Last month, when Adolescence dropped on Netflix, predictably, the school WhatsApp groups—where outrage never sleeps—were abuzz with conversations about how we need collective action on limiting access to phones and social media. There was a recent poll on one school group on the appropriate age to give the kids a smartphone; I think the consensus was sometime between the ages 13 and 16, ideally later. I kept very, very quiet. I gave my son a smartphone this year. He is 11. Yes, I know it’s a bit early and I haven’t really announced this outside my family group, but his phone is precisely for that purpose—to stay connected to all of us at home. And yes, all the due child lock essentials are in place. I am not that lackadaisical.

The truth is, my kids have had screens for years—first as a mealtime distraction when they were babies, then for nursery rhymes, and so on. You get the picture.

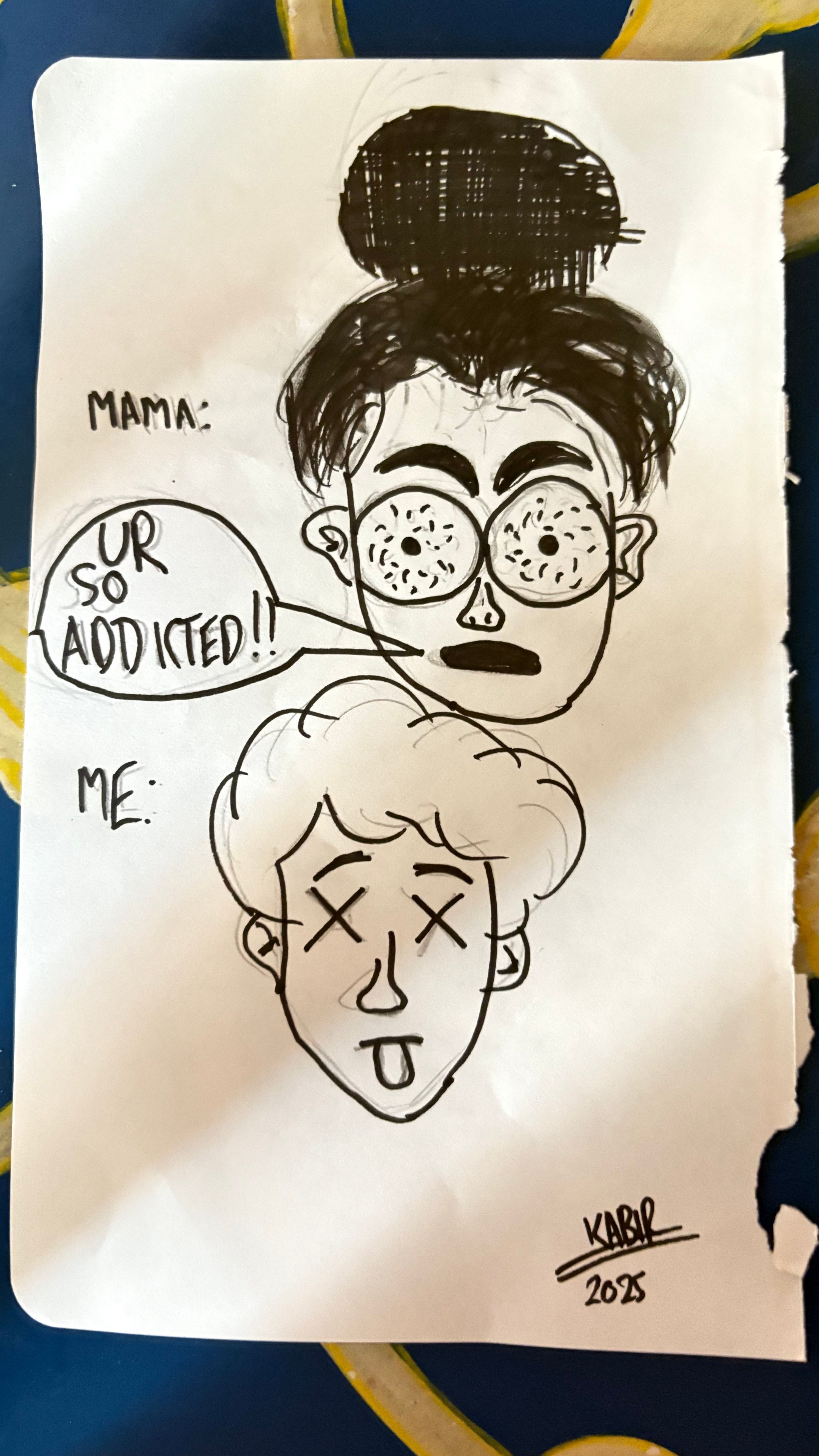

When I look at my children now, I see them as hyper-precocious creatures who seem to know everything about everyone. My daughter’s search history has everything from “how to use a 3D face roller” to “how to draw Sanrio’s My Melody” to “Anna McNulty cartwheeling”. She is eight going on eighteen, her tongue dipped in the syntax of YouTube and Instagram. “Mamma be like—”, “Kabir be like—”.

I flinch. My blood churns with this language. Once, I edited a magazine. I wrote a book—literary fiction, no less. And yet here I am, deciphering memes, parsing TikTok speak, watching the rise of Gen Alpha, a generation fluent in serums and sheet masks. When a friend asked my daughter what beauty content she watches (Gen Alpha apparently is the new target consumer!), she promptly replied: Drunk Elephant, Laneige, Summer Fridays, Rhode, Rare Beauty, gel nails/nail art, skincare fridge. A lot of that is probably to be blamed on me because of the nature of the work I have done and continue to do—the joy of receiving press samples and sharing it with my little girl.

When we were young, our parents worried about television, about violent games and flashing screens. Yet here we stand. Mostly whole. Mostly alright.

My son’s feed seems more straightforward. Football, drums, and a hundred different ways to cook butter chicken. Sometimes, scrolling through their history, I feel relieved—they’re still young, and (mostly) innocent. Other times, I’m paranoid they’re growing up too fast and I don’t spend enough time with them when they are growing up. But mostly, I’m scared. I’m scared because I was like this. Hyper-aware. My best friend and I started watching The Bold and the Beautiful and Santa Barbara when we were eight and Star TV had just entered our living rooms. I started playing prototypes of video games my uncle brought back from Yemen when I was six. So, I worry that it’s in their goddamn genes. When we were young, our parents worried about television, about violent games and flashing screens. Yet here we stand. Mostly whole. Mostly alright. Right?

