Some cities are inherited not through family but through flavour. I grew up in Kolkata, where the ghost of Lucknow lingers in every plate of Mughlai food. The slow, sealed patience of dum biryani, the smoke of meat on coal, and the faint whiff of kewra, all carry the memory of Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Awadh, who brought his cooks and their recipes with him when he was exiled to Metiabruz in the 1850s.

In a way, I’d been chasing Lucknow long before I set foot there. I’ve eaten at Manzilat’s, run by the Nawab’s great-great-granddaughter, who keeps those old Awadhi recipes alive in her Kolkata home. The biryani is perfumed with restraint; the kebabs melt into sighs.

So, when UNESCO named Lucknow a ‘Creative City of Gastronomy’ this month, it felt less like a new title and more like the world finally catching up. In August, my wife and I had planned a three-day trip, with an itinerary built entirely around food—each meal a way of understanding the city. We scoured the internet for online suggestions and took notes from local friends. Our trip wasn’t about chasing starched-tablecloth restaurants but the kind of places where the food still tells its own story—no frills, no pretence. Here’s our tried-and-tested hitlist.

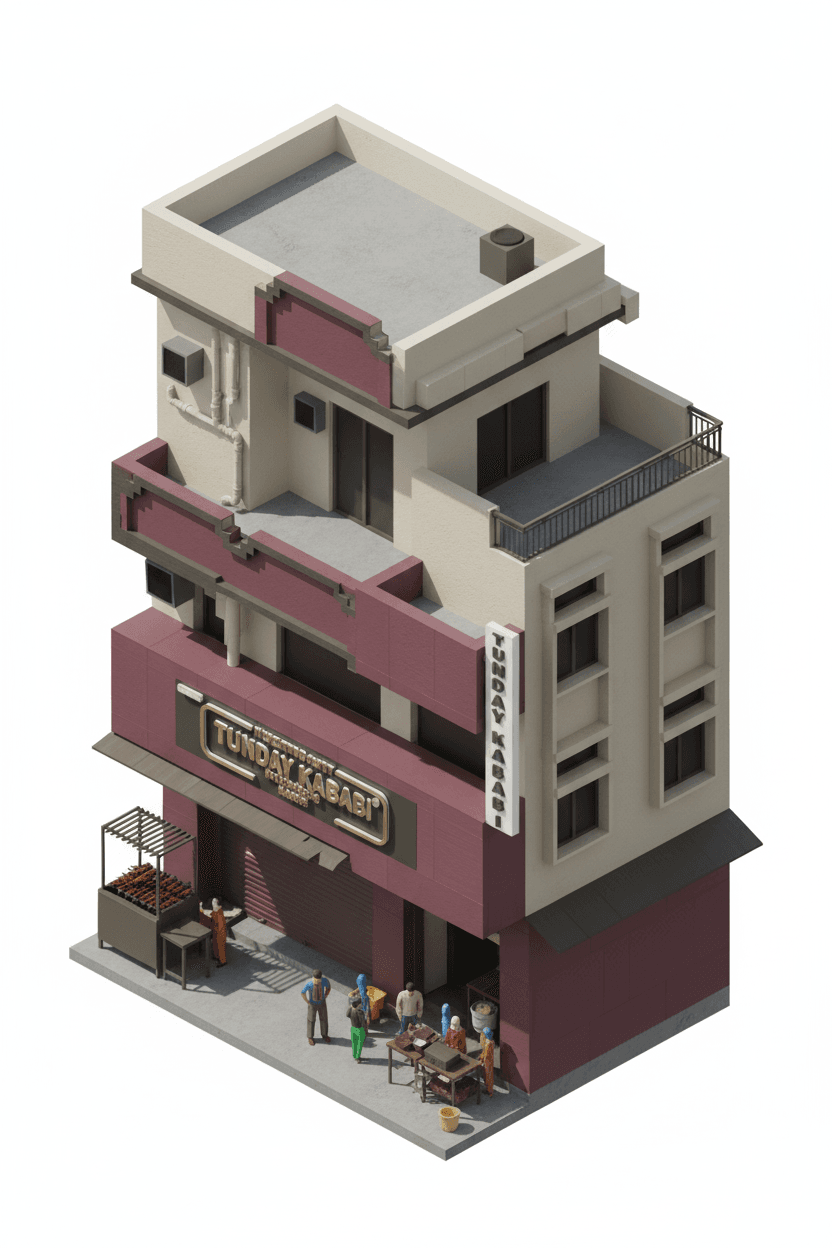

1. Tunday Kababi, Aminabad

We began, as everyone must, at Tunday Kababi. Its story is stitched into Lucknow’s culinary folklore. Founder Haji Murad Ali lost an arm in an accident but went on to create kababs so soft they could be eaten without teeth. Legend says Nawab Asaf-Ud-Daula, robbed of his molars but not his appetite, had thrown open a challenge to every cook in Awadh: make the most tender kababs and earn royal patronage. Murad Ali’s one-handed mastery won the contest—and the Nawab’s heart. More than a century later, his family still guards that recipe, said to hold 160 spices, in the smoky lanes of Chowk where it all began.

We half-expected the touristy hype to hide an underwhelming reality. But there’s something about watching the galawati kebabs being made that shuts down all cynicism. The cook’s hands move with hypnotic precision, shaping delicate rounds of minced meat on his palm as he presses them gently onto the sizzling pan.

Our kebabs and ulte tawe ka paratha arrived on modest white melamine plates. What strikes you immediately about the kebab is its texture, or rather the absence of it. The meat, finely minced buffalo or mutton, is worked until it’s almost a paste, then mixed with hand-ground spices. Melt-in-the-mouth barely covers it. It yields instantly, collapsing into a silken paste that coats your tongue. The smoke and ghee, the cardamom’s sweetness, a trace of mace, the warmth of black pepper and cinnamon, and the floral lift of kewra announce themselves in waves. A faint note of acidity cuts through the richness in the kebab and keeps it from being cloying.

