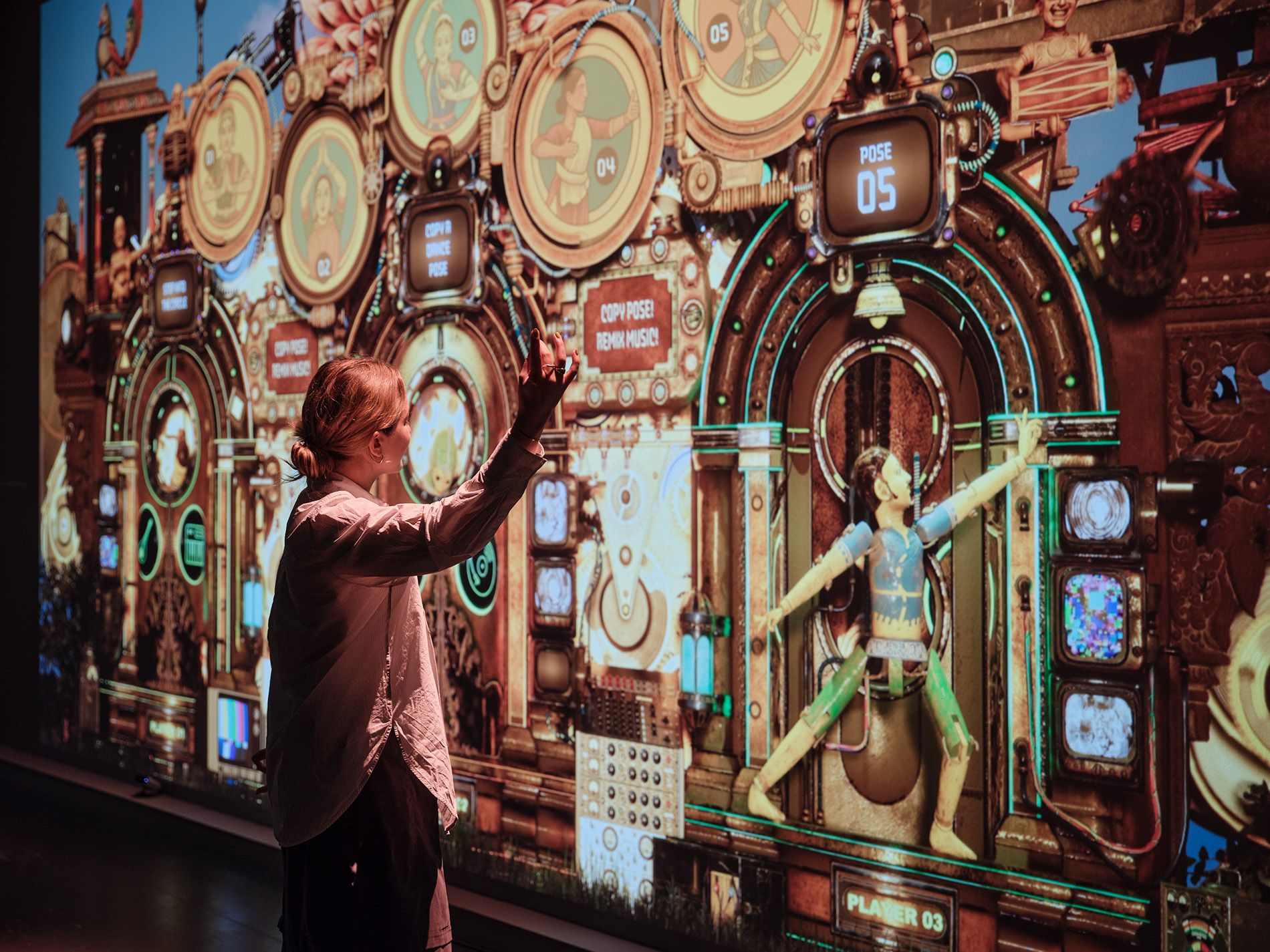

For artistes Avinash Kumar and Sri Rama Murthy—better known by their gaming alias Thiruda and Murthovic and together making up Elsewhere in India—showcasing their interactive piece ‘Resonance Continuum’ within the sacrosanct halls of the gargantuan, Brutalist force that is London’s Barbican Centre is their ‘we have arrived’ moment. For the museum’s immersive exhibition Feel the Sound, the Hyderabad- and Goa-based Mad Max-style artist group combine electronic music, performance, XR, gaming and art into a multimedia experience grounded in Indo-futurism.

