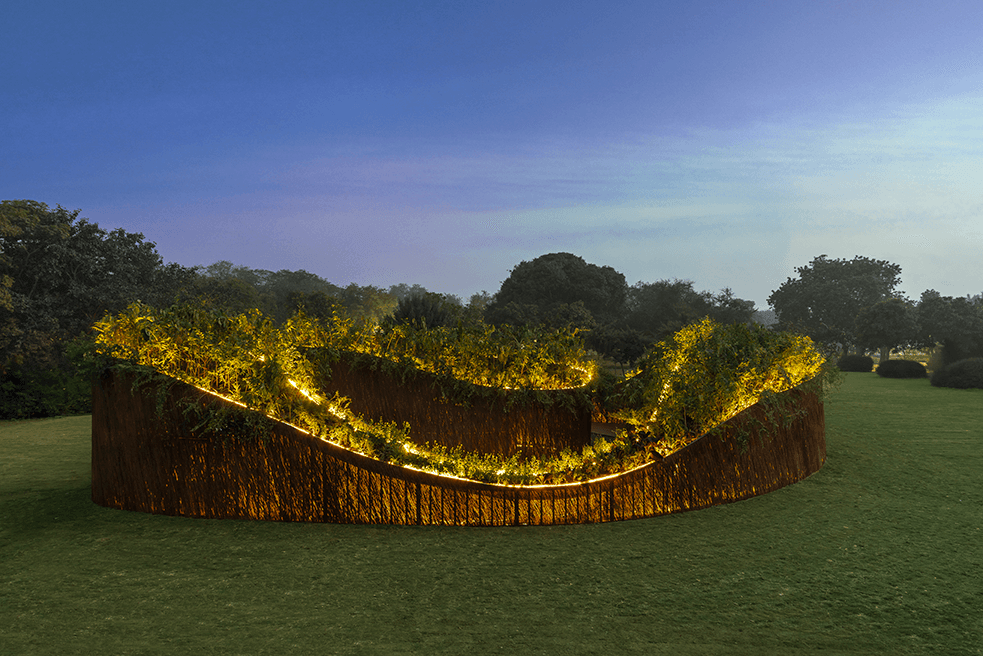

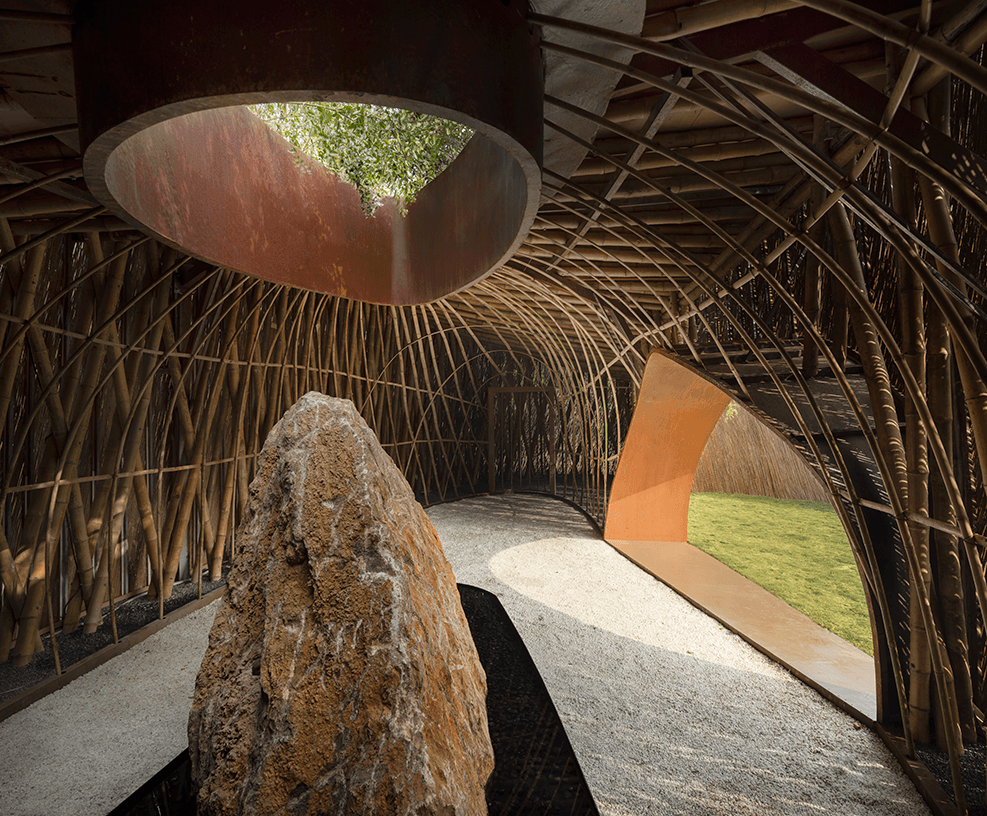

Sunder Nursery is where Delhi allows itself a little softness. You come here without a plan, without urgency, often without realising how long you have stayed. It is not wilderness, but it offers something close to permission. This month, nestled into this expanse of green, a spiral-shaped structure quietly takes shape. It is built from wood that does not belong here, planted with species that deeply do, and designed to be entered slowly. This is the Aranyani Pavilion, and it resists the city’s instinct to rush past meaning.

At its centre is Aranyani’s founder and creative director Tara Lal, 47, who splits her time between Delhi and Florence and has never really lived far from either design or nature. “We were always outdoors,” she says. “My father was very much an outdoors person, so holidays were in the mountains or by the sea. My mother had a garden and we were always surrounded by plants and trees. Knowing plants, knowing seasons, that was just normal.”

Growing up in Delhi in the ’80s, Lal spent most of her time outside, moving through gardens and open spaces without thinking of them as escapes or destinations. Nature, for her, was familiar rather than aspirational, something she absorbed early and instinctively. That familiarity is what later made its absence noticeable.

Design entered her life just as naturally. Lal grew up in a family where design was a way of seeing rather than a career choice. Good Earth, the design house founded by her mother Anita Lal, formed part of that environment, and she later went on to design for the brand herself after studying art history and architecture. Working within that world shaped her understanding of material, craft, and process, but by around 2010 something began to feel off. “I realised there was something more that I was seeking,” she says.