The warm and pliant paratha comes pocked with air bubbles that have charred and browned. Soft enough to fold without tearing, it steadies the galawati’s collapse with its faint chew and is the perfect accompaniment. For good measure, I tried a sheermal too, its surface tinted orange from saffron and glistening with a light sheen of ghee. Each bite released the flavour of cardamom and milk, its faint sweetness offering a different kind of balance to the kebab.

I left with the overriding impression that what you taste at Tunday is skill more than spice, the kind of control that comes only from a kitchen where recipes are guarded secrets and techniques are passed down.

2. Raheem’s Kulcha Nahari, Chowk

The next day, undaunted by the swelling morning crowd in the market area, we found ourselves at Raheem’s Kulcha Nahari. Tucked in a basement in the congested by-lanes of Chowk, Raheem’s has been here for over a century, founded by Haji Abdul Ghani and named after his son, who perfected the ghilaf kulcha. Passed down through four generations, the nihari still follows the old rhythm. The meat—buffalo or mutton—is cooked overnight on wood fire in copper pots, spices tied in muslin and lowered into the simmering gravy.

When the shallow steel bowl of nihari arrives, it looks almost medicinal—a deep rust-red stew glistening with globules of fat and studded with chunks of shank meat so tender they collapse at the gentlest prod. The first taste hits like a revelation. You taste the woody depth of slow-cooked bone, and a complexity that speaks of cumin, cloves, fennel, cardamom, and nutmeg. The marrow lends an unctuous richness. Each bite is lifted by the brightness of fresh ginger juliennes and chopped green chillies that cuts through the heartiness, leaving behind the slow burn of spices.

But the two-layered ghilaf kulcha (ghilaf meaning ‘cover’) is the bridge that makes sense of it all and is the real highlight. The top layer is worked with ghee and milk to give it that soft sheen, while the base is leavened with yeast so it puffs up gently over the heat, creating that perfect balance of crisp outside and tender inside. You tear into it with both hands and drag it through the nihari until the bread is soaked burgundy. The combination is elemental. The kulcha’s slight sweetness tempers the nihari’s almost feral intensity. It’s the kind of serious food that demands silence.

