Winter settles over Chandigarh like an empress reclaiming her kingdom. Le Corbusier-style homes warm up to the sizzle and hiss of fireplaces even as the romance of sarson and makki is rekindled. Kids in hoodies push scooters in kachnaar-pink public parks. Meanwhile, the air in a hotel suite is thick with anticipation. All await Harmanpreet Kaur, reigning empress of world cricket and pride of Punjab.

When she finally walks into the Radisson with best friend and manager Nupurr Kashyap, the security stationed outside, Harmanpreet looks serious, almost severe, silencing a room noisy with caffeinated talk just a moment earlier. I bravely present my battered copy of The Laws of Cricket; she has, after all, rewritten the rules of what can no longer be called just a “gentleman’s game”.

“Where’s this from?” she asks, twinkly eyed.

“Lord’s,” I reply.

“You can have it if you like,” I add, willing to offer my entire library if it pleases the kaptaan.

“No, no,” she smiles, signing the inner cover.

What played out right after midnight on November 2, 2025, can never be fully explained.

The World Cup-winning moment. It felt like the moon landing of women’s cricket in India, if you’re looking for scale. A comprehensive shattering of the grass ceiling, if you’re game for a pun. It’s noteworthy that Central contracts were awarded to women cricketers only in 2015, and the Women’s Premier League (WPL) came into being only in 2023. Even now, money still flows largely into the men’s game. I remember Harmanpreet’s famous words after winning the first-ever World Cup for women’s cricket in India: “Without [the trophy], the revolution, the change we want won’t come.”

The impact the win has had on the collective psyche of a male-dominated nation is incredible. And Harmanpreet Kaur, known for her fearless brand of cricket, has played a key role in this gradual, and then sudden, shift in attitudes towards women in sports. Her match-winning 171* off 115 balls in the semi-final of the 2017 World Cup against Australia forced the nation to take notice. In the WPL, she led the Mumbai Indians to victory in 2023 and 2025. And in the 2025 World Cup, her team went through three consecutive defeats in the league stage only to come back with a thumping semi-final win against Australia; she played a captain’s knock of 89 off 88 balls in that game. In the final, it was only fitting that Harmanpreet would seal the victory against South Africa with a catch at midnight announcing the revolution.

I cry a lot and very easily. I tell the girls they must do the same whenever they need to. If you don’t express your emotions, they gather inside and create trouble. You need to let it out and move on”

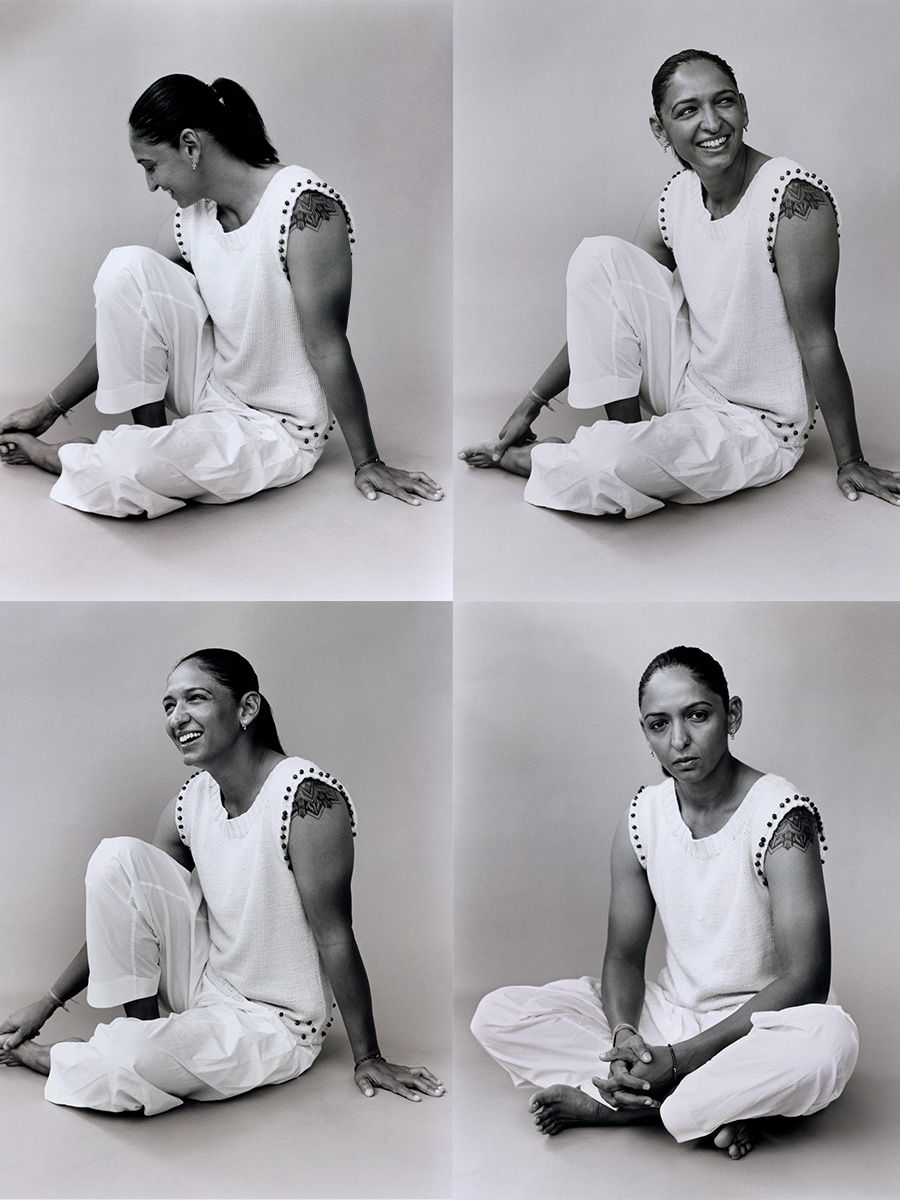

Yet sitting across from me is an unassuming athlete going through the rituals of a photo shoot with stoicism. “Bas karo, bhaiyya,” she pleads as an eyelash curler does its thing. “Let the tear fall, no problem,” HMU pro Mitesh Rajani says in his endearingly flamboyant way. I ask Harry di—as her team calls her—about tears; there were many on display during the tournament. “I cry a lot and very easily. I tell the girls they must do the same whenever they need to. If you don’t express your emotions, they gather inside and create trouble. You need to let it out and move on.”

Not what ambitious women are usually advised to do in public. Was she a rulebreaker right from her childhood days in Punjab’s Moga district?

“Growing up, I was never stopped from doing what I wanted. I played cricket constantly with the boys in the gully. Hearing other girls complain about restrictions placed on them made me realise that my upbringing was not the norm,” she says, lauding her supportive parents. It couldn’t have been easy. Her father, Harmandar Singh Bhullar, worked as a clerk in the district court; the family’s modest income was supplemented by farming activities. Harmanpreet’s friend Hartaj’s older brother, Yadwinder Singh Sodhi, was her early coach. I can’t resist asking if her backlift was glorious even in those days. “Yes, I always did that well. But I have had to work on my cover drive and other offside shots,” she concedes.

For a girl in rural India, with two younger siblings to look out for, escaping the pressures of societal expectations is rare. But Harmanpreet assures me there was no stress on that front. “In fact, even my mother [Satwinder Kaur] learned to cook properly late in life. And my dadi always wanted me to join the police force.” Harmanpreet currently enjoys the prestigious title of DSP in the Punjab Police, earned via the sports route. But when she moved to Mumbai in 2014, it was as a junior employee of Indian Railways, championed by former India captain Diana Edulji.