That realisation coincided with a growing discomfort with how life was beginning to feel increasingly screen-led. “I wanted to get away from screens as much as possible,” she says. “I wanted to start using my hands again.” So, she enrolled at Le Cordon Bleu in Paris, spending a year training in cuisine and pastry. The shift was not about changing direction so much as slowing things down. “Funnily enough, learning to work with my hands actually brought me back to working with nature,” she says.

That attentiveness soon moved out of the kitchen and into the field. Lal travelled to South Africa, where she became involved in conservation work. This was before conservation became an academic pursuit for her, and the work was physical, repetitive, and demanding. “A lot of the work that we did was like collecting data on things,” she says. “Things like rainwater levels and count of all the endangered species. We would have to keep track of birds and plants. The work was engrossing and tough, because every day you were out at 4 am and returned only in the evening. But it was some of the best times I’ve had.”

Formal training followed, including a Master’s degree in Conservation Science at Imperial College London, but the foundation was already laid. What interested Lal most was not conservation as control but conservation as relationship. “The people who really know about the land are the ones who live on it,” she says. “And yet so often conservation comes in telling them what they should be doing.”

She founded Aranyani in 2017 to create a different kind of space, one that brought together ecology, mythology, culture, and science. Lal speaks openly about how conservation has historically been shaped by colonial systems and a deeply masculine way of operating. “The masculine approach is to come in and say, let’s fix something by putting a fence around it,” she says. What she argues for instead is “to actually ask and listen to what people have to say” rather than separating them from the land they live on. “The feminine and masculine live among everybody,” she says. “I would like to encourage the feminine in everybody to come out.”