It’s a dark monsoon afternoon in Goa and in Kerala when Jeet Thayil and I meet over Zoom. It’s so dim on both sides that the air feels shared. His laptop is propped up on an anthology of Paul Bowles, and between us, through pixels and weather, the mood of The Elsewhereans, his dreamlike, borderless new documentary novel, lets itself in. “It is a kind of happiness to endure darkness in the afternoon with the expectation of rain,” he writes somewhere in the book. And we begin there, in that happiness.

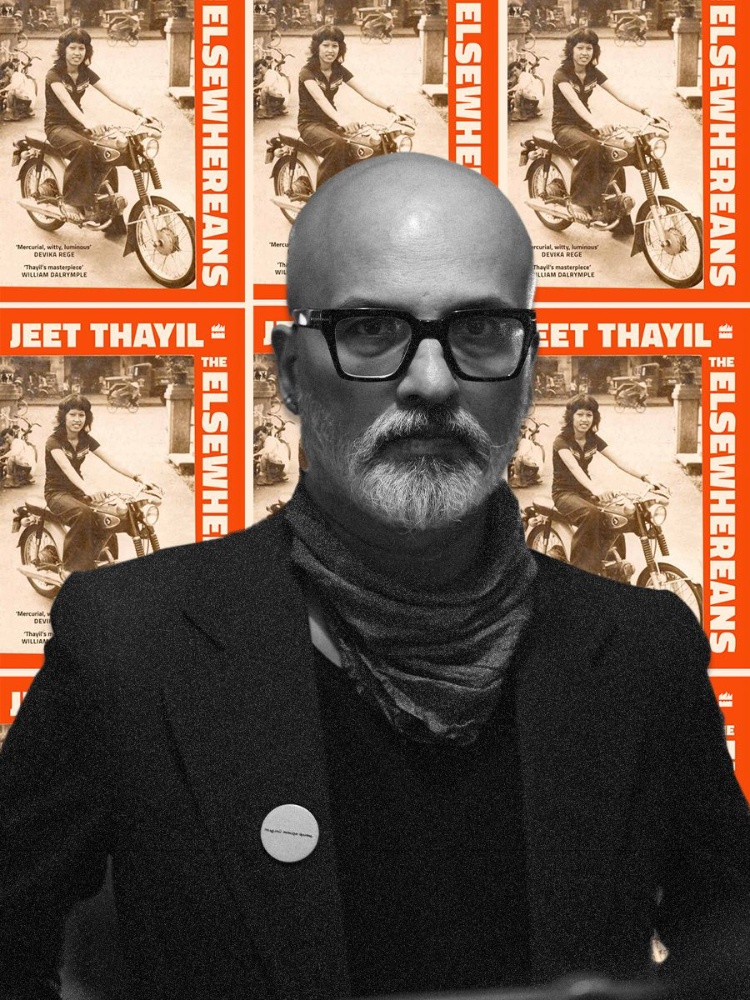

It’s been just two weeks since Thayil, a musician and author of the Booker-shortlisted Narcopolis, moved to Goa to escape familiar faces. He hasn’t nearly succeeded. “I wanted to not be at home,” he says. Home in this sentence translates to Bengaluru, a city where his parents resided, but in another might mean Mumbai, Kerala, Delhi, Hong Kong, New York, Paris—places he’s briefly called home. In each city, he has written himself in and out as poems, novels, songs. Narcopolis, These Errors Are Correct, Low, The Book of Chocolate Saints, all feature them. Themes of memory, faith, addiction, displacement, the dreamscape of grief run through them like a writer’s obsession. But his latest, The Elsewhereans, might be his most intimate and experimental yet—a novel built like a family photo album, flickering between memory and invention, documenting what can and cannot be remembered.

Even though it had all the makings of one, Thayil says he always knew The Elsewhereans wouldn’t be a memoir. “The great advantage of switching to fiction is that it allows you to dip into the minds of so many characters, which immediately opens the book up.” The novel follows Ammu and George, and the life they built, the homes they left behind, and the cities they salted into memory.

The book began, Thayil says, when he decided to become a son, leaving Delhi for Bengaluru when his mother fell ill. “I stayed and helped,” he says. “And I’m very, very glad I did.”

In the ease of doors left ajar in their Bengaluru home, it turned out that writing wasn’t such a lonely profession after all. “I would be working on something and wouldn’t be sure about a date or detail. I’d just walk across and ask.” His mother, then 90. His father, now 97. “They remembered everything. Names, dates, the order of things. They corrected me sometimes.” No phone calls, no waiting. Just the walk across the hall, a question asked and a memory handed back. He typed it on the spot before it slipped away again.

But writing about the living means asking them to live again. “I had to ask their permission,” he says. “Because they’re characters in this book, and they’re doing and saying things they never did in real life, as well as things they did. There would also be our extended family who might read it and mistake fiction for fact, but you can’t police a reader’s imagination, right?”