Everyone will agree: the high of success feels great. But the sting of failure? It can blow your self-worth. But if the wise are to be believed, there’s a science to failing well. Booker Prize winner Arundhati Roy talks about it in her recent memoir through her Rhodes scholar-turned-pickle-baron uncle—“the grandest failure of them all” who made “failure sound fascinating, even worth striving for”.

Failure, the one thing most of us try avoiding most of our lives, has a way of teaching us a lesson or serving as a stepping stone to incredible success. What would a Massimo Bottura dinner be like without his iconic Oops! I Dropped the Lemon Tart—a deconstructed dessert that is as much a legend as the chef himself—which came about when his sous chef accidently dropped a lemon tart.

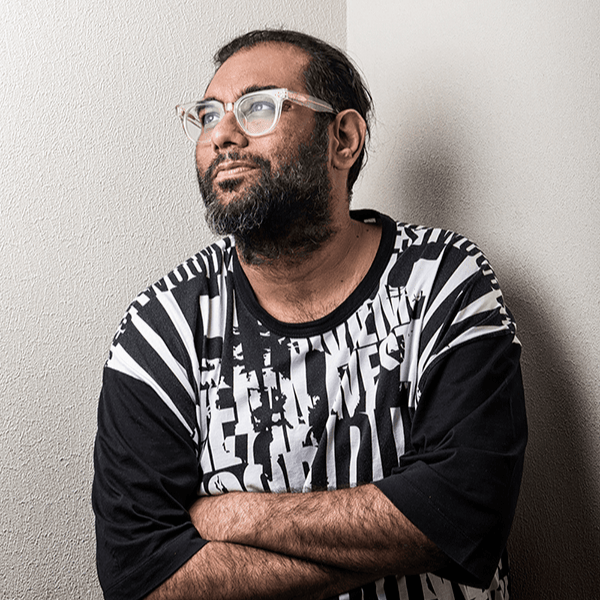

Sometimes, the kitchen can produce breakthroughs that go beyond a single plate. “I did a lot of supper clubs in my test kitchen for almost a year before Mizu Izakaya started in Worli in 2019,” shares Lakhan Jethani, co-founder and executive chef of Mizu Izakaya in Mumbai and Goa. “We hosted meals without really understanding the importance of consistency. The food was good on day one, but by day three we had issues with prep, sourcing, and team communication. Guests noticed the drop, and I was crushed.” It all came crashing down one night when they had 15 diners to feed and just two gas burners. Half the group was served on time, while the latecomers had to wait almost an hour and a half for their meal. Jethani knew that was unacceptable for a hospitality brand, but he didn’t give up: “I learned that besides great food, systems, discipline, and respect for every detail are equally important. That lesson shaped the way I built my kitchen today,” he adds.

Most chefs know this well and embrace these mistakes—because for every standout dish, there have been months of kitchen experiments. But it’s not just the standout dishes that hold value. From a condiment that paved the path to the culinary arts to that one dessert that came with a side of a big life lesson, here four chefs share the culinary flops and misses that helped them build a healthier relationship with mistakes.

Failing at toum made me a chef

by Sarita Pereira, chief executive chef and founder, The Lovefools, Mumbai

“The dish that failed me time and again is what set me on the path to becoming a chef. I became obsessed with mastering the toum, an impossibly light and airy Levantine (Lebanese) aioli. I watched countless YouTube videos, tried every method—modern and traditional. I Googled ‘How can one mix oil and water?’ and that introduced me to the science of emulsification. That further led me to a Harvard lecture series on food, where Michelin-starred chef Fernando Jubany spoke at length about emulsification. The lecture was in Catalan, a language I didn’t understand—but by the end of it I finally knew how to make toum. I was so moved by the chef’s passion that I decided to write to him. By then, I was clear: I wanted to leave behind everything I had built in advertising and pursue a calling in the kitchen. I even considered applying to Le Cordon Bleu or Alain Ducasse for a six-month programme. And then, serendipity stepped in. Almost a month later, after my letter had been translated, chef Jubany replied. He agreed to take me on as a stagiaire. And that’s how the failure of making toum gave birth to The Lovefools.”

Burning an omelette sparked precision

by Vedant Newatia, founder and head chef, Atelier V, Indore

“At L’Oustau de Baumanière (then a two-star Michelin restaurant) in Les Baux de Provence, France, where I was staging, I once had breakfast duty—cooking omelettes from farm-fresh eggs brought in each morning for the guests staying in the suites. One day, I let an omelette go slightly brown, and the chef was furious. He told me I’d never touch a pan in that kitchen again, and I could peel and cut vegetables for the rest of my stage. I asked him for one more chance, and after that day I’ve never made an omelette with a hint of browning. For a six-month stage, I handled the entremetier station (the station for eggs, vegetables, soups, and lighter hot dishes). But it was that failure that instilled in me an uncompromising respect for technique and precision, a lesson I carry into every dish I create.”

The Baobing that taught me to let go

By Martin Gomes, head chef, Siren Cocktail Bar, Bengaluru