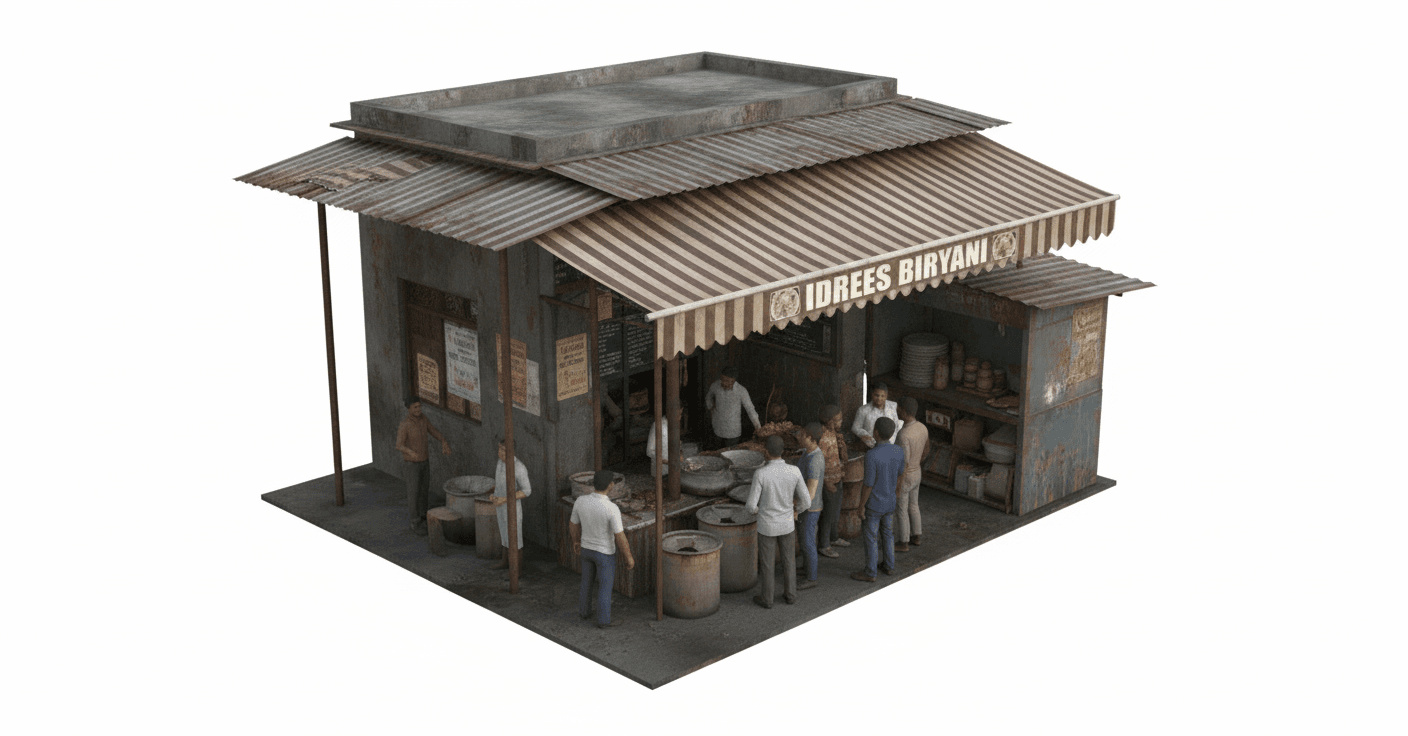

3. Idrees Biryani, Jauhari Mohallah

For lunch, we zeroed in on Idrees Biryani, which sits on a chaotic corner of Chowk, its open kitchen spilling smoke and the smell of slow-cooked goat meat and brown onions into the air. Established nearly a century ago, it’s still run by the descendants of the man who first began serving biryani to workers and traders after dusk. Nothing here tries to impress. It looks more like a working kitchen than a restaurant. Large degs (cooking pots) bubble away on chullahs or rest on benches outside. The ground is slick, and men dart around quickly between the pots, tending to the fires, checking the heat, or stirring the meat that will go into the biryani. On one side, there’s a cramped room with a single table, where men eat in silence. It’s raw, busy, unapologetically functional, and completely devoted to the one thing that matters—their much-talked-about biryani.

The man taking orders on the road sized us up and decided we weren’t built for the place. He gave us that faintly amused look locals reserve for outsiders trying too hard. He gently suggested we pack the food instead. We didn’t protest.

