Set in unified Korea, Silvia Park’s debut novel, Luminous, paints a dystopian future, one in which robots are an intrinsic part of society. The story follows three estranged siblings—a humanoid cop, Jun; robot designer Morgan; and, you guessed it, a robot named Yoyo, designed as an early prototype by the siblings’ father.

At a time when we, too, are ensnared in the pros and pitfalls of AI, where the gap between reality and dystopia seems to be shrinking at an alarming rate, where engineers are teaching robots choreography, and speaking masks can instantly translate Mandarin into English, Luminous seemed the ideal choice as the first pick for The Nod Book Club.

The novel paints a world of humans and robots and those in the middle, of ‘augmented restaurants’, police precincts with ‘Robot Crimes’ divisions, VR addiction, and botfights, with the added socio-political dimension of being set in a unified Korea. There’s world-building, yes, but also stories of warmth and connection.

A conversation with Park throws up some surprising (and some not-so-surprising) facts about the author. She thinks she’s a bad short-story writer. She doesn’t believe we are ready for the responsibility of AI (!). She is a huge Astro Boy fan. And she calls her books her ungrateful children. Ones she feeds with her time, energy and money, in the hope that eventually they will set their own course out in the world. As long as it lives its own life, and doesn’t die tragically on the side of the road, she’s happy.

Luminous is definitely out there in the world; talks are underway to develop it for television by Media Res (Pachinko and The Morning Show). The book was published in March 2025, but Silvia started writing it back in 2019, and a good chunk of the novel was written during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Over a video call from her parents’ home in Seoul, where she grew up and lives (when she’s not teaching Creative Writing to students at the University of Kansas in the United States), Park discusses sci-fi, inspirations, and publishing in the time of AI.

Excerpts from the conversation:

How did you come to write Luminous?

There are quite a few origin stories for this book. My dad is a professor of American Studies at a university in Korea, and he wrote this paper about a Hollywood film that had just come out, called I, Robot, starring Will Smith. It was a terrible film, but he wrote a paper on it, which I read a gazillion times.

How old were you at the time?

I think I was 15, in high school. The fact that years later I wrote a robot book... Surely that has to be the reason why. I can blame my dad.

Another reason is that I grew up watching Astro Boy, a Japanese manga series, and what stuck in my mind was the child robot. Since then, we’ve seen a lot of robots that look like adults, and they come in two forms. One is like the Terminator—they’re trying to kill us—and the other is the robot that is supposed to be like our lover or partner. But the robot that really got stuck in my head is a child robot.

Children are considered the perfect example of humanity. To have them as robots...

They’re also supposed to change constantly. Whenever you see a kid, you say “you've grown so much”. And I think the idea of seeing a child never ageing is inherently very creepy. But there’s something compelling about it too, because one of the reasons why we are so fascinated and afraid of robots is that we have this fear of being replaced by them.

How did you start writing this book?

I originally started writing short stories. But I call myself a bad short-story writer, because I use them to test out ideas for longer works. I wrote two short stories; they were both character exercises. The first one was about figuring out the relationship between Jun and Yoyo, and the second was about the relationship between Morgan and Stephen. The way those two stories connected was through a character who no longer exists in the book. Originally, I didn't envision Morgan as Jun's sister. I imagined a different character as Jun's sister.

In the acknowledgements, you mention that Luminous was supposed to be a children’s book.

I started with that first chapter where Ruijie meets Yoyo in the junkyard and then eventually other kids join them, and they’ve formed this group. That was a children’s book. It was supposed to be a lot happier and adventurous.

But when I asked myself: how did Yoyo end up in that junkyard? The history of it became much darker. That’s when I realised I had a lot of interest in the adult side of that story. Though, I do feel the children’s storyline is in some ways darker than the adult storyline.