I meet the duo days before Feel the Sound opens its doors to the public on May 22 to find out more about their elusive practice. This exhibition is a one-of-a-kind, multisensory experience that invites viewers to engage with how sounds shape our emotions, memories, and even physical sensations. Here, Elsewhere in India joins a series of international artists, including Japanese sound artist Miyu Hosoi, London-based dream architect Evan Ifekoya, and Barcelona-based Domestic Data Streamers, who are all bringing to life their multimedia installations on the potency of the aural waves that encompass us every day.

Murthovic and Thiruda—two men in their late forties obsessed with video games, AI, classical music and cyberpunk—are seated in the Barbican’s central courtyard, soaking in every drop of warmth the London sun has to offer. It is past noon, and this is the first coffee break the artists have had all day—between making final touches to their exhibition pieces, re-recording sections of their music, and offering previews of their work to visiting curators and art enthusiasts from across the globe. Past the cacophonous quacking of a few stray ducks by the pool, a gleeful (and overworked yet unexhausted) Thiruda peers over his steaming mug and takes me back a decade in time to make sense of the joyous, technical futurism their work revels in.

Born to fathers who served in the armed forces, both Thiruda’s and Murthovic’s respective journeys into the neon-tinted, raving world of electronic music was more accident, less design. “Honestly, I wasn’t into electronic music until I was 27,” Thiruda admits. “I was a trained designer—I studied toy design, and I’ve always been into visuals, games, and animation.” Working as a visual jockey in the mid-naughties with Delhi-based collective BLOT!, Thiruda met Murthovic through an underground circle of EDM fans who were slowly raising their heads in the country. An engineer by training, Murthovic was deep into his doctoral toxicology research when he decided to turn his side passion of deejaying at small gigs and office parties into a full-time profession. “As a young man, I felt confident about making a living off what I enjoyed. I was finding my footing, and getting paid. People were booking me a lot. I even had a manager,” he says.

Fresh from the financial slump of the early 2010s, Thiruda was running his own design-research lab called Quicksand. In 2013, his team got a small British Council grant to develop a prototype video game: an experiment that eventually snowballed into the creation of Antariksha Studio in 2016. It was around this time that Thiruda began collaborating with his mother, renowned Bharatanatyam dancer Jayalakshmi Eshwar from Chennai’s Kalakshetra. One of her shows in 2011, Antariksha Sanchar, explored Indian mythologies of flight—think Vimana-style flying vehicles—but through Bharatanatyam. “I did the visuals,” he recalls, “and we started bringing in electronic music as well.”

But it was only in 2017, when Red Bull Music invited the three of them—Thiruda, his mother, and Murthovic—to reinterpret Antariksha Sanchar as a live dance show that the duo came together for their first meaningful collaboration.

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and the cancellation of a slew of scheduled shows led them to rewire their plans. While Antariksha Sanchar had been a start, its heritage-heavy storytelling and colonial-India setting seemed too heavy to sustain as their artistic vision going forward. Leaning into both their early club roots, the duo pitched Elsewhere in India as a speculative future project for another British Council grant. “And it got accepted,” share the men with the infectious glee of high-school boys. “The idea was a hybrid audio-visual experience—about a post-heritage India, set in 2079 AD, where people live in cultural amnesia,” clarifies Thiruda.

However, every story needs a narrative anchor of its own—a totemic, emotional core that would propel the story forward without ever drowning its primordial goals. This anchorage, for the men, was a no-brainer. Almost like MF Husain’s elusive muse Gaja Gamini, Thiruda and Muthovic began world-building for their Indo-futuristic vision by coming up with the fable of Meenakshi, a cultural cyborg of a dancer-singer polymath, modelled on Thiruda’s mother. “The idea is that we’ve formed a kind of band and are travelling across India salvaging bits of heritage—musical instruments, folklore, memories—and reimagining them as a new cultural experience,” he explains.

