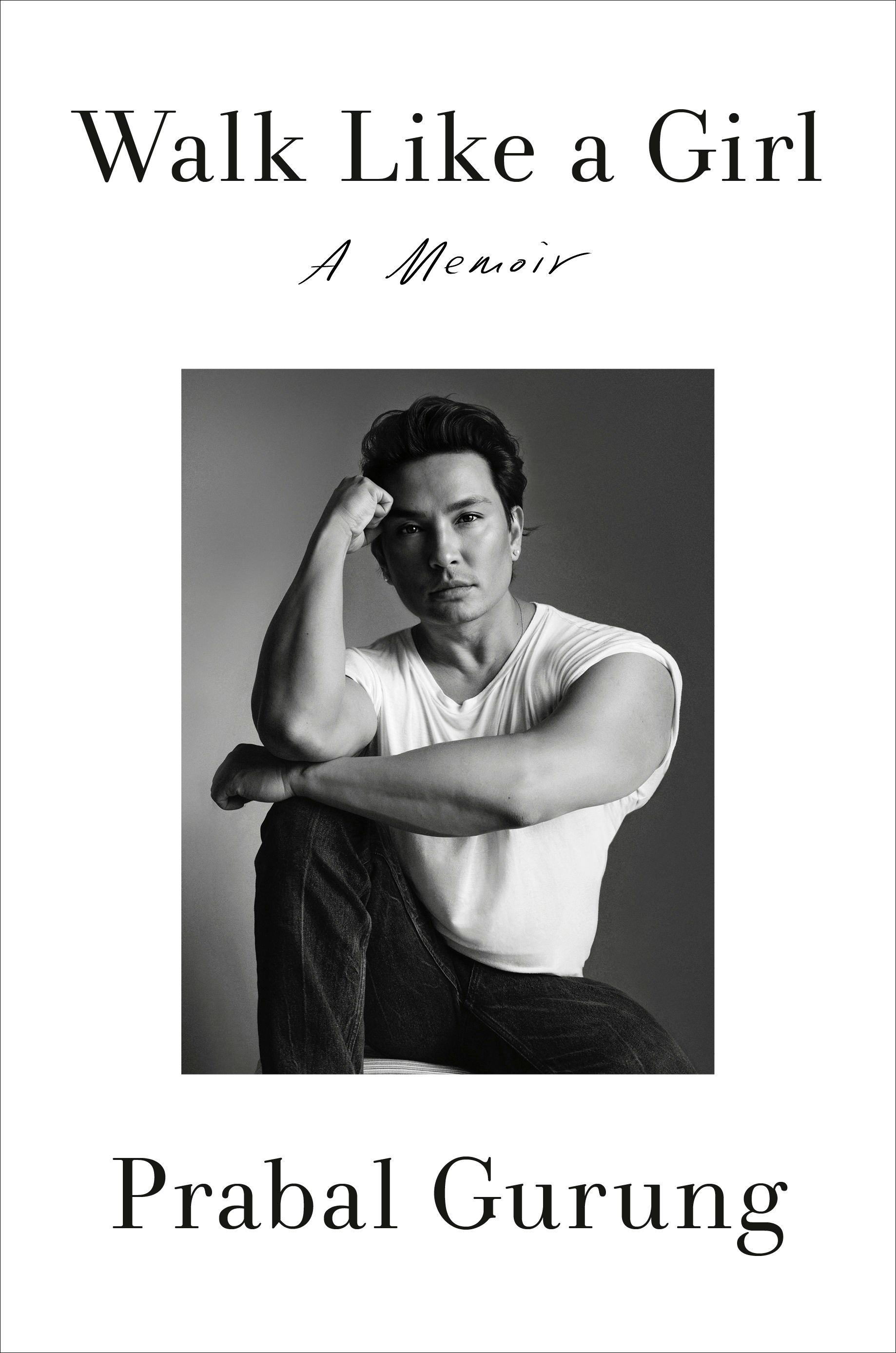

Prabal Gurung is a fashion designer, but he’s also so much more. He’s a feminist. An activist. A political campaigner. A jewellery designer. A man who knows all the lyrics to ‘Ajeeb Dastan Hai Yeh’ and can recite the poems of Rudyard Kipling. All of this and much more is evident from the designer’s new memoir, Walk Like a Girl, published by Viking, which releases today.

