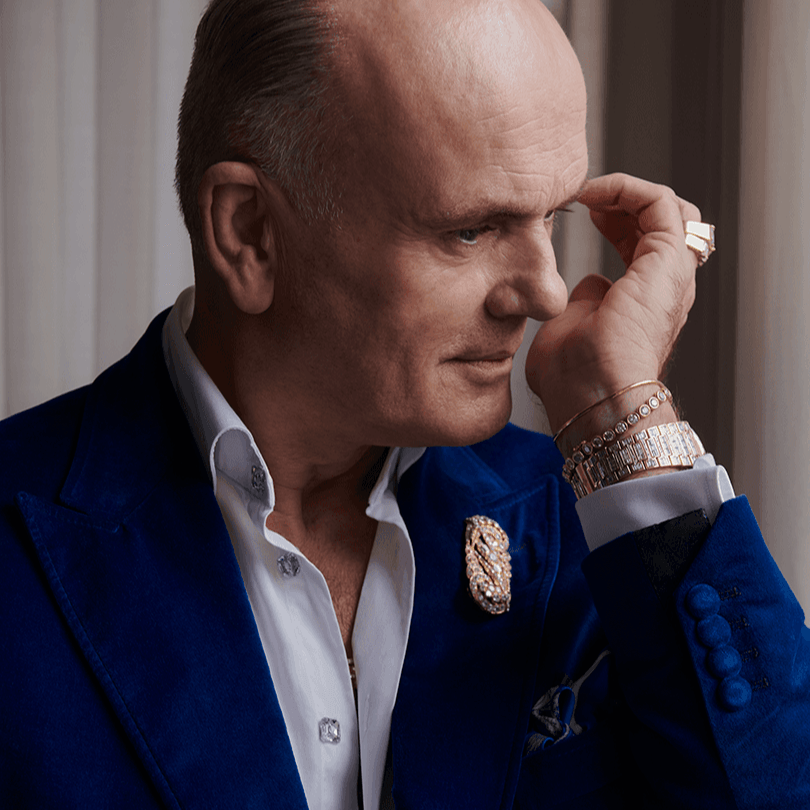

We choose our scents according to season, occasion, time of day, place, mood… They sometimes reflect who we are, and sometimes, who we’d like to be. Ever since he launched his eponymous brand, Kilian Paris, perfumer Kilian Hennessy has mastered a way to bottle a gamut of personas—take a cue from scents with names like Love, Don’t Be Shy; Dark Lord; Good Girl Gone Bad; Sunkissed Goddess; Sacred Wood; Black Phantom; and Moonlight in Heaven, to name a few. The scents are bold, all-enveloping, and feel like a treat, marrying notes like marshmallow and neroli, ambrette and carrot seed, pepper and vetiver, incense and cedarwood, rosemary and mandarin…

Fifteen years ago, Kilian Hennessy of the house of Hennessy, the legendary cognac makers of France, chose to follow his nose instead of joining the family business. The woodsy smell of oak barrels and childhood memories, though, seeped in, leading to the creation of his uber-luxurious signature fragrance, Angels’ Share. (There’s the anecdote of visiting the cellars with his grandfather as a child and the memory of the latter referring to the mysterious evaporation of eaux de vie from the barrels as “le part des Anges”, or angels’ share.) Not surprisingly, it’s Hennessy’s favourite scent—it took him 12 years to create.

Now, Kilian Paris is set to launch its new fragrance, Angels’ Share Paradis, in India. Drawing from Angel’s Share, the new scent, created by Kilian Hennessy in collaboration with perfumer Benoist Lapouza, announces itself with notes of cognac oil, tonka bean, cinnamon, oak and raspberry liquor, proceeds to Bulgarian rose oil and cinnamon bark oil, and rests in a dry-down of sandalwood album oil and tonka bean absolute. Bonus points: The crystal bottle, designed like a drink tumbler and topped with a natural oak cap, is refillable.

Over a video call from Paris, where it’s 4 o’clock and flatteringly sunny, Kilian Hennessy discusses his new fragrance, his feelings on citrus notes, and the importance of a good beginning.

In the past, you’ve spoken about the varied influences that spark some of your signature scents, from a Klimt painting to Turkish coffee to a dessert in Bangkok. What’s the story behind Angels’ Share Paradis?

Angels’ Share Paradis is an extrait de parfum of Angels’ Share. The way I created it was by getting onto the shoulders, if you will, of Angels’ Share. It’s exactly the same formula but I tried to bring in a few different things that I think customers expect from an extrait de parfum. They expect a higher concentration, and Angels’ Share Paradis is 20 per cent more concentrated than Angels’ Share. I think they expect more quality, and, associated with quality, more projection in the air. So, all the ingredients that were very expensive in the formula, like the tonka bean absolute, are there, but also all the ingredients that give a lot of projection and diffusion in the air have been drastically increased, like ambroxan, maltol, oak moss…

And it is called Angels’ Share Paradis because at the house of Hennessy, the highest quality of cognac is the Hennessy Paradis. And when you smell and taste the Hennessy Paradis in comparison with the Hennessy X.O, for example, I found there’s a little hint of raspberry in the Paradis, which you don’t have in the X.O. And a little touch of rose. That’s why I added the Bulgarian rose as well as two raspberry notes. We used a new technology developed by Givaudan, called Delight, which allows aromas from the food industry to be adapted for the perfume world.

