Shah Jahan would probably go into a seizure if he saw what we have done to the Taj Mahal, his beloved monument of love cast into eternity. I don’t mean the structure itself, but how, in the past 100-odd years, we have used it to sell everything from trinkets and knick-knacks and matchboxes and tea packs and hotels to anything that needs a veneer of second-hand glory. Somehow, the Taj has become the visual shorthand to evoke ‘India’, not love.

Like many Indians, I haven’t been to the monument since I was a child, because it’s just there, and one can go any time, and so one never really does. And because it is everywhere, it is kind of nowhere, and we have become blind to its charm.

So, on an ultra-polluted weekday, I entered the DAG exhibition The Mute Eloquence of the Taj Mahal, curated by historian-author Rana Safvi, in the hope that it would make me see the Taj in a new light. That it would return some awe and wonder dulled by over-exposure. That it would inject some emotion back into the monument that Tagore called “a teardrop on the cheek of time”.

It did.

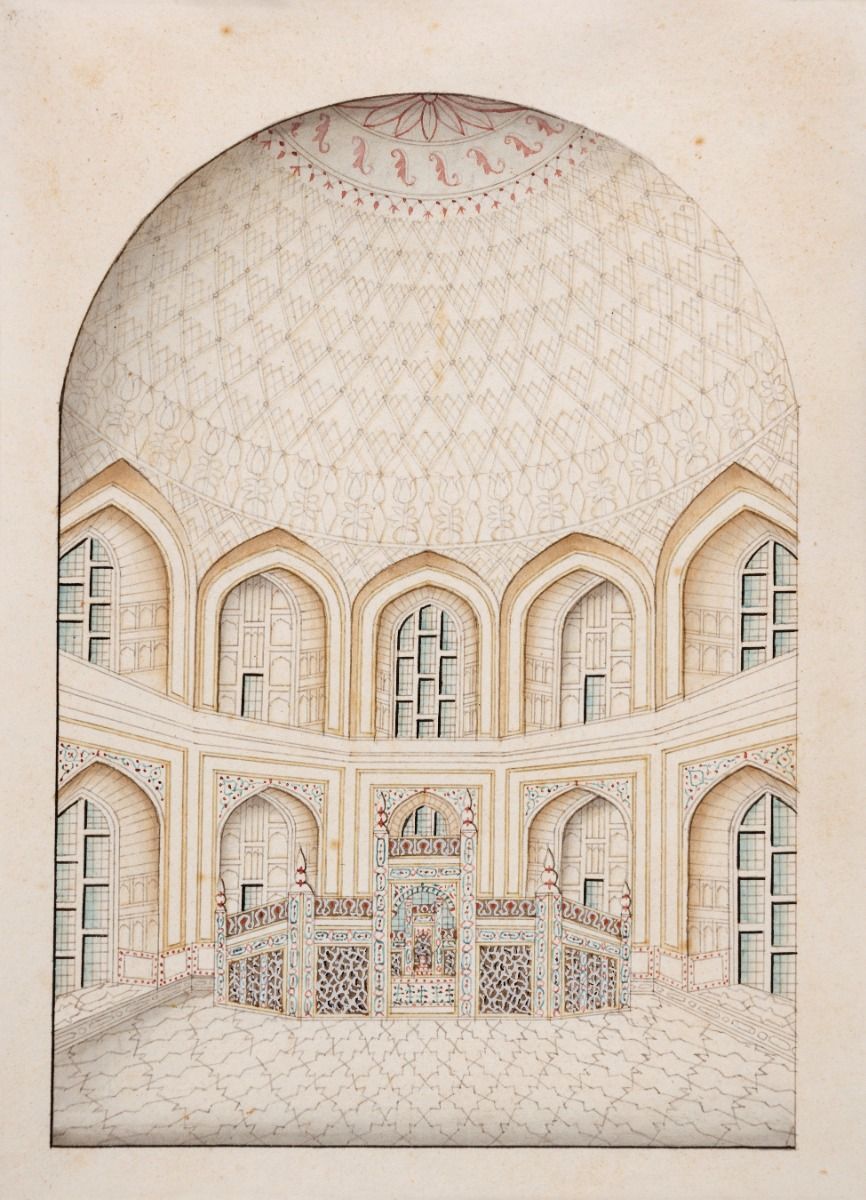

On display are over 200 intricate paintings, prints, photographs and plans—all from the gallery’s own collection—that take you inside, outside, and around the grand structure. You see the Taj in many settings and modes: in isolation; next to the Yamuna; tantalisingly far away; aesthetically blocked by a tree; a single minaret carefully framed; and even as Japanese prints. It’s the sort of details that you will miss in real life.