The book offers a chronological glimpse of Gurung’s journey and, ultimately, his search for inclusion. It follows him from misfit schoolboy in Kathmandu, Nepal, where he was mocked for his femininity, to his time studying at NIFT-Delhi, where he was coming to terms with his sexuality, to the time he worked with Manish Arora. He doesn’t gloss over the infuriating racism he faced while studying at Parsons School of Design in New York or while rising the ranks at Bill Blass, where he was design director for five years. He acknowledges the friends who helped him build his independent label in 2009 and the thrill of dressing women like Zoe Saldana, Michelle Obama, and Oprah.

All of these experiences leak into his collections, where, through colour, print, and cut, he detangles what it means to be an American—a proud New Yorker, yes, but also an equally proud immigrant. One who is vocal about the causes that are close to his heart, be it fundraising for earthquake relief, sending out slogan T-shirts supporting the #MeToo movement, or even campaigning for Hillary Clinton.

But when you’re doing all that, how long does it take to write a book of your own? Especially one that’s so cathartic, filled with moments of rage and joy all at once. “It’s taken me almost six years to bring these decades of stories to fruition—years of courage, self-belief, perhaps some delusions, manifestations, and many individual faiths,” he writes towards the end.

Ahead, the designer spoke exclusively to The Nod about his writing process, literary inspirations, and that Diljit Dosanjh Met Gala look.

The book is almost a love letter to New York. What’s your favourite spot in the city?

There’s a little bench in Washington Square Park. I go there when I need to remember who I am. The skyline reminds me to dream. The trees remind me to stay grounded. It’s one of the few places in the world where I can feel anonymous and infinite all at once.

What are the authors or books you had by your side while writing?

Gloria Steinem taught me that personal truth can be political. Arundhati Roy showed me that beauty can carry revolution. James Baldwin sat beside me the whole time—his courage, his clarity. Edward Said reminded me of the responsibility that comes with perspective—of what it means to love a place and still interrogate its power. Never Let Me Go stayed with me like a quiet ache. Ocean Vuong made me believe in the poetry of fracture. Sally Rooney reminded me that intimacy is its own kind of protest. And Hernan Diaz’s Trust—so exquisitely layered—made me think about truth, power, and who gets to tell the story. These weren’t just books; they were mirrors, provocations, and lifelines.

How did you make time to write while running your label?

It wasn’t glamorous. It was 5 am writing sessions, scribbles in between fittings, voice notes during cab rides. I didn’t wait for inspiration—I built a discipline around truth-telling. Some mornings the words came easily. Other days, they had to be carved out. But I showed up.

The second half of the book covers a lot of your advocacy work. You co-founded Shikshya Foundation Nepal with your siblings to help educate underprivileged children. You’ve spoken up during the #MeToo movement, raised funds for Times Up and Planned Parenthood. How do fashion and advocacy overlap for you?

Fashion, for me, has never been just about clothes. It’s always been a language—a way of saying ‘I see you. You belong. You are powerful’. Advocacy and fashion both begin with a belief in transformation—of the self, of the world. When a woman wears something that makes her feel like she owns the room, that’s political. When a garment tells a story of identity, resilience, and history, that’s activism stitched in silk.

Tell us about that iconic Diljit Dosanjh look.

It was more than a look—it was a moment. A prayer in motion. I’ve spent my whole life dreaming of what it would mean to see someone who looked like us, dressed like us, being celebrated, not just accepted, on one of fashion’s grandest stages…

We didn’t want to dilute tradition—we wanted to elevate it. The sherwani, the cape, the embroidery with the messages, the layered silks… Every detail was a love letter to the ancestry and a bold declaration. Saying ‘we belong here’ without apology.

We worked across time zones, sent hundreds of WhatsApp messages, voice notes. But through it all, the intention never wavered: we were doing this for the boy in Punjab who thinks fashion is not for him. For the uncle in Jackson Heights who wears his turban with pride. For every South Asian who has felt invisible in rooms of power and beauty. And I hope—I truly hope—I did the country, our culture, and our continent proud.

What’s on your calendar for the rest of the year?

A global book tour, new collections, and—hopefully—quiet moments of joy in between. Time spent with my mami. I’m also working on a screenplay and laying the foundation for a larger platform that connects creativity with consciousness. The goal is always the same: to leave the world more beautiful than I found it.

Prabal’s hot takes:

Matcha lattes: A mood. But only if someone else makes it.

