortable silences.

The middle path

Perhaps my favourite moment of shared calm was deep in the Trongsa Valley at Wiling Cafe, a location often referred to as ‘Instagram gold’. Here, guests get a 50-metre-high cliffside waterfall to themselves, which forms a mountain stream that winds through the leafy property. I plopped myself on the lawn, knackered from the ride and bowled over by the beauty about me, and slowly dug into my book. A bunch of riders from Bengaluru sat next to me and took a nap. It reminded me of my school days. At first, you’re petrified of sticking out, but once you show that you’re comfortable in your own skin, people seem to gravitate to that grounded nature. Maybe it sounds silly—a grown man happy that other grown men were happy to flop next to him on the grass and quietly enjoy the fine mist carried over them by a soft mountain breeze—but it was a truly peaceful moment to the point I wound up napping face-first in my book until our lead rider gave me a shake.

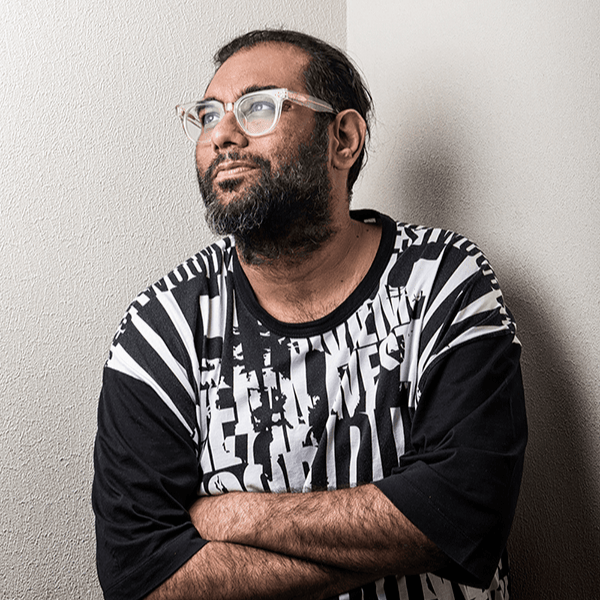

Later on, at a lonely one-pump petrol station on the road to Phobjika, where our long line of bikes had formed a queue that took over half an hour to filter through, I looked up from my book at the back of the line to see a fellow rider, Yasir, spontaneously fist-bumping a child in an adjacent car. Our local lead rider, Kunsung, jumped off his bike and shuffled over to the child in a full bow, the palms of his hands tightly clasped together. He stopped right before the window, and received a chubby hand placed atop his head in the form of a blessing. Before I fully registered what was happening, I did the same, as did the other handful of stragglers about the petrol station.

We learned from Kunsung, who looked like cool holy water had just been splashed across his face, that the yellow-robed child was the reincarnation of a recently deceased Rinpoche—a term that loosely translates to ‘precious one’, a respectful reference to certain accomplished lamas, abbots, and religious teachers. Even for a local, our travels in Bhutan were proving to be legendary. “We are very lucky and fortunate to have seen him,” extolled Kunsung. “It [lifted] our heart, we got a blessing. So, we feel happy. We then have positive energy. We are not enlightened; we make mistakes, and we learn from them… We don’t have to focus on being perfect, just the middle path, to remember our impermanence—one day we have to leave this beautiful world, so we should enjoy life in a good way.”

Carpe diem

I took Kunsung’s words to heart. Their echo etched in my memory as I savoured my surroundings over the onward journey: when I discovered a hidden forest clearing to drink in the hypnotic churn of water-powered prayer wheels pushed by a chilly stream flowing from Jigme Singye Wangchuk National Park; explored Bumthang’s natural-dye frescoes of tigers that swirl across the walls of Wangduechhoeling Palace Museum, which once served as the kingdom’s first seat of power; and stumbled across an ancient scroll ceremony at Gangtey Monastery, where a tennis-court-sized religious document is attached to a system of timeworn pulleys and hefted over the facade of the prayer hall. But just as lovely was reuniting with everyone in the evenings over a crate of beer to swap the day’s stories, spicy 2 pm chips, and banter around bonfires.

On one such night, the group laughed until 10:30 pm, which is the sleepy-valley equivalent of 3 am—much to the chagrin of the tour-bus load of elderly American tourists who shared the remote Odiyana guesthouse with us in the black-crane wetlands of Gangtey. My sympathy for them was perhaps downsized by the sounds of my poor snoring roommate, who was now suffering from a cold, which made his late-night bellows almost seem angry in volume and vigour. But just as you can’t blame a man for having sleep apnea and being sick, you can’t blame bikers for bonding after a day of riding, even if they are a tad perfumed by K5 whisky and last-resort Navy Cuts.

On the last full day of riding in Bhutan, we stopped in Ura village, where red-billed chough called to each other from intricately carved window sills painted with sew meto, or ‘flowers of clarity’, for a hearty lunch of rich ema datsi. Soon after, I found a spot on the shaded steps and was a few chapters into a new book when I heard the soft notes of Bhutanese pop song ‘Bum Jarim’ waft over the hillside. Some of the riders had convinced our guides to sing their favourite love songs, and before long both the riders and the guides were singing ‘Jab Koi Baat Bigad Jaye’.

Nine days into the trip, I figured I had likely misunderstood the ‘why are you reading?’ on day one, when all my companions were trying to do was let me know that I was welcome to join in the conversation, not coercing me to be in one. For the whole trip they had proved that good company is just as good an escape as a good book: Vandana, who had stubbornly chased down the waiters who forgot my chowmein order on a cold wet day, standing in the kitchen until my hot food was finally delivered; Gokul and Mahaveer dancing under waterfalls; Kathy and Sam, who slipped prayer beads on my wrist; or Malika, who gifted me tea for my grandma. Even when I tried, I couldn’t really begrudge the man who stole my sleep for over a week, his presence sparking a smile as frequently as his pegs sent sparks flying when he hit the hairpins. Once again recalling Kunsung’s sage-like talk, I realised I had probably misread that interaction on that overcast day because I was blinded by my own impermanence the moment I rode into Bhutan.

About a decade ago, I got my first big break in Bhutan by writing a story on how the death of an adventurer resulted in the nation’s first skate park, which landed me my dream job at National Geographic Traveller. And I think as I crossed the border for the first time since, I immediately began to miss that bright-eyed writer with a far more optimistic hairline and outlook on life. But even a slow git like myself will eventually realise getting stuck in the past isn’t the same as looking inward. I just needed to admit I was blessed, looking over what very well could be the prettiest glen in the world, surrounded by salt-of-the-earth bikers. So, I did the only thing that made sense. I got up and sang out of tune on the side of the road with relative strangers, and we all, even if just for a moment, lived in perfect harmony.