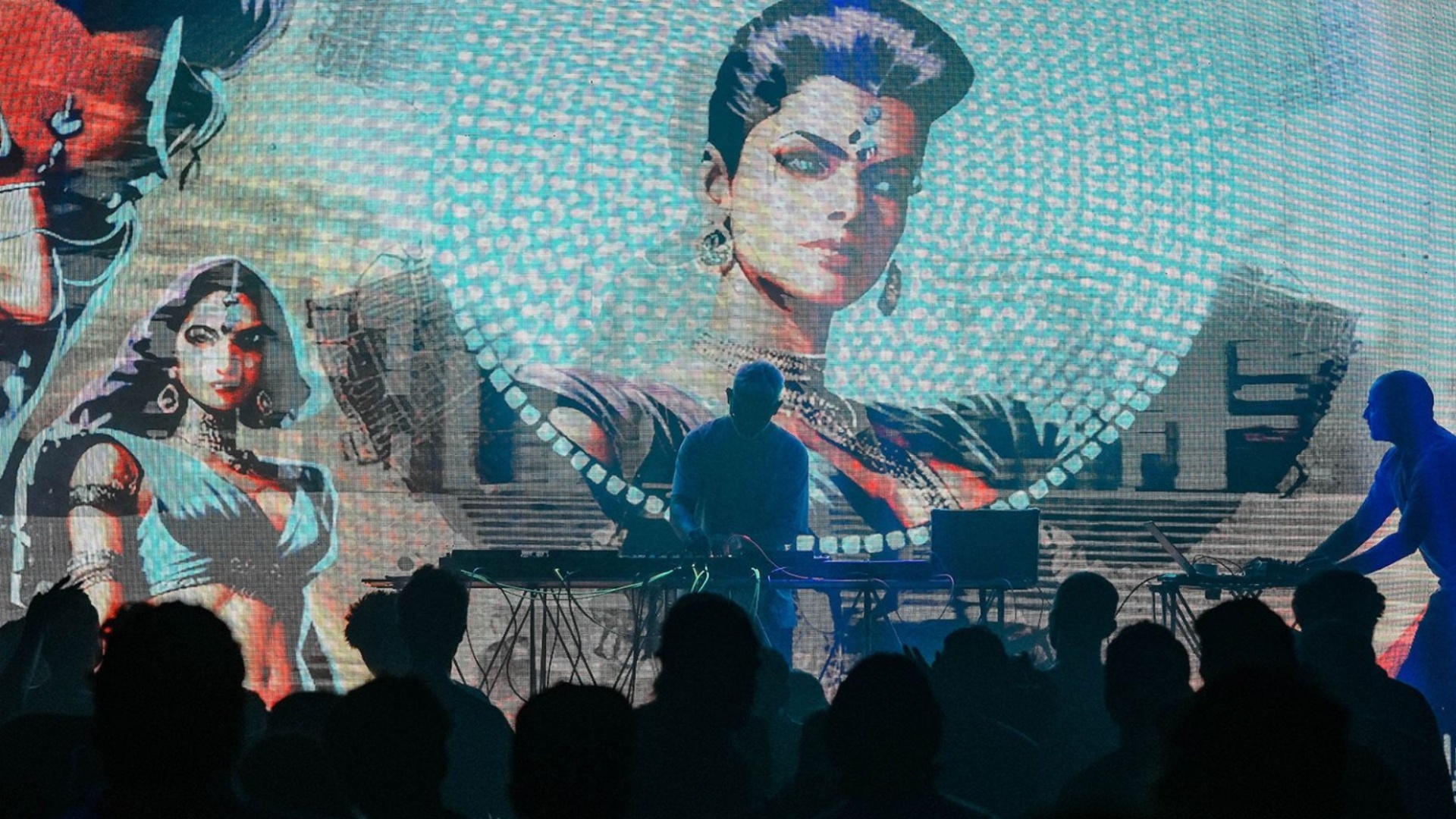

Buried under accessible layers of interactive art, post-punk beats, and heaps of visual storytelling, Elsewhere in India’s Barbican offering is a culmination of the duo’s continued exploration of post-cyberpunk instruments. In a futuristic world, they meditate on ideas of heritage, identity, and decolonial politics by re-imagining state-of-the-art instruments from the subcontinent.

“For Barbican, we selected the harmonium and sarod to show how Indian music is essentially global in origin,” says Thiruda before launching into the most fascinating history lesson of the harmonium’s Austrian and the sarod’s Persian roots. “In 1940, the harmonium was banned for decades on All India Radio, but now it’s a core part of Hindustani classical,” he explains.

The duo tirelessly worked with craftspeople near Kolkata to construct their hybrid renditions of these now-classical instruments by adding old electronic parts—salvaged from ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s devices—to create a mutated avatar of these instruments. These modified art installation/instruments, Murthovic explains, don’t produce sound. “But, with their modern reconstructions, engineering upgrades, and designs, they represent a heritage-driven dubstep or electro-classical dance music,” he says after a pause.