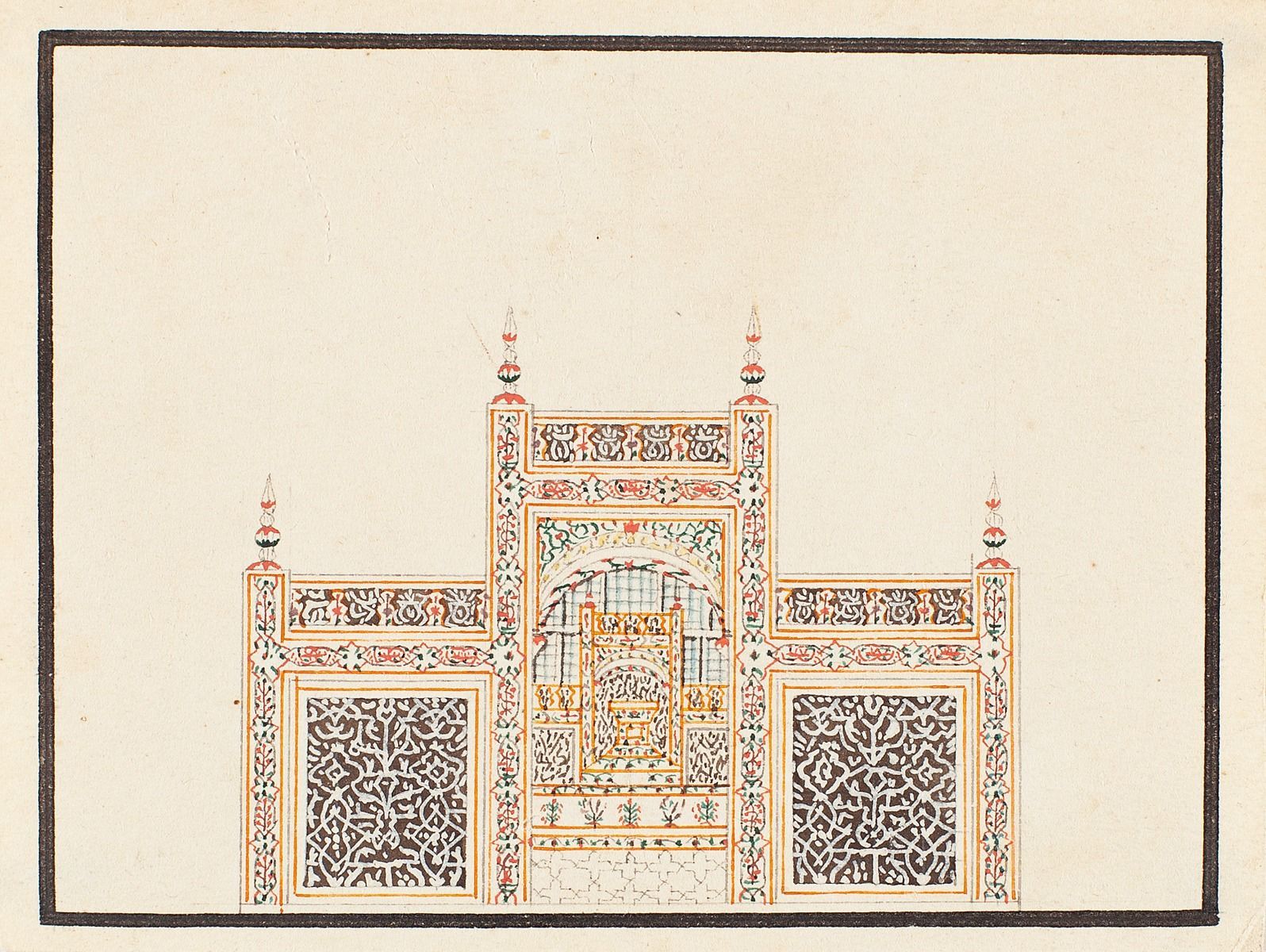

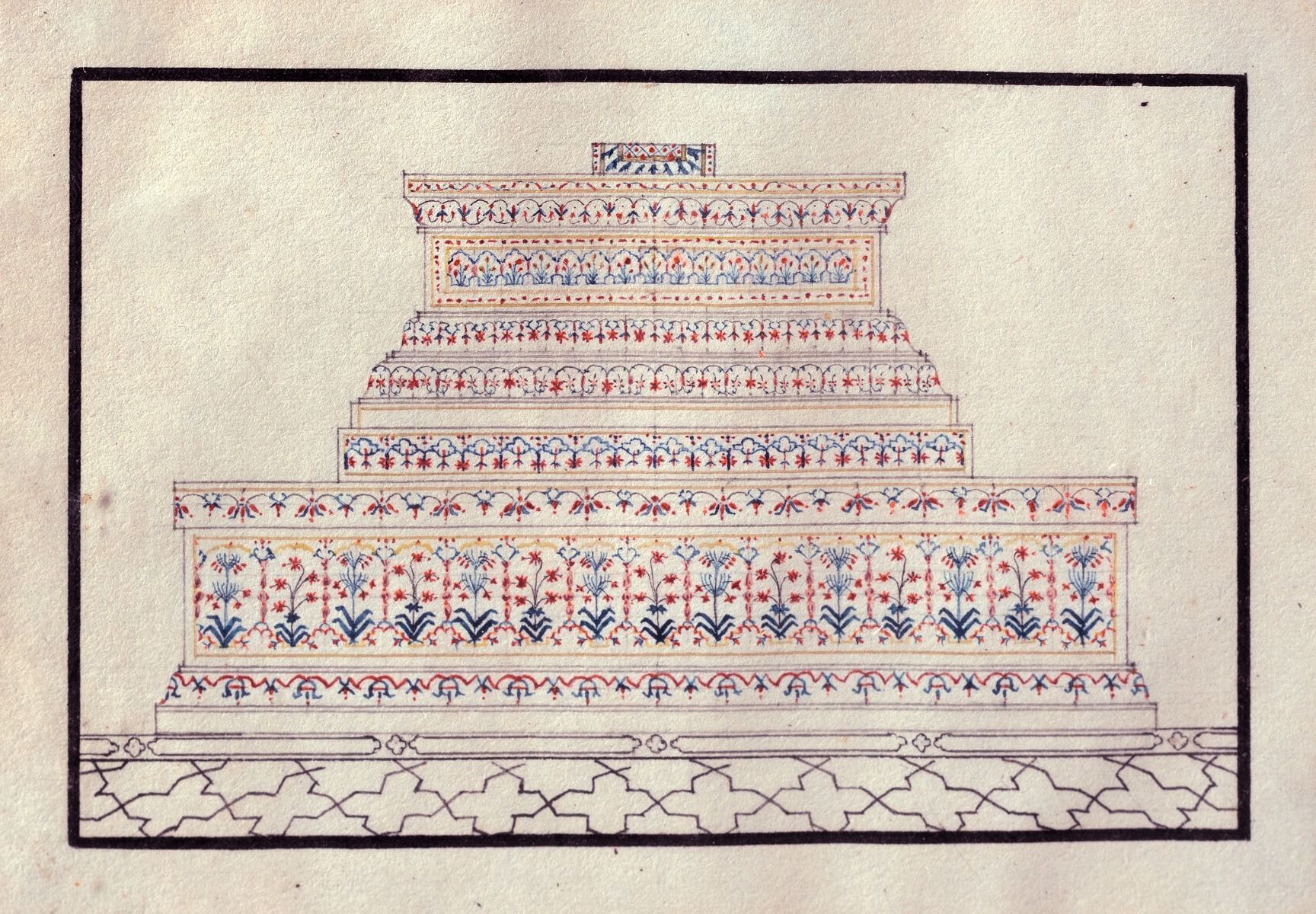

One of the sections includes paintings that focus on the intricate inlay work found on the interior screen and the tombs. You can easily spend an hour swooning over a single flower, stem or leaf or get enchanted by the beautiful calligraphic inscriptions from the Quran.

“The concept of the paradise is represented in Islamic art and architecture through calligraphy as well as geometric and arabesque patterns embodying peace, spirituality, and beauty beyond worldly perfections,” notes Safvi in the introductory essay in the catalogue.

One watercolour, possibly the smallest work in the entire exhibition (smaller than a postcard), meticulously records the floral and geometric patterns on the screen surrounding the cenotaphs of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal. The unnamed artist packs so much detail into such a tiny space that to appreciate it fully you have to take your nose right up to it and squint hard. A magnifying glass would have come in handy here.

Short of actually visiting the Taj, this might be the best way to go on a tour: in silence, peace, and in the company of supremely talented artists whose livelihood depended on close observation.