One of the ingredients in Angels’ Share Paradis—sandalwood—is increasingly getting harder to obtain. You’ve spoken about this in the past too. How is the perfume industry adapting to this shortage of ingredients?

There is some sandalwood album from Australia in Angels’ Share Paradis. As you know, the most beautiful sandalwood is the one from Mysore, which we are not allowed to use in the perfume industry. But 30 years ago, the industry started to search for an environment and water and soil conditions that would be very close to Mysore, and they found a location in Australia. But the quality of the sandalwood from Mysore also comes from those very old trees that are 40 years old; with time this sandalwood develops a milky, very sensual facet. And little by little, now those trees from there that have been planted in Australia 20 or 30 years ago are starting to deliver something close to the sandalwood from Mysore.

What, according to you, is the most crucial stage in the development of a fragrance?

There are a lot of important stages. I would say the most important is the beginning, which is to learn your craft, to learn the 3,000 to 4,000 ingredients that are available in the perfume world, because if you don’t learn what materials are available to you, then your creation process is limited to just a few hundred ingredients.

Then I would say creativity, imagination. You know, every musician will always tell you that they hear the music before they write down the notes. And it’s the same thing for me. I always smell the scent, in a way, in my brain before I start working on it.

And then, I would say, patience. Sometimes it can take up to two years to finalise a perfume.

Your most well-known scents veer away from citrusy, transparent notes towards the headier, more woodsy territory. What’s your approach to the notes that you select for your perfumes?

I love citrus notes. I used them in Bamboo Harmony. I used them in Kologne. I used them in Moonlight in Heaven. I just realised that customers don’t seem to be coming to me for citrus notes. I think they expect the notes from me to be more narcotic, white florals, woodsy, ambery, leathery, animalic, sexy notes, rather than the clean and fresh.

What kind of notes do you tend to gravitate towards?

I always come with a script, and the quintessence of the script of the story I want to tell comes from the name. Once I have the name, I start working on the perfume, not before. And what I’m trying to do is express the emotion expressed by the name. So, the name can take me to one territory of notes or another. You mentioned Gustav Klimt earlier. I love Gustav Klimt, but I especially love his Byzantine period, when he was painting with gold leaf. For example, ‘The Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer’ or ‘The Beethoven Frieze’. The whole period. I created Woman in Gold inspired by Gustav Klimt’s gold period. And the idea for me was to use the same colour codes in ingredients that Klimt used in his paintings, which was gold leaf, black and white, and that’s it. So, what does black smell like to me? What does white smell like to me? What does gold smell like to me? And this created a canvas. And I started working around that canvas.

Could you elaborate on the impact of legendary perfumer Jacques Cavallier-Belletrud on your journey as a perfumer?

He is one of the greatest perfumers of our generation. Today he is the in-house perfumer for Louis Vuitton. But when I met him, he was a very young perfumer. He was 32 years old. He was working at Firmenich in Paris and I met him because the president of Firmenich was a friend of my grandfather, so my grandfather said, go meet my friend, because I was writing my thesis on perfume. At Firmenich, I was told, “Well, for your interview, I will not bother one of my great perfumers, but I will ask a young one to come help you,” and he called Jacques. I did the interview with Jacques and it clicked very, very quickly. He said, your questions are great, and then he said, “If you want to do your end-of-university internship (which was five to six months), I’ll take you with me.”

So, I did my internship for six months at the end of university with him and from then we never left each other. I have created many perfumes with him, and over the years he became, very quickly, my teacher in perfumes. I did a nose school during my fifth year in college and by the end of that nose school, I probably knew maybe 300 or 400 ingredients, but with Jacques I went from 400 to, I don’t know, 1,500, and was starting to learn the combination for how to make a rose without using rose, how to make jasmine without using jasmine and so on. So, yeah, it’s been a long friendship. We met in 1994, so over 30 years.

Can you recall a few of your most favourite scent memories?

When I started studying raw materials, there were a few ingredients that made me fall in love with the perfume world. One of them was the sandalwood from Mysore. One was galbanum, one was a synthetic note called methyl octine carbonate. There was another synthetic note, a white musk called galaxolide, and a natural oil named osmanthus absolute, which has an apricot, violet and other facets all wrapped into one. There are so many...

What are the non-olfactory influences that affect what scents you make?

A lot of things have influenced me. One day I was having a Turkish coffee on a terrace in Istanbul—my absolute addiction, I love Turkish coffee—and I realised that the taste was very unique. They had added cardamom to the Turkish coffee, and I thought this was an amazing combo. And that led to the creation of Intoxicated. We’ve talked about Klimt. We can talk about a dessert that I discovered in Thailand, which was a sticky rice infused with coconut milk that is served with a scoop of mango ice cream, and that bottle of flavours in the mouth coming from the cold ice cream and the hot rice and the exotism of the mango with coconut oil…I just found all those flavors so wonderful that I immediately started writing a little formula to express that flavour. Angels’ Share, which is today is my absolute top seller, is my olfactory memory of the Hennessy cognac cellars when I was visiting them with my grandfather. Every scent has an inspiration that comes from me. I’m not too interested in things that are marketing-oriented or in doing something just to tick a box, you know? It’s really about what I want to express as an emotion right now.