If you’re in need of a mood lifter, look up author Mahesh Rao on Instagram. Just last week, soon after his novel Half Light released, Rao shared a video of a book launch with the caption “However grim life looks, at least your own uncle didn’t throw eggs at you at your book launch” on his highlights.

“It’s my water-cooler moment. [For] those of us who work at home, it’s very isolating. I treat Instagram very much as those water-cooler moments when I’m sharing the ridiculousness of life. It’s very sweet when people say they enjoy my Instagram stories, but I really just do them for myself, to give myself a break from work. It’s a kind of shop window if you like, and all of us do a certain amount of window dressing,” he says. Other gems in the recent past have included “Bedbugs”, which is his exploration of how the insect has been sexualised in Indian pop culture. Or the stories he uploaded while watching Chandigarh Kare Aashiqui (2021), which includes insights like the following: “This is why the olden days were better, you knew v little about stars and could just enjoy their films without wondering what they were doing with their wives’ breast pumps.”

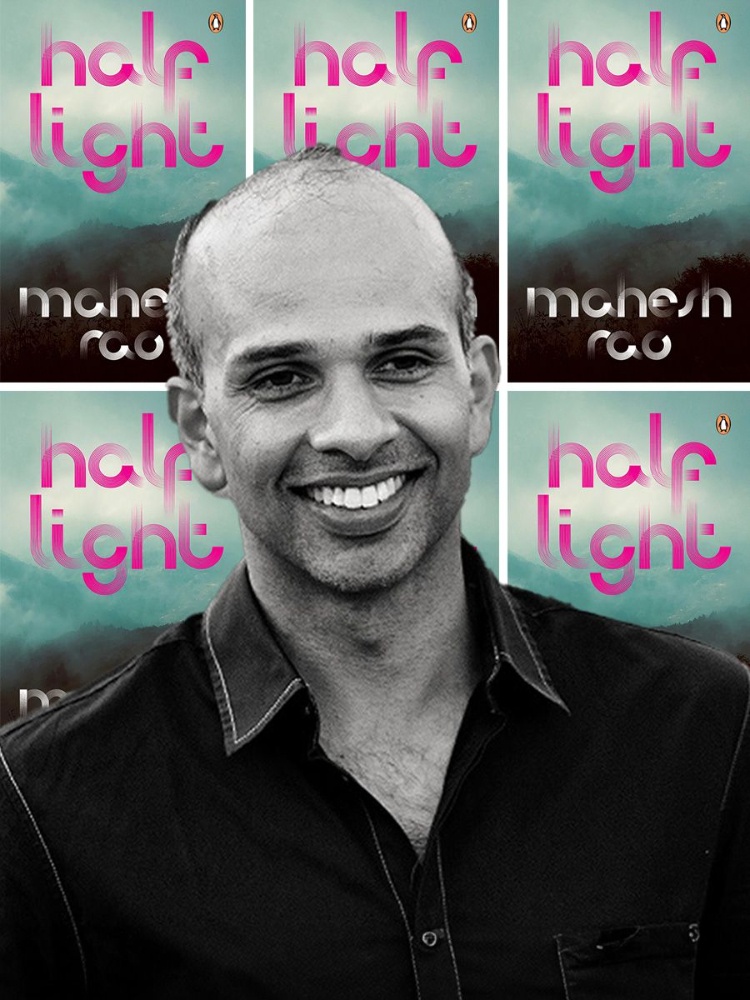

Very little of this silliness finds its way into Rao’s fiction, whose latest book, Half Light, is out on Penguin Random House India and is The Nod Book Club’s November pick. When he puts on his ‘author’ hat, Rao is all about literary fiction. Both his novels and short stories are characterised by elegant prose and nuance. Often, there are threads of humour, but they glint only occasionally. Unlike his Instagram updates, there’s nothing throwaway about the observations that Rao brings to his fiction. This is an author who takes the business of writing seriously.

After growing up in Kenya and living and working in the United Kingdom, Rao decided to move to India (specifically, Mysore) to write his first novel, The Smoke is Rising (2014). It’s been more than 15 years since then and Rao says he is now as at home in Mysore, where he spends most of his time, as he is in the UK. His sense of familiarity with India is evident in his second novel, Polite Society, which came out in 2019 and examines Delhi’s posh set and can be seen as a modern take on Jane Austen’s Emma. His latest novel, Half Light, explores sexuality and class in India and is Rao’s most accomplished work yet. He uses the prism of fiction to sensitively explore what it meant to identify as gay at a crucial moment in India’s recent history.

