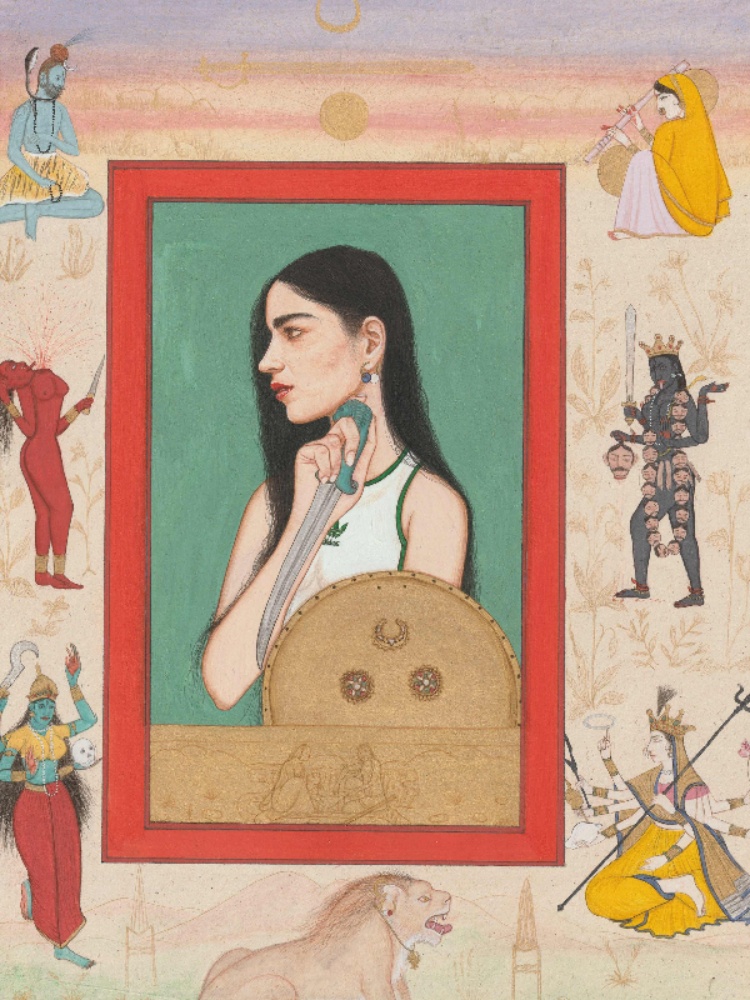

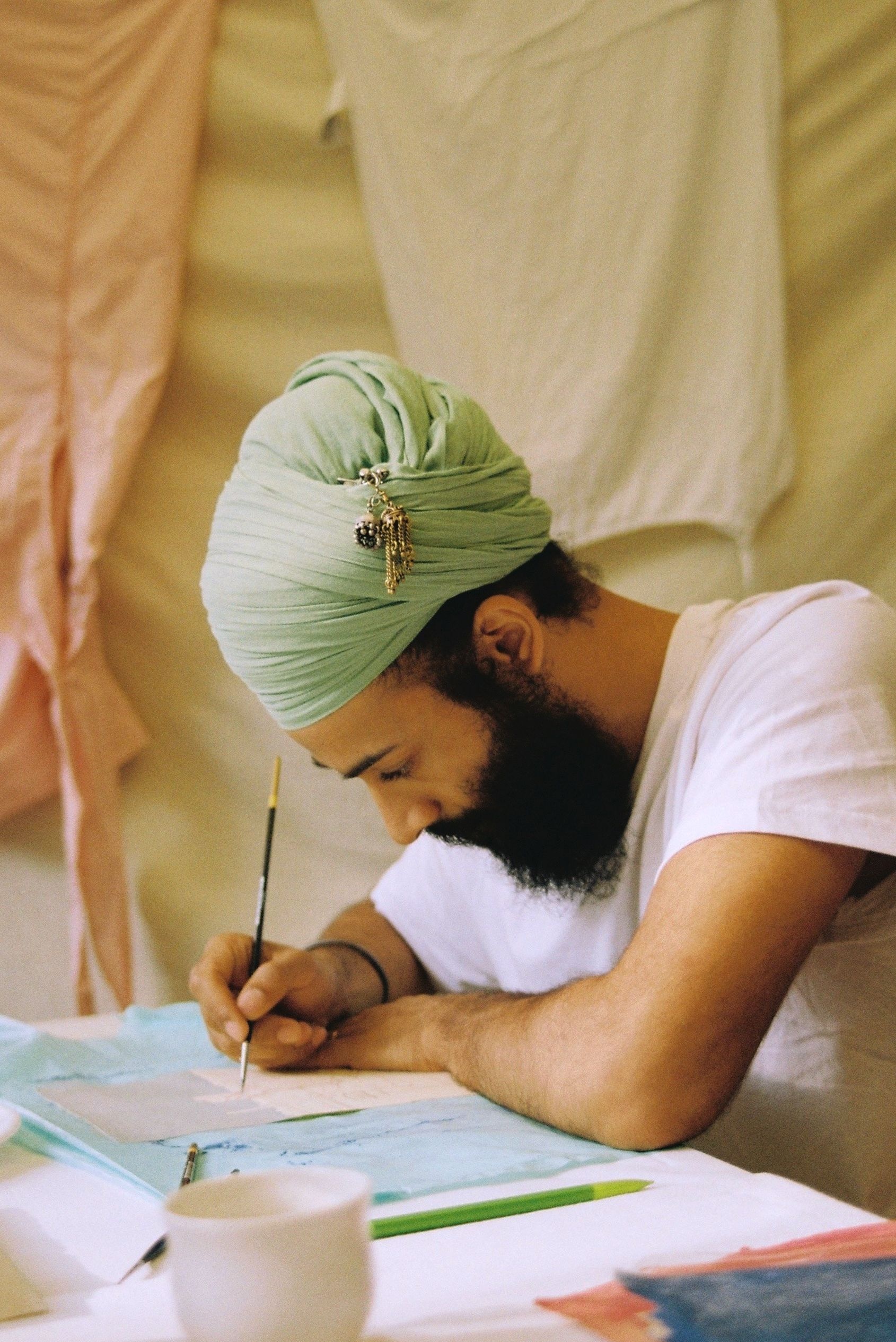

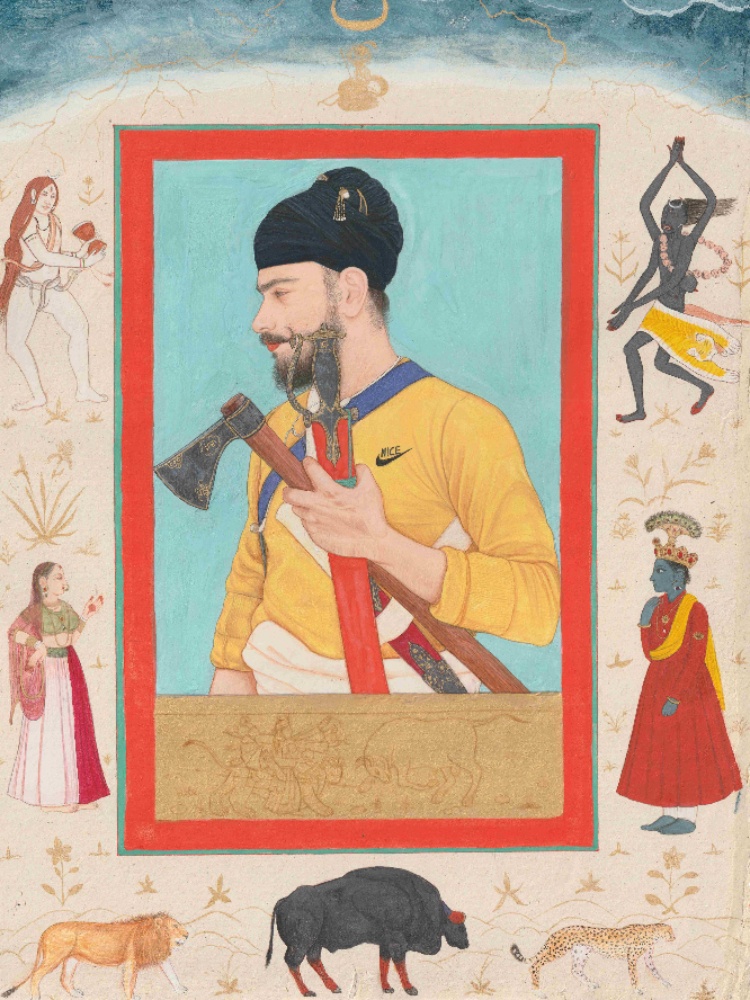

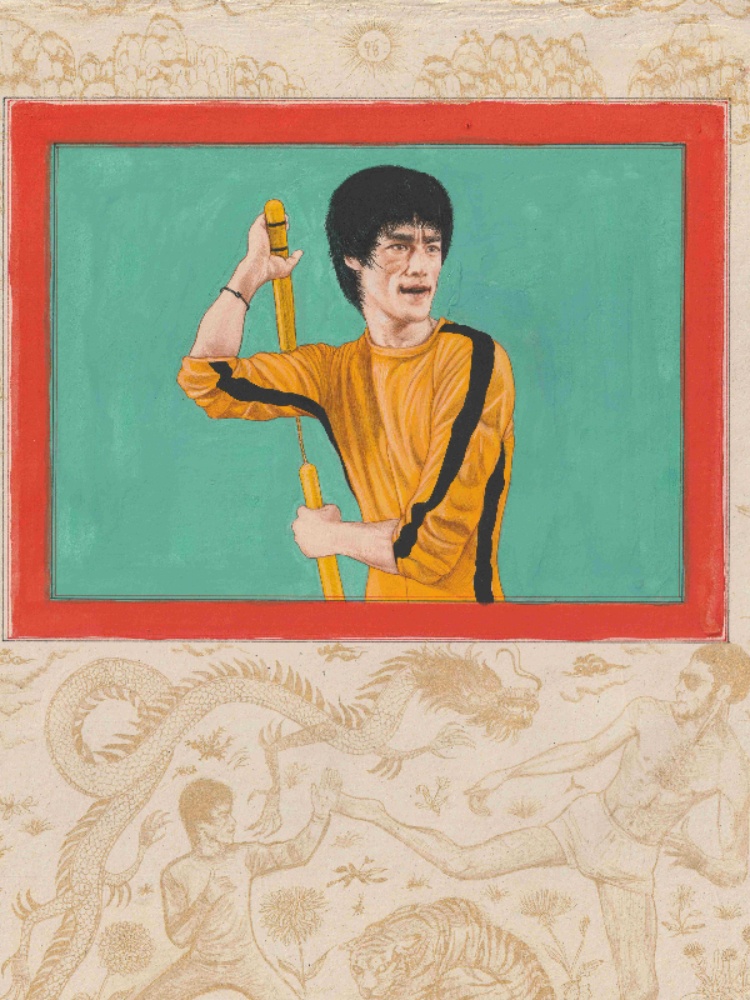

“Meet Lemon Singh,” announces London-based artist-musician Jatinder Singh Durhailay, pointing to his rescued pet canary chirping away in the background. Located in the quiet solitude of Oxfordshire, the Sikh artist’s studio is a colourful space filled with stories that bridge the old and the new. The 36-year-old has managed to carve a niche for himself by reimagining the miniature painting tradition. Currently making waves at Drawing Now Paris with Purdy Hicks Gallery, he was also at Art Singapore with Anant Art Gallery in January.

In more than one way, Lemon Singh, found almost frozen on the streets of Oxfordshire, mirrors the artist’s core ethos—a harmony of nurture, resilience, and colour. His name, inspired by his bright yellow plumage, ties into Durhailay’s own love for the colour. “Yellow strikes a chord with me. It’s peace and contentment. My love for it stems from Van Gogh’s ‘Sunflowers’ and raga Kalyan, a melody that feels yellow to me,” he shares.

Despite growing up in Leytonstone, East London, in a part of the city synonymous with punk-rock enthusiasts, rebellious graffiti art, and gender-bending sartorial silhouettes, Durhailay’s childhood was steeped in Sikh teachings and the vibrant rhythms of prayer. At home, there was no fence dividing his garden from his Jain neighbours’—an open space symbolic of shared values and cultural exchange. “We’d watch episodes of Mahabharata and Ramayana together on borrowed VHS tapes. Those stories stayed with me, shaping my fascination with characters and heroes,” he recalls. In many ways, he is a thorough London boy to the core—just one who didn’t join his mates for that Friday-night pint of Guinness at the local pub. “Friday nights were reserved for me to learn the dilruba, which I was fascinated with,” he says of his bowed instrument. “It was who I am, and I loved doing it.”