Back in our hotel room, the magic had dulled a little. The biryani was still fragrant, but the steam that once carried its spirit had long escaped the paper boxes. The long-grain rice had lost that loose, airy texture. The pieces of meat no longer glistened with heat. Though, you could still taste the richness—the meat slow-cooked in milk, cream, and a careful blend of spices, then layered with rice and sealed in a deg to finish under dum. It reminded me of a yakhni pulao, where every grain is steeped in the stock’s quiet strength. It was still soulful food, just no longer alive with the heat. This biryani wasn’t meant for hotel rooms. It was meant to be eaten where it was born, in the thick of noise, smoke, and devotion.

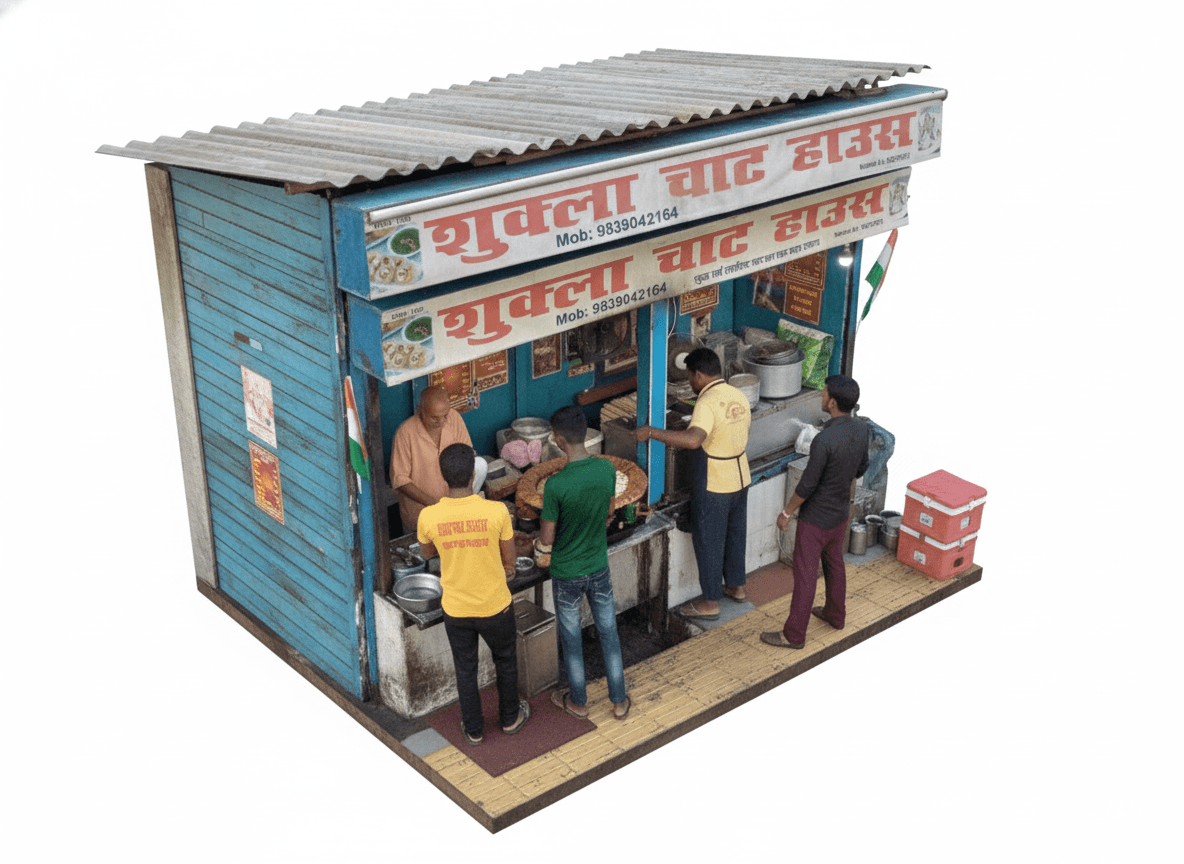

4. Shukla Chaat House, Hazratganj

Evening rolled in and common sense said stop. We headed straight to Shukla Chaat House. Tucked inside Hazratganj, it’s the sort of place you could walk past without noticing if it weren’t for the crowd spilling onto the street. Lucknow takes its chaat seriously, so for a stall to stay relevant here for over five decades says something.