Half Light is about two young gay men, their complicated relationship with desire, and the impact that the 2018 ruling that decriminalised homosexuality has on them. Set in Darjeeling and Mumbai, the novel follows Neville, a Bombay brat who feels suffocated by his circumstances, and Pavan, a migrant who comes into his own in the big city. Through them and the spaces they inhabit, Half Light creates a portrait in miniature of Indian society. The novel captures the resilience and narrow-mindedness of the characters who make up the world of Half Light, recognising what makes them frustrating but also their capacity for grace.

Excerpts from our conversation:

Before we talk about Half Light, tell me how you see your relationship with India.

I moved here in order to write my first novel, because so much of being a writer is about economics, isn’t it? It was more affordable for me to work on my first novel here. I find being in India endlessly fascinating. We’re all thrown against each other all the time and there are literally hundreds and thousands of stories. Now, more than 15 years later, I’m much less of an outsider, but I’ve always got my eyes and ears open because that’s the gift of being here.

The first part of Half Light unfolds in Darjeeling and the second is set in Mumbai, where it goes beyond the usual SoBo neighbourhoods we’ve commonly seen in literature. Why did you pick these two locations?

One of the images that entered my head early on was of a group of people trapped in a dingy hotel. Quite often, that is the start of a murder mystery, but I wanted to use that to create this very claustrophobic, strange atmosphere in which two people who might have avoided each other under other circumstances would be forced to confront their attraction for each other. It’s a suspension of reality. What does it mean when it comes to desire, when it comes to courage, when it comes to transgression?

The other thing that was important about the Darjeeling setting is that a big part of Pavan’s character is his affinity to nature. So, Darjeeling allowed me to send him off to the forest.

There were two reasons to set the second part in Mumbai. The first was that I wanted somewhere very different from Darjeeling. If Darjeeling was cold, remote and bleak, I wanted this other place to be teeming with people, sweaty, hot, urban so that you’re talking about two completely different landscapes and geographies. Probably the more important thing about setting it in Mumbai was that the final scene was the very first thing that I wrote. For me, Marine Drive was the ideal location for the climax because it is beautiful, iconic, and all of us have been there, whether you’re from Mumbai or not. It’s for the whole city, the whole country perhaps. Anyone can go there. Anyone can sit by the sea. It really belongs to everyone and I needed a place like that for the final scene.

You’ve also set episodes of Half Light in far-off suburbs like Mankhurd and Kalyan. It’s nice to see these neighbourhoods in literature. There’s a lovely scene in which Pavan and a young woman he’s set up with, Anjali, look out of the window and see the suburb they’re in very differently. That was a very Bombay moment for me.

This is where my ambition goes—I write about places I’m not from. Somehow, I have this weird confidence that I can pull it off. I’ve actually never been to Mankhurd, but this was all done by watching videos, reading about it and so on. Kalyan I have been to, though briefly. I don’t think that should necessarily stop us. You’re trying to tell the truth and I think you can tell the truth about a place because you tap into something, because you’ve been somewhere similar, or you know enough about people to place them there and be able to tell the truth.

I wanted to talk about Mumbai in a way that acknowledges how most people can’t afford to live in the places that are featured all the time. The suburban neighbourhoods also had the attraction of being in a sort of flux, which I used in the scene with Anjali and Pavan. These are the fragments that slowly pull together and dictate where the story goes. For instance, Kalyan has a strange relationship with Mumbai, being a suburb, but it’s also its very own place. Anjali has a certain pride about where she’s from and that’s very much the story of the satellite cities. They’re coming very much into their own.

Before we talk about Neville and Pavan, can we talk about the women in Half Light? They’re all minor characters, but some of them play very important parts. And they’re all ultimately nice.

I do wonder about Audrey, if she is that nice. Audrey was really very difficult to write because in my head, for a long time, she was an extremely religious, overbearing, cold, distant mother and there are a lot of those in literature and real life. The thing that unlocked her for me was that I made her “hot”. When I first imagined her, she was what you’d expect of a Catholic auntie. It was too clichéd, but the moment she became “hot” and looked 15 years younger than her age, something unlocked and I suddenly had a better sense of who this person was.

