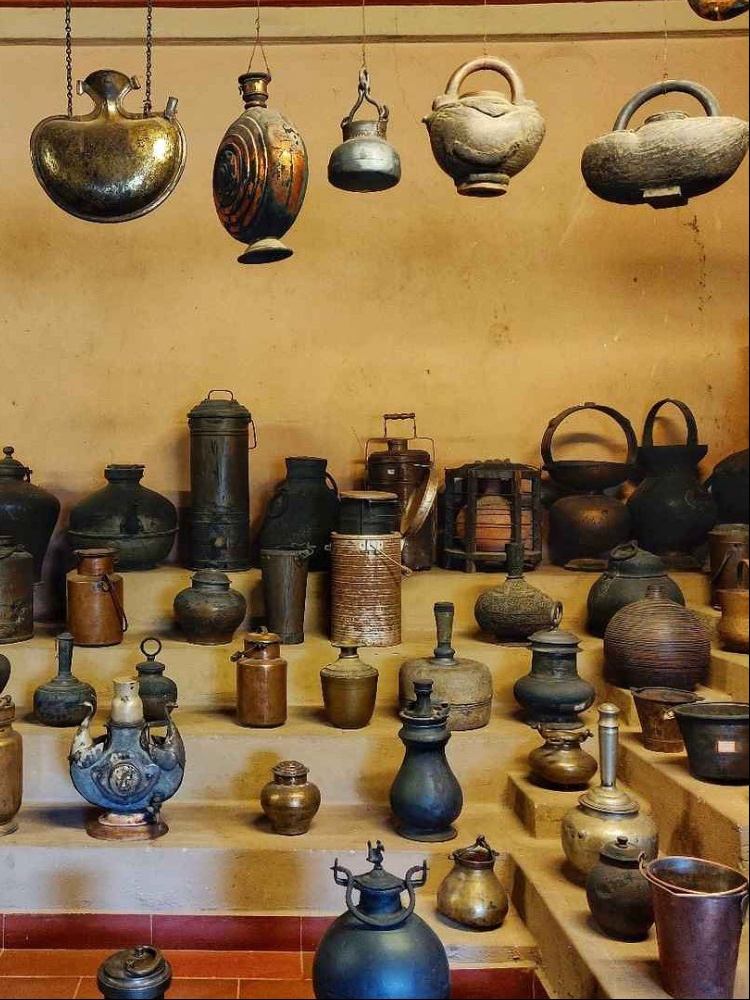

Decades before our kitchens started to look like ’grammable stations fit for Nara Smith, and our kitchenware started to mirror our obsession with millennial pink or whatever Pantone dictated, things were infinitely more interesting in that corner of the house. I’m at Ahmedabad’s Vechaar Museum, where over 4,000 utensils from India (the oldest dating back 1,000 years) on display confirm my hot take.

Within sight is a vessel used to churn buttermilk, jangly bells et al. There is also a metal rolling pin filled with pebbles, which today could moonlight as a percussion instrument for a world-music band. “Making mundane objects like these musical was done to reduce the boredom of household chores,” shares my local guide, Mukaram Sheikh.

Ahmedabad-based restaurateur Surendra C Patel is a collector and also the founder, curator, architect and designer of this unique utensils museum. “Back in 1978, I was looking for antique vessels for my restaurant, Vishalla. I travelled to nearby villages and discovered that people were melting down vintage vessels, not realising they were antiques or the value of their designs. I remember buying a bag of lotas at ₹30 per kilo with the idea of preserving and using them. That was the start of this project,” recalls Patel.

Vechaar, which stands for Vishalla Environment Centre for Heritage of Art, Architecture and Research, was set up as a museum of kitchenware in 1981—37 years before celebrity chef Vikas Khanna launched The Museum of Culinary Arts at Manipal’s School of Culinary Arts. Unlike the mammoth museum in Manipal, this one started out as one man’s passion project. Tucked away inside Vishalla Restaurant, a Gujarati thali space in Vansa, Vechaar Museum may be smaller, but it holds everything from gargantuan storage jars that could fit a family of four to one-of-a-kind samovars from Uzbekistan.