Few nights after the year’s longest day, as London geared itself for the hottest (pun absolutely intended) party of the summer, one thing was amply clear. South Asian art is on a definitive, unmistakable ascent, and India is ready to claim its space in all its creative, cultural glory on the global stage. At least that is what we saw as the sun glazed over Dhaka-based architect Marina Tabassum’s pill-shaped 25th annual Serpentine Pavilion in Kensington Gardens, and the Serpentine Summer Party returned.

The Serpentine’s largest fundraiser is hosted by Michael R Bloomberg, chairman of the Serpentine’s Board of Trustees; Bettina Korek, Serpentine’s CEO; and Hans Ulrich Obrist, Serpentine artistic director; and co-hosted by actor, producer and humanitarian Cate Blanchett this year and is sold out.

South Asian art’s growing presence on the global cultural stage has been evident for a while, but what makes this edition truly special is that this year’s summer soirée at Serpentine does something quietly radical: it centres Indian art not as a theme but as a given.

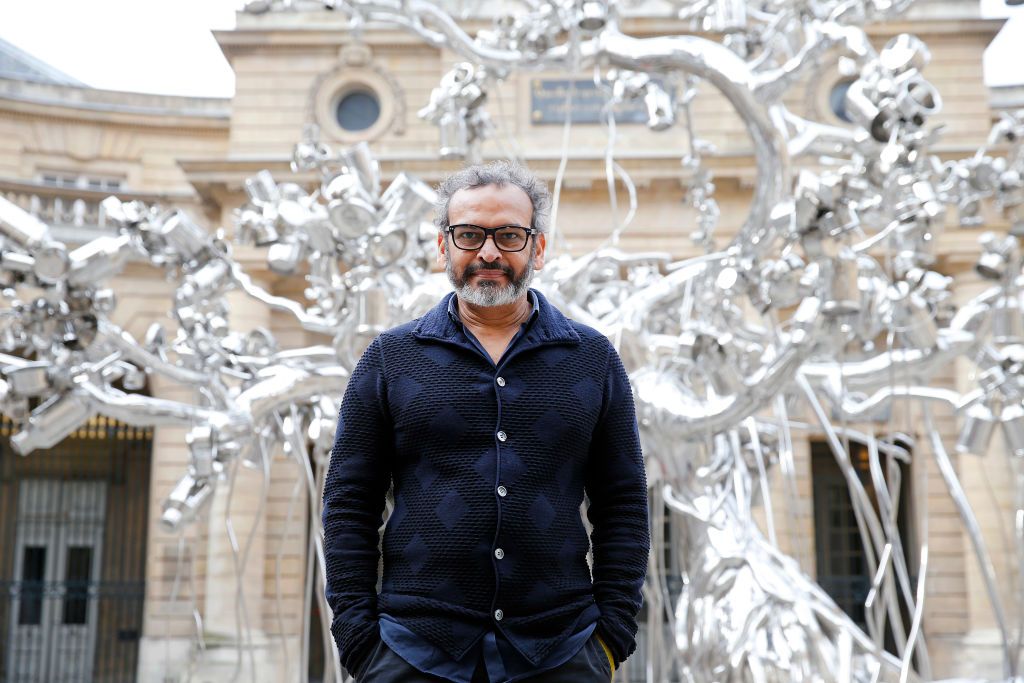

Even as artist Arpita Singh’s first institutional solo exhibit outside of India wraps at Serpentine North, at the heart of this year’s annual gala rests ‘A Place in the Sun’, a sculptural installation by Indian artist Subodh Gupta. This installation folds memory, movement, and material into something quietly monumental. Gupta’s work, which was unveiled today at the party, reimagines the archetypal Indian rickshaw conceived and constructed from domestic objects such as stainless-steel thalis, tiffin boxes, bicycles, and milk pails. It’s a sculpture rooted in familiarity, but it’s also dreamlike, drawing from a deep well of personal and collective memory. “The rickshaw in this work doesn’t aim to justify the struggle it represents,” Gupta tells The Nod over the phone, days before the unveiling. “It holds weight and dignity in its presence, evoking movement, endurance, and resilience. To me, it stands not only as a symbol of labour and journey but also of persistence in finding one’s place under the sun.”

Behind the rickshaw stands a vivid painting, ‘A Place in the Sun II’, which feels like an extension of the sculpture but also something entirely its own. Inspired by the hand-painted backdrops of traditional Indian photo studios, the image conjures the nostalgia of flights of Indian middle-class fantasies. There’s the thrill of a palm-fringed escape and the yearning for the coolness of a retreat in the hills that comes alive through the backdrop. “These images created imagined realities,” Gupta explains. “Small personal dreams captured in a photograph.” Together, the sculpture and backdrop form an emotional landscape that is as much about aspiration as it is about memory.

Gupta’s installation anchors a growing conversation around representation, materiality, and the invisible histories we carry with us. “I’ve been practising for over 30 years,” Gupta reflects. “The Serpentine is one of the most respected art institutions in the world, and to have my work shown there, even as part of a larger conversation, is something I’m very proud of.” One of the most striking features of Gupta’s work is the artist's ability to map the daily intimacy of Indian living onto universally resonant canvases of epic proportions.

To understand his work, one also has to understand where it comes from. Born in what he lovingly calls “the wonderland of Bihar”, Gupta’s largely self-trained path to art was anything but conventional. “When I was starting out, there wasn’t much access to formal art education or exposure to contemporary art,” he recalls. “There were no dedicated Art History professors around us to introduce us to artists or movements. We had to discover our own language.”

After moving to New Delhi, Gupta began his career with a small theatre group, painting posters before finding his way into art school. There he turned inward, by looking at the rituals of his past domestic life and the objects that surrounded him growing up. “From childhood, I was always drawn to the kitchen, its tools and smells. As an artist, those utensils, vessels, and domestic objects became not just materials but also carriers of meaning,” he explains. “That’s how the use of found objects, especially those related to cooking and home, became recurrent in my work. They are not just objects—they are also the universe to me.”

This deep, tactile intimacy with his materials is what gives Gupta’s work its resonance. As conversations flow past rotating canapes and glasses of champagne, Gupta’s rickshaw will continue standing still—anchored, contemplative, and demanding quiet reflection. And in doing so, it will remind us that the legacy of contemporary Indian art, beyond the confines of ancient stone sculptures and medieval miniatures, also perhaps rightfully deserves a place in the sun.

Subodh Gupta’s ‘A Place in the Sun’ is on display at the Serpentine Pavilion in Kensington Gardens, London