But to return to the women more generally, this is the great patchwork of patriarchy: what will affect gay men will affect a great deal of women too. That’s what I wanted to look at, particularly with the Anjali character. Also—and I think many gay men would agree with me—right from the very first time we came into any sort of knowledge of who we were, our greatest friends, our greatest companions, our greatest champions have been women.

When did Neville and Pavan’s story come to you? Was it around the time when homosexuality was decriminalised in India in 2018?

No, it came later actually. [When the news broke that homosexuality had been decriminalised by the Supreme Court of India] I remember I was on my own at home. The news came out in the afternoon. But I remember, after that initial burst of euphoria it just felt like the waters closed again. Everything went quiet and I thought “What now?” Law is one thing, society is another. In that moment, I just thought these things are really interesting and someday someone should write a book about this, absolutely not thinking it would be me. The time that’s lapsed since then built the impetus to write this novel, talking about how it was before and what the change would mean to these two men.

Why did you pick Neville and Pavan as your heroes?

This novel is as much about class as it is about duality and desire. I was always very clear that the two had to be from very different backgrounds and that was really going to inform how they relate to each other. And it does. The stakes for Neville are not as great as they are for Pavan. What I really enjoyed doing was charting the shifts in the balance of power (between Neville and Pavan). Because as with any relationship, there is a power dynamic, whether that comes from class or gender or age. Pavan is six years older, and at that age that’s quite significant. But what I did was make him far more vulnerable than Neville, far more inexperienced, far more cautious, and that again tilted the power balance between them.

How did you want to show desire in this book? It’s such an important part of Neville and Pavan, but each of them has a very different response to it.

One way of looking at it was that these are two very different ways of being closeted. These are two distinct examples of what happens when a society forces repression on people. Pavan’s way is complete caution, complete secrecy. His desire is an incredible burden. When he moves to Mumbai, he has far more opportunity to act on that desire, but he skirts around it.

Neville’s is, of course, completely different. He’s utterly brazen, almost greedy, avid with desire. All of this is facilitated by technology. He can be on apps 24/7, meet people with the kind of enthusiasm and alacrity that just wasn’t available to previous generations. So, his way of being secretive is very different. He’s mainly secretive with his family but outside it, his sense of himself, his validation, his self-esteem comes from sexual conquests and the excitement of it. And it is all very exciting at that age, and later. The power of youth is intoxicating and he’s very much intoxicated by it.

Tell me about the ending. You chose to hold out more hope for Pavan and less for Neville, though he seems to be moving towards something better too.

I do think there is hope for Neville. He does something horrible, but he is filled with remorse and what it makes him do is decide to come out. We don’t know how it’s going to go, but we know change will come to his life and we hope that in the future he will be a better man.

With Pavan, he’s been forced into the light and he runs with it because that’s his personality. I hope the final scene encapsulated what a deep realisation of freedom can mean. There’s so much darkness in this country right now, but decriminalisation was the almost miraculous thing that happened here. Because there are places in Asia and in parts of Africa that still have section 377 or some descendant of it. We, this society, this country, did something amazing by ridding ourselves of that law. It is worth celebrating and that’s why that moment of hope is writ large in the final pages.

Humour often peeks through your writing, but you’ve never written a funny book even though you are hilarious on Instagram. There’s a dearth of humorous literary fiction. Would you ever consider writing an out-and-out comedy?

My feeling about comedy in literary fiction is that I think we are quite desperate for a laugh, but that temptation can be really dangerous. In Half Light, there were jokes that were taken out because I had wonderful editors who pointed out that either the jokes didn’t land or they felt inappropriate tonally with what was going on. I’m conscious of wanting to be the person who just wants a laugh, who wants a bit of an applause, and that might not serve the novel or the story in the right way. But you know, your natural voice is your natural voice and I think that my natural voice is wry. I think that does come across, especially in a lot of the socially observational scenes. But a straight-out comedic novel is probably not something I would even attempt because I do like those gut punches as well. I do like the sadness, the tenderness.

Mahesh Rao’s Half Light is out on Penguin Random House; ₹699/-