Here’s what conventional wisdom tells us: longer waits frustrate customers, damage loyalty, and hurt sales. Yet recent consumer psychology research reveals something far more counterintuitive. Studies from Georgetown University’s McDonough School of Business found that customers who waited longer actually purchased more. Diners wanted longer meals after waiting for tables, shoppers bought more items after queuing at sales. The mechanism is simple: when waits are prolonged, customers interpret this as social proof that the product is worth having, valued by others, desirable enough to justify the investment of time.

Research also shows that while resource scarcity can narrow options, product scarcity tends to increase perceived value and shift consumers’ willingness to delay gratification. The wait itself becomes part of the experience, part of what makes the final purchase mean something. Time becomes a filter, separating genuine want from algorithmic impulse.

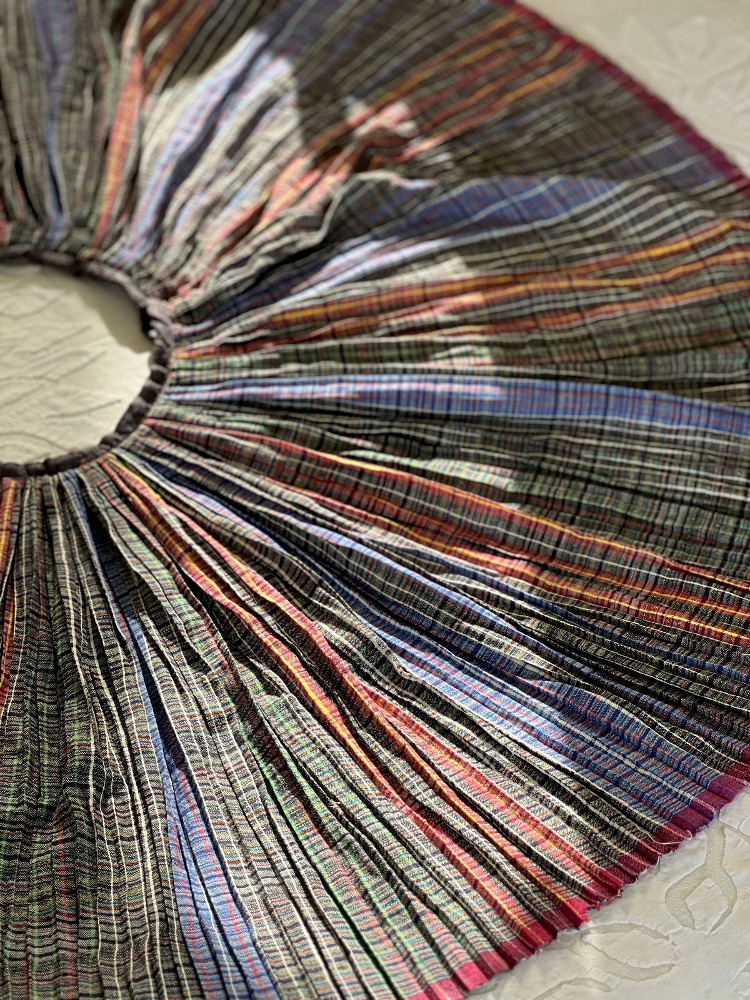

These are learnings that the fashion industry is leaning on too as a growing number of young designers opt out of ready-to-wear entirely. No stock. No racks. No frantic end-of-season sales. What’s on offer instead is made-to-order clothing: customised, slow, and deliberately unhurried. The question is no longer who will wait, but why waiting suddenly feels like the point.

Waiting, but make it intentional

At brands like Re-Ceremonial, founded by Ateev Anand, waiting feels entirely appropriate. Focused on ceremonial and occasion wear, the label operates on the understanding that meaningful clothing doesn’t need to be rushed. These garments are destined for weddings, milestones, rites. Moments that come with their own built-in anticipation.

“The only space where we could really expect the consumer to have patience and give us the time needed to create a truly ethical, consciously made product was in the made-to-order ceremonial segment,” Anand explains. “Within that, people already had the mindset to let us explore the techniques that need not just resources but also time.”

The process unfolds across three crucial stages: design, development, and execution. The timelines for each vary wildly. Some clients spend six to eight months just in design conversations because the emotional stakes are that high. Others move quickly through design but invest heavily in execution.

What makes this work is that clients don’t see time as a concession to slow production. They see it as their own investment: a way of being present in what they wear. “The patience that it demands from them is part of the investment, not just the monetary investment,” Anand notes. “It’s not just lead time we’re offering. It’s the amount of time they need to be involved so that a whole facet of them comes through.”

Many become patrons precisely because of this evolving relationship. Re-Ceremonial doesn’t just design one outfit for one event; they build wardrobes around key pieces, returning to develop new looks that build on what already exists. This transforms the transaction into a conversation.