At first, I couldn’t get myself to watch Adolescence, knowing what happens in the show. But the chatter about it was so loud that I took a deep dive into Reddit’s alternative universe, reading every thread, analysing every pivotal scene, and spiralling into the same fears every parent has right now—do we really know what’s going on in our children’s lives? How much policing is too much? Where’s the line between guidance and suffocation? Try as I might, I can’t go cold turkey on screen time with my kids. But then I look at my own life and how much of it I live on the phone and feel that it’s simply unavoidable.

Each time I tried taking the phone away, the kids managed to find a way—slipping through the gaps, shapeshifters in the digital mist. They are born into the algorithm, while we, relics of an analog past, fumble with screen-time limits like hopeful amateurs. It seems like a constant give and take, an unending endeavour to strike a balance, one that keeps shifting. I deleted Roblox, but couldn’t delete the iPad. I don’t have the answers. I don’t think I ever will. But in a world sharp with edges, how do we teach softness? How do you screen them from crazy, filthy things they are going to experience without a TW kicker?

When I look at Stephen Graham’s character in Adolescence, he seems like a decent dad—comes home, puts dinner on the table, the usual. Can he really be faulted for what happened to Jamie? When things fall apart, blame is an easy thing. Responsibility is the harder burden. The weight of keeping an even tone when you want to scream, of carrying a storm inside your chest and calling it love.

It’s not just about raising boys to be better or teaching young girls to be nicer. It’s about letting our children know that there is no need to suffer a bully quietly.

But there are some things we can do as parents and teachers. We need to be more curious about our children’s lives—the ones they will live online, and especially the unseen lives they lead. A bully is a bully, whether behind a screen or in a schoolyard. The warning signs are the same—a child silencing their voice or raising it to wound another. It’s not just about raising boys to be better or teaching young girls to be nicer. It’s about letting our children know that there is no need to suffer a bully quietly. Because in the end, communication is a superpower. And love, when wielded well, is the greatest shield of all.

As parents we tend to think our kids are incapable of doing bad things. In this, as in everything else, we tend to underestimate them. If we don’t acknowledge and embrace their imperfections, we fail as parents.