It’s nice to know who inspired the character of Velutha in Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things. Or how her beloved uncle G Isaac—the Rhodes scholar known for such dinnertime utterances as ‘Isn’t it wonderful to have a god of wine and ecstasy?’, the sometimes villainous, often sparkling presence in their lives—became a character in the same Booker Prize-winning novel. Or the many intermissions that marked the decade-long path that led to the eventual publication of The Ministry of Utmost Happiness in 2017. Everyone likes being able to tug at the thread that binds a name on the page to its real-life doppelgänger.

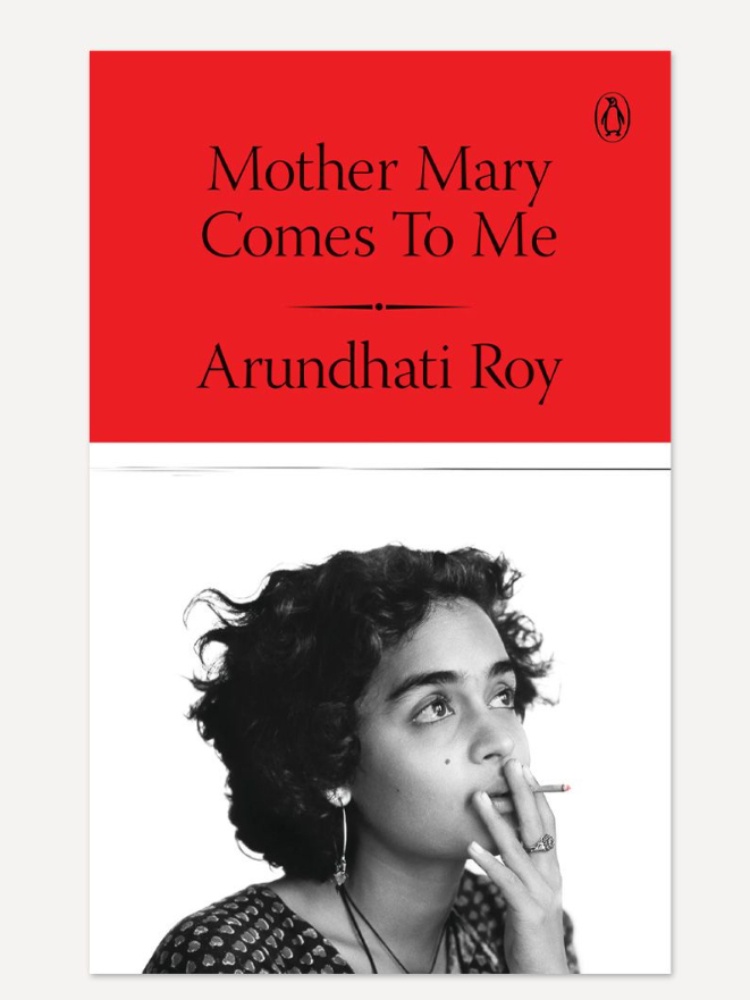

However, even if you leave the literary gold nuggets aside, what makes you keep turning the page in Roy’s recently released memoir, Mother Mary Comes to Me, is the figure in the title itself: Mary Roy, mother of Arundhati Roy (even if the former hated being described as such). There’s a line from the book that’s on the cover and keeps getting quoted by journalists in interviews and reviews of the book: “In these pages, my mother, my gangster, shall live. She was my shelter and my storm.”

While we all have a complicated relationship with our parents, in Mother Mary Comes to Me what we witness is a more consequential play of shadow and light—consequential for Arundhati Roy, for generations of her mother’s students at the pathbreaking school that she founded in Kottayam, and for us, the rapt readers, who are grateful for the writer all this shaped.

Mary Roy was a formidable figure. In the ’60s, she left her alcoholic husband and moved to Ooty with her two children, aged four and a half and three, and squatted in the family home there till she came up with a plan. Someone, who through sheer grit and an entrepreneurial spirit rare for the time, went on to establish Pallikoodam, the model school that revolutionised education in Kottayam district and the state of Kerala, on a barren hill that people believed to be haunted. She was the one who bought her daughter her first typewriter and introduced her to Shakespeare and AA Milne. Mary Roy moved the Supreme Court against the Travancore Christian Succession Act, which prevented women from inheriting property, and won—a fight spurred not just by the greater good but perhaps also by petty vengeance. Following her death in 2022, at the age of almost 89, she received a 21-gun salute from the Kottayam City Police.

Through this life marked by brilliance, if someone suffered, it was her two children, Lalith Kumar Christopher Roy (LKC) and Arundhati. Mary Roy was Mrs Roy for everyone, even to Arundhati and LKC—first in public, then, to simplify matters, everywhere. School report cards led to beatings or praise, and constant reminders of her efforts towards raising them began with “Speaking as your banker…”. Their father was a “Nothing Man”. Her favourite reprimand, “Get out!”, would become a source of mirth to her children and her loyal employees, but only much later.