A huge iron tava dominates the stall, covered with patties arranged in concentric circles. They sizzle under the watchful eye of an elderly man who looks like he’s been manning that skillet forever, calmly assembling plate after plate as his helpers call out orders. Around him, leaf bowls are lined up like a production line, waiting for their turn to be filled with either matar chaat, aloo tikki, or paani ke batashe (pani puri in Mumbai, golgappas in Delhi).

The paani ke batashe are thin, crisp, and refreshing, but didn’t quite hit the fiery, tangy note. I still lean toward the spicier, punchier phuchkas of Kolkata.

The aloo tikki felt familiar yet different. No dal filling here, just potato through and through, fried till crisp on the outside and soft within. Two tikkis are hand-broken into a bowl, drowned in cool yoghurt and tamarind chutney and topped with fresh coriander and crushed batashe. Each bite balances heat, creaminess, and crunch, the kind of combination that makes you forget how much you’ve already eaten.

The real draw is the matar ki chaat—boiled white peas, roughly mashed, then hit with a riot of spices, lime juice, fresh coriander, and crushed batashe for crunch. A friend had tipped us off to order it with just a sprinkle of ginger and nothing else, to taste it the way the initiated prefer, without the distraction of chutneys. The result is thick, spicy, and bright with tang. By the end, you’re full, happy, and slightly dazed that something so simple can taste this layered.

5. Ram Asrey, Hazratganj

The next morning, at Azrak, the signature restaurant at the Saraca Hotel where we were staying, a leisurely breakfast set the tone for the day’s indulgence. We sampled the ‘galawati benedict’, a modern play on the traditional kebab, and followed it with the khasta puri, crisp and delicate, quintessentially and unpretentiously Lucknow. Later, lunch was Azrak’s Awadhi dum gosht parda biryani, a dish of remarkable subtlety and balance, each grain infused with gentle aromatics, and one of the most exquisite biryanis I’ve had and impossible not to recommend.

After the savoury rhythm of our previous meals, we were ready to shift gears and follow a sweeter tempo, exploring some of Lucknow’s most celebrated confections.

At Ram Asrey, established in 1805, we ordered the malai paan gillauri, which arrives shaped like a folded betel leaf—a triangular wedge of pale cream that has been moulded into the recognisable shape of a betel leaf paan. The origin story, as the shop tells it, involves Nawab Wajid Ali Shah’s well-wishers approaching Ram Asrey with a request to create something that might replace the Nawab's paan and tobacco habit. The confectioners’ solution was literal mimicry: a sweet that looked like paan, folded like paan, was meant to be eaten in one bite like paan, but constructed entirely from malai sheets that require hours of careful milk reduction to achieve the proper pliable texture. The top is finished with silver leaf. Inside, the filling provides textural contrast from the pistachios, almonds, cashews, and mishri, but it’s the cream that dominates. What’s remarkable, though, is how un-sweet it is, or rather how the sweetness operates at a level that feels almost restrained given the category.

