In the early 1980s, in Thatcher’s Britain, a little-known British-Indian band called Pinky Ann Rihal was busy inventing a brand-new sound—Hindi new wave. Their debut album—1986’s Tere Liye—was a compelling, free-wheeling amalgamation of woozy synths, prog-rock guitar riffs, syncopated drum patterns and charmingly amateurish Hindi vocals. Funky, tense, and quirky in equal measure, the music on Tere Liye still feels vital and subversive today.

This was pre-internet and pre-Spotify, when Indian audiophiles would rely on their families abroad to bring back some music. But Tere Liye didn’t achieve that cult status. In fact, the album sank without a trace, and the Mumbai-based label that put it out failed to do any marketing around it, even incorrectly labelling it as “Hindi disco”. A customs issue held up the shipment of records at Heathrow, and South Asian record stores in Southall refused to stock the few copies that made it through. The biggest problem was that, in the pre-streaming, pre-globalisation era, their music fell into a cultural no-man’s land—too brown for the West, too Western for South Asia.

“It’s a pattern we see over and over again, where a South Asian act would come up with a cool new sound, record an album, but then get zero support from the industry,” says Raghav Mani, co-founder of Los Angeles-based label Naya Beat Records, which reissued Tere Liye in 2022. “Western labels would say, this stuff is too South Asian for us. An Indian label might grudgingly put it out but do nothing with it. And then these amazing records got lost in a storage unit or were just thrown away.”

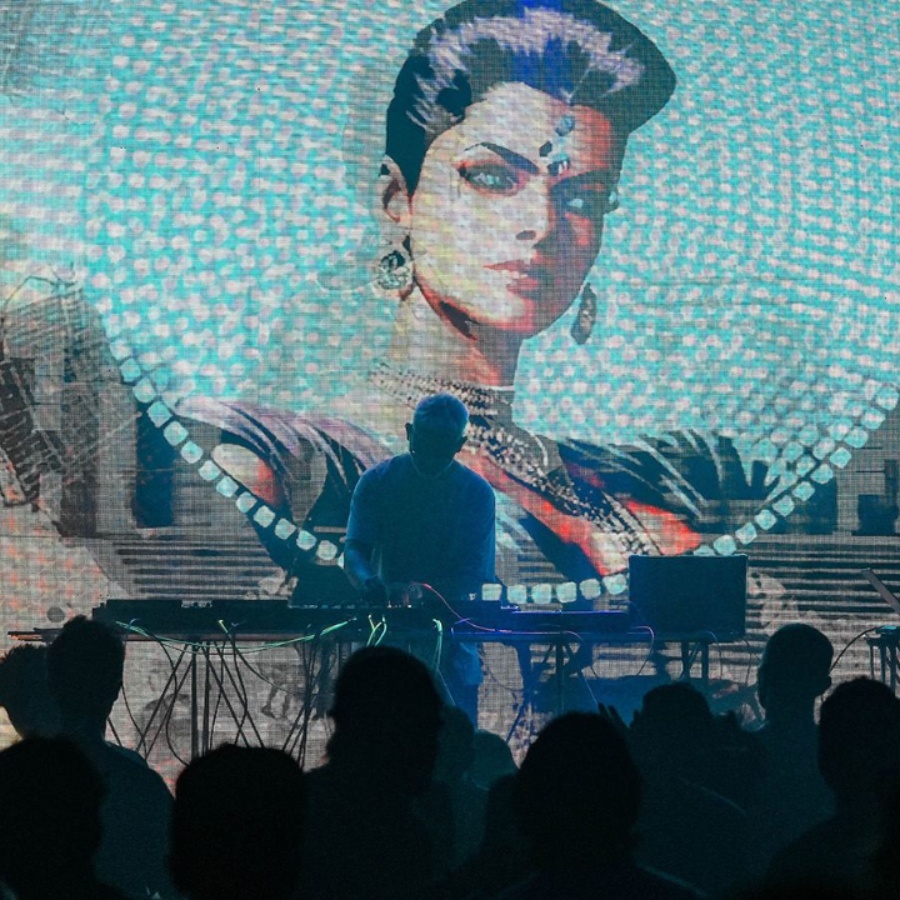

With Naya Beat, Mani (aka DJ Ragz) and co-founder Filip Nikolic (aka Turbotito) aim to give forgotten gems like Tere Liye—and the people who made them—a much-deserved moment in the spotlight. Like crate-digging archaeologists, they’re unearthing forgotten chapters of our musical past, rewriting history to highlight the unsung heroes of late-20th-century South Asian music from India and the Indian diaspora.

“It’s not about unearthing dusty, mothballed music just because it’s old and obscure,” says Mani of the label’s curatorial focus, which has so far included Balearic pop from Mumbai, bhangra-house from the UK, and soca-infused chutney music from Trinidad and Tobago. “We want to find and put out South Asian music from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s that was cutting-edge and timeless—stuff that’s just as relevant today as it was when it first came out.”

Like many of music’s best origin stories, this one too begins in a bar. Specifically, Gold Diggers, a dimly lit former strip club in LA’s East Hollywood, home to a popular party called Heatwave, where resident DJs Daniel T and Wyatt Potts would spin funk, disco, and house records from all over the world. That’s where Mani and Nikolic first met.

We want to find and put out South Asian music from the ’70s, ’80s, and ’90s that was cutting-edge and timeless—stuff that’s just as relevant today as it was when it first came out.”

It quickly turned out that the two had a lot in common, beyond a shared affinity for cross-cultural sounds. They were both quintessential third-culture kids. Mani was born to Indian parents in the Philippines and grew up in Geneva. Nikolic is from Denmark and spent time living in Yugoslavia as a kid before making his way to Los Angeles. Both also had fathers with deep, eclectic record collections and a love for audio gear—passions that they would soon inherit.

Sometime in 2019, Mani began working on a mixtape culled from obscure South Asian dance and electronic records from the 1980s that he had picked up over a lifetime of crate-digging. But no matter what he tried, the mixtape just didn’t sound right. His friend and DJ Daniel T pointed him to Nikolic, who had already gained a reputation for his unique approach to mixtapes.

“When I was with [American chillwave band] Poolside, I made a couple of mixtapes where I would pretty much edit all the music, do additional production, and remaster the tracks, all to make it even more seamless,” says Nikolic. “And that was the perfect approach for the music that Ragz had, because the audio quality was so rough that it would hurt you to listen to it at a club.”