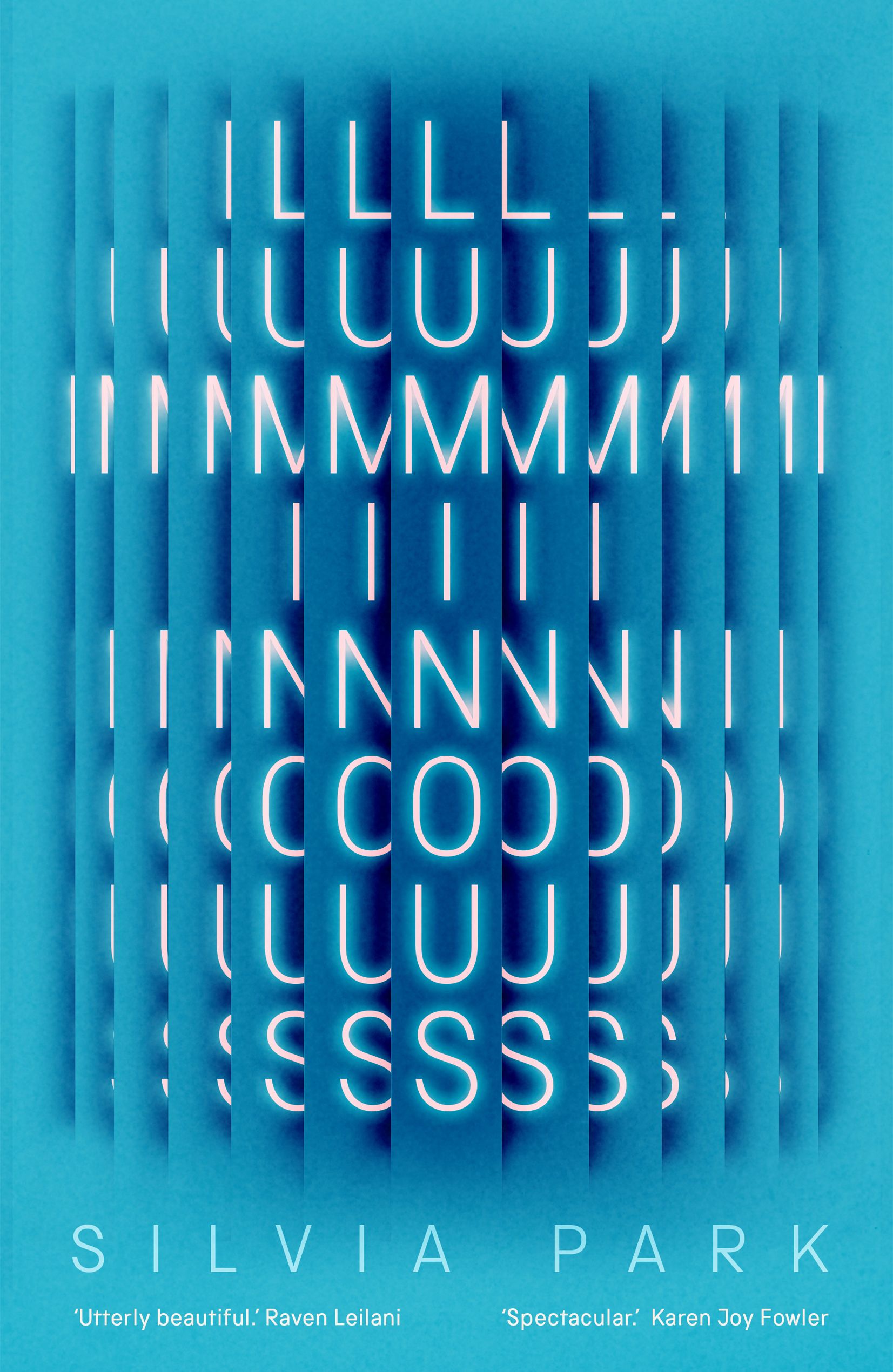

What’s the story behind the book cover?

I feel I didn’t get to talk to the designer, Jack Smyth, about it, but I got his intention. I remember when I first saw the cover, I was like, oh, so many Luminouses, there’s so many words. But then I thought, wait, that actually portrays my book pretty well. My book has a lot of layers; each reader will take something very different from it. I feel that the colour (of the cover) is representative of the book. When I look at that blue, I think of the virtual reality that Jun is immersed in.

What’s currently on your nightstand?

I am reading two things. A memoir by a killer-whale researcher called Into Great Silence [by Eva Saulitis]. The fiction that I’m reading is Susan Choi’s Trust Exercise.

Are there any authors you admire or anyone whose work has inspired you in any way?

Susanna Clarke, the author of Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell and Piranesi. What I really deeply admire is the way both works are very different. But her tone is very distinct, a sort of Jane Austenian tone, and yet both encapsulate her wonder with the world. She is fascinated by the world, but she’s fascinated about aspects of the world that I think people no longer really spend much time on or pay attention to. Ironically, my book is all about what people are talking about—artificial intelligence. That was not my intention. I didn’t intend Luminous to be timely. In fact, I think the fact that it’s timely is pretty depressing.

Why do you say that?

I don’t think we should be allowed to develop artificial intelligence. We haven’t figured out our own intelligence. We don’t know much about the brain; there’s so much more to discover about it. It’s going to be quite dangerous for us to now be focused on developing something that is meant to just replace us, because, really, what is the goal of artificial intelligence? It’s ultimately to replace us.

Do you foresee us living in a world with robots soon into the future?

In the past, I think if you had asked me this question when I was still working on the book, I would have been pretty sceptical. I would have said that I think the technology I portray in my book is fantastical, it’s really far off. But now with ChatGPT and LLMs I’ve realised it's not that. It’s not that I’m overestimating or underestimating how far AI will come. Rather, I realise I overestimated human intelligence.

I think as humans, we really want to be lazy, and we want things to be convenient, and we want things to cater to us. So, we are willing to allow ourselves to depend on technology.

What are your thoughts on AI and the publishing industry? Have you experimented with it in any way?

I have to admit I’m a complete noob with ChatGPT, which is very ironic. I was already finished with the book when ChatGPT started really kind of coming into the fray, so I didn’t really get a chance to use it. I think the last time I used ChatGPT was to write an e-mail, but that was a while back because I haven’t trained myself yet on how to use it, and that’s even putting aside a lot of the environmental costs of ChatGPT.

At this point I am quite concerned that AI promotes mediocrity. If the point of AI is to absorb as much of the work out there, then a lot of it is not going to be that great. PIus, if AI is producing what it most commonly sees, then surely it must be reproducing perhaps the most cliched and sort of stereotypical content.

What I also don’t understand is how AI is going to help our industry, whether it’s in publication or art or creative fields, because, really, our industry is not lacking in quantity. The bigger concern with a lot of entertainment industries is that there’s now too much choice. There are just too many shows to watch, and a number of them are not very good. They will be serviceable, or vaguely entertaining. But there’s only going to be a real few that are going to be diamonds. And I don’t think AI is going to be producing diamonds. In fact, AI will continue to produce a lot of coal.

What part of AI were you interested in investigating?

What I was particularly interested in is the most difficult aspect of replicating artificial intelligence, which is emotion.

We have convincingly started to develop artificial intelligence that could pretend to have emotions. But I was curious about whether it would ever be possible for us to invent an artificial form of emotion.

So that’s the rabbit hole I went down, because that taps into that question: what makes us different from them? Can we really argue that we are life and that they are not life? That we are alive and that they are not dead, but they’re not quite alive either? So that’s where the questions veer into sort of more abstract, less grounded in reality. It’s a lot of fun for science fiction writers to think about that, but it’s quite terrifying to imagine it happening in reality.