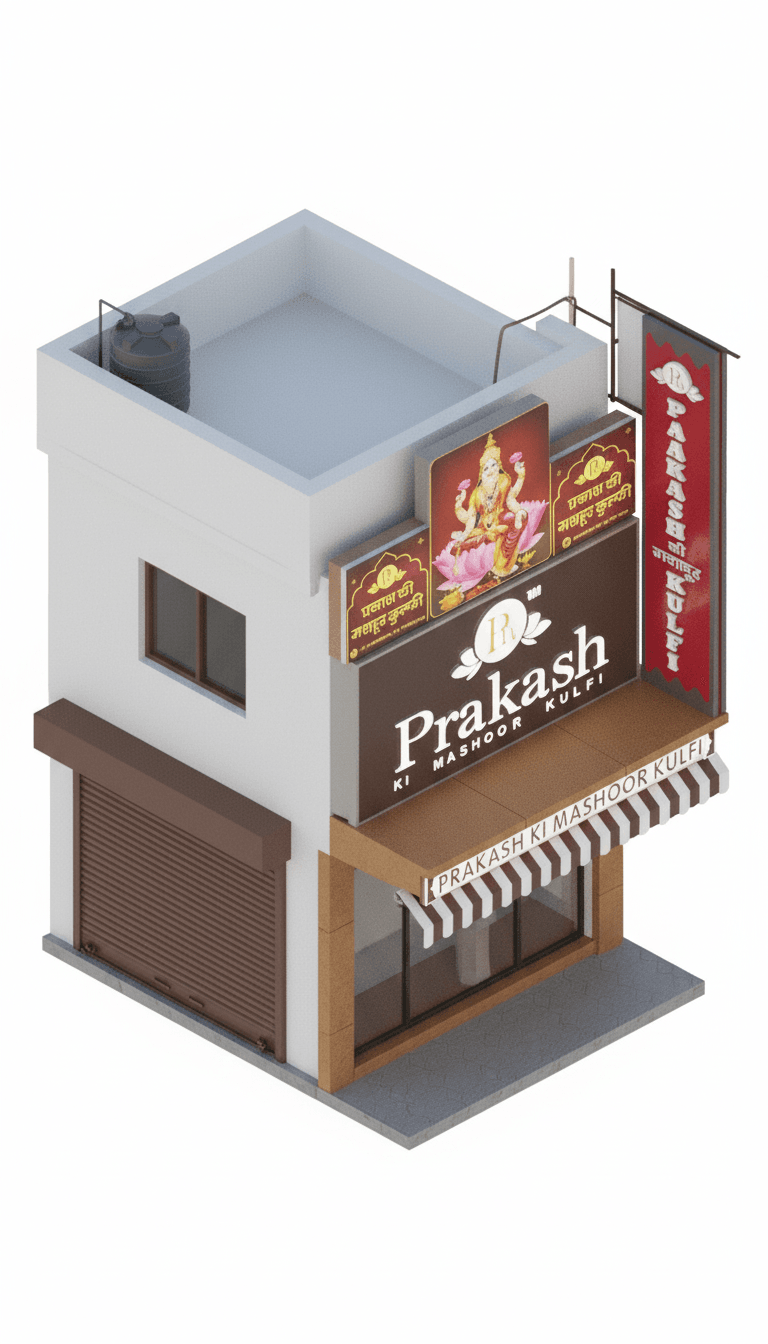

6. Prakash ki Mashoor Kulfi, Aminabad

Next on our list was Prakash ki Mashoor Kulfi, a landmark in Aminabad since 1956. Their kesariya badam pista kulfi is dense, tasting of nuts, cardamom, and saffron-infused milk frozen into silken smoothness. It operates in a similar register: sweet, yes, but more about the depth of the reduced milk and the comfort of something smooth and cold. Each bite, complemented by the delicate falooda, is intensely satisfying. Part of the charm here is the old-school ritual at the counter. You’re handed a small metal token, a disc with a hole in the centre and a number and the restaurant’s name engraved around it. It’s a promise of your order, which you hand over to the waiter when your kulfi is ready—a simple, tactile tradition that has endured alongside the decades of kulfi-making.

7. Bajpayee Kachori Bhandar, Hazratganj

By early evening, we were hungry for a snack, and our attention turned to Bajpayee Kachori Bhandar. When we reached the stall—little more than a hole in the wall—customers jostled around their parked two-wheelers or stood at a few steel tables, some waiting for their golden prize, others using their scooter seats as makeshift tables to tuck in. Inside, a man sat cross-legged at counter level, flattening dough balls and flicking them through the air into a blackened kadhai bubbling away up front.

When it’s your turn, you watch the puri kachoris being fried. They emerge blistered and golden, smoke curling up around them, the light, crisp shell promising immediate crunch. They’re served with a spicy aloo-chholey sabzi that hits hard with bold, robust flavours and a lingering heat from black pepper and green chilli. Every bite is a study in contrasts: the impossibly crisp outer shell of the puri offering crunch, the sabzi soft and punchy.

The experience is marked by the pace of service and the shared rhythm of everyone around you, standing, biting, nodding. Whether you grab a portion on the fly or linger for a few minutes letting the flavours settle, it’s clear that you’re tasting a slice of the city’s everyday pulse.

We left Lucknow the next morning, the city already stirring to its familiar rhythm. The same rituals had begun again, as they must have for decades, unchanged, unhurried, perfect in their repetition. Somewhere, dough was being rolled, oil was heating, and the day was taking shape much like the one before it.