Skinny jeans: Let them rest. They’ve done enough.

Beauty injectables: Your body, your rules. Just don’t erase what makes you you.

The Pitt: Brad? A dream boat :-)

JK Rowling on Twitter: The pen was mightier. The tweets? Not so much.

Ahead, read an excerpt from Walk Like a Girl by Prabal Gurung

American high society reminded me of high society in India and Nepal in terms of wealth and class—the only marked difference was skin colour and the type of gowns women wore. But what struck me was how myopic Americans were—they knew very little of the world beyond the United States and Europe, whereas the people I met in Asia’s upper echelons were extremely cosmopolitan. The other thing I found fascinating was that for all this talk of feminism in America, these high-society women were as trapped by the patriarchy as those in Nepal and India. There was a stunning hypocrisy—this idea of independence felt like an American marketing ruse.

I was always one of the very few people of colour at any of these events—and fully aware that my access was simply because of my position at Bill Blass and that two of my dearest friends—Barbara Bush and Maggie Betts—were also clients. Barbara had introduced me to Maggie, and we immediately hit it off. She was confident and cool, and one of the very few biracial woman I’d ever seen in high society. Her father, Roland Betts, was friends with George W. Bush, which was how she knew Barbara, and her mother, Lois, was one of the few Black socialites on the scene back then. Maggie invited me to dinner at a French restaurant on Lafayette Street, and on that first date, we became fast friends.

Bill Blass often sponsored tickets to galas, so I’d dress Barbara and Maggie and take them as my dates. For the Guggenheim gala one year, I dressed Barbara in a sparkly black dress and Maggie in a stunning black tuxedo. Robert Jonathan Barnes, a pseudo-socialite I knew from my Parsons days, was also there. When he saw me with my stunning dates, he said, “What are you doing here?” in a snide, surprised way.

“Maggie and Barbara invited me,” I said, annoyed by his disdain, but not surprised. I never liked him.

But then Maggie corrected me. “That’s not true!” she countered. “Prabal invited us! We are his dates.”

I appreciated her sticking up for me, but Robert’s comment flung me back to his twenty-first birthday, five years prior. A few of my Parsons friends had been invited to his party on the Upper West Side, so I tagged along. Barbara and Maggie were both there, though we had also not yet met, as was Jessie Silverstone, a Black socialite who had been adopted by a wealthy white family. Someone had put together a video montage for Robert where everyone was saying something about him for his birthday. I can’t remember what Jessie had said in her tribute, only that Robert did not like it, as he stood up and yelled, “You fucking n——!”

I was stunned and immediately looked at Jessie—who was even more taken aback. But then I scanned the mostly white room and realized that no one else seemed to notice. Or, if they did, they didn’t seem bothered. That was even more terrifying than the comment itself. I saw the hurt in Jessie’s eyes and was about to say something but felt one of the friends that I’d come to the party with tug my hand—he was shaking his head no. I looked over at Jessie and saw that she kept quiet, too, as if it didn’t happen. It was eerie.

I turned to my friend and said, “I have to go.”

It was disturbing. But it was in line with the racism I encountered in these lily-white spaces, where people would say things like, “You’re beautiful. I don’t even think of you as Asian.” Even more ridiculous was when whoever hurled the insult would follow it up with, “Oh, lighten up! You know I love Asians!” Or, “I love sushi!” Or, “I love Indian food!”

I cannot tell you how many times someone has said to me, “I’m normally not into Asians but you’re attractive.”

My response has always been, “Well, too bad I’m not into douchebags.”

The surprise that I’d see on their face made me realize how clueless they were. Utter obliviousness is the privilege of being the majority. Encountering this kind of racism was a shock to me, as I’d come to this country with this delusion that it was founded on freedom for all. This was the heyday of Condé Nast, the company responsible for Vogue, Glamour, WWD, and Vanity Fair, all of which had dedicated socialite pages and society reporters, as did Hearst’s Elle, Marie Claire, and Harper’s Bazaar. It was a white haze of glory, glamour, and skinny blonde “it” girls, all celebrated in these pages, which gave the impression that the only way to succeed in the fashion world was to celebrate the white, Waspy, Eurocentric ideas of beauty. As one of the few brown people in the haute couture, luxury fashion space, I was also in a unique, and awkward, position as I witnessed this world as an outsider.

Walk Like a Girl: A Memoir by Prabal Gurung, published by Viking, is available from May 13