Through the exhibit, you also learn that the garden we see today is a modern interpretation. Nobody actually knows what the original looked like. The photographs here are from the late-19th century, when it had already changed in form, and they show a mini forest in place of the current manicured layout.

In fact, the way we see the Taj today is thanks to the English gardener AEP Griessen, who was responsible for restoring the gardens and vegetation and ensuring pleasant vistas. There are side-by-side layout plans from Griessen’s archive showing the garden from the late 1800s to early 1900s, and it’s fun to take a closer look and compare what all has changed.

The most touching work of the exhibition is a painting called The Emperor Shah Jahan Imprisoned at Agra by Hugo Vilfred Pedersen. It’s an imaginary scene from the emperor’s last days at Agra Fort, where he was imprisoned by his son Aurangzeb. The night scene shows a frail old man on his bed inside a dark room, lit by a single lamp, as he tries to get up to look—as if for one last time—into the far distance where the Taj shimmers like a mirage, bathed in blue moonlight.

As I left the gallery, I thought this is the way to see the Taj Mahal whenever I go back. With the deep longing and wistful eyes of Shah Jahan. Not through the clichéd images that fool you into thinking you’ve seen it all before.

The Mute Eloquence of the Taj Mahal is on view at DAG, Janpath, New Delhi, till December 6, from 11 am to 7 pm (Monday to Saturday)