‘Giving people stories is not a luxury. It’s actually one of the things that you live and die for.’

I can’t tell you what I ate yesterday, but I can describe the exact moment, 10 years ago, when I read the Neil Gaiman anecdote that ended with this line in microscopic detail. Because it made something inside me split open and spill out in a way that’s only possible when you’re young and naive and hopeful about the world and your place in it. This line is my Roman Empire.

For years now, I’ve held on to every word Gaiman has written—books, ramblings on his online journal, pithy pronouncements on Twitter, Tumblr, and Bluesky. I cheered his stealth book signings, fangirled over his book covers, and took pride in his outspoken, erudite allyship with the LGBTQ+ community. A running joke between close friends was: “What do you want to be when you grow up? Neil Gaiman.”

Separately but simultaneously, I’ve also endlessly debated the morality of consuming tainted art. Can we separate great, life-changing art from artists who have since revealed monstrous cores so we may consume said art without also being consumed by the guilt that comes with wilfully turning the other way? Can an artist exist as both—a generational talent and a violent sexual predator—in our heads and hearts?

Can we separate great, life-changing art from artists who have since revealed monstrous cores so we may consume said art without also being consumed by the guilt that comes with wilfully turning the other way? Can an artist exist as both—a generational talent and a violent sexual predator?

Both these preoccupations came crashing together for me in January 2025, when New York Magazine’s exposé of much-celebrated author Neil Gaiman’s pattern of sexual abuse came out. Eight women with eerily similar accounts came forward with their stories of exploitation, abuse, and assault. NDAs were signed and broken. Gaiman, of course, issued a non-apology—it didn’t happen; okay, some of it happened but it’s not what it sounds like; I’m reflecting and working on myself. I’m sorry, but no, I won’t apologise.

For me, it was acute bewilderment.

Even if you didn’t care for his writing, it was hard not to like someone who seemed so genuinely nice. Sensitive, open, honest. Sometimes cringey, but only because of his eagerness to overshare his sex life. In many ways, he was the perfect salve to the deep wounds left behind by JK Rowling’s escalating TERFiness. Which is why his betrayal felt twofold—I had invested in him as a prodigious artist but also a person. Gaiman was supposed to be safe. We had years of social media dedicated to fostering that image as proof. He had led me to believe so—that I knew him. Naturally, I wasn’t just affronted; I was also hurt.

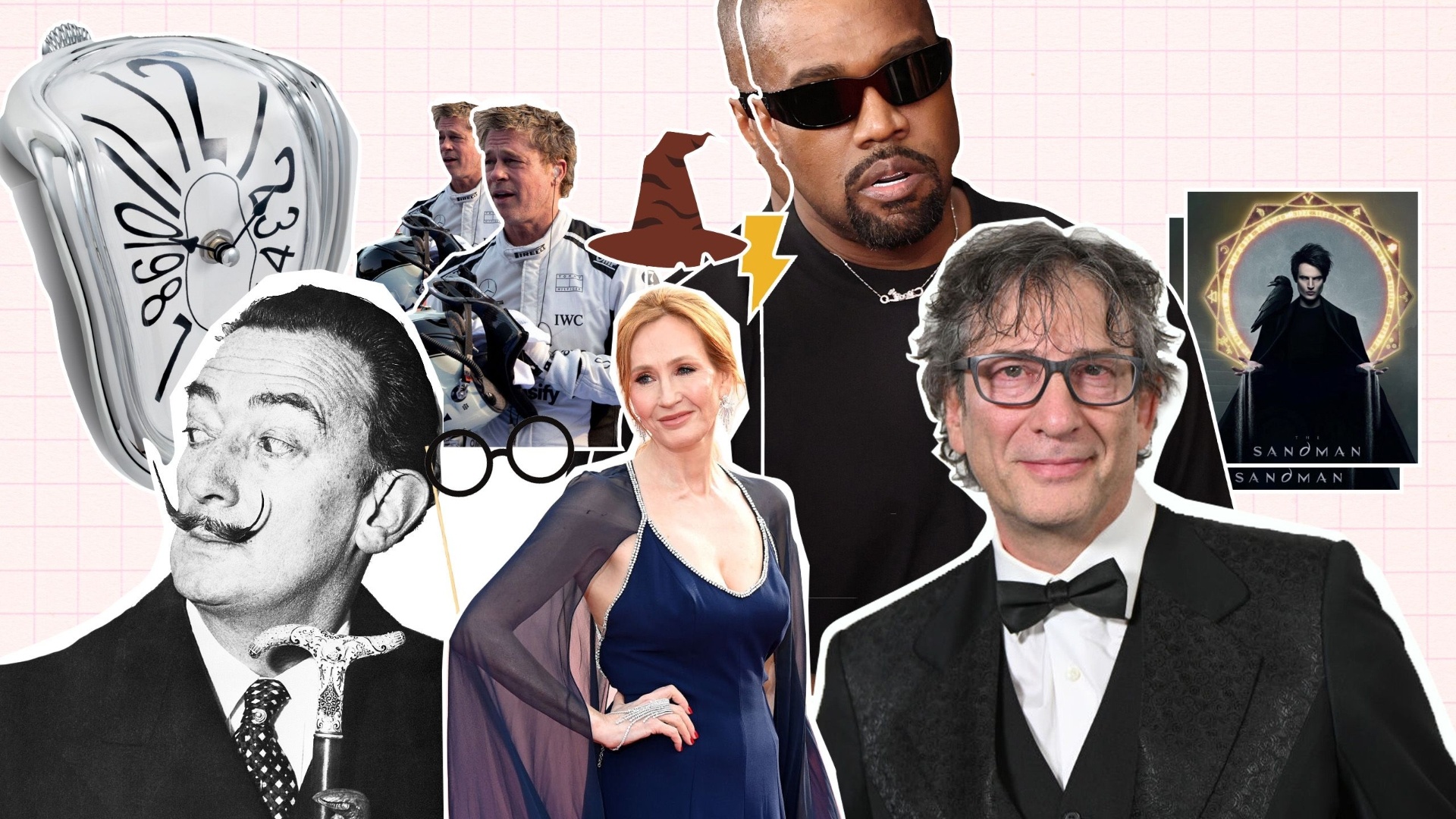

Gaiman and Rowling are but two within an ever-growing pantheon. The list includes Alice Munro (supported the husband convicted of abusing her pre-teen daughter), Picasso (abuse of minor “muses”), Paul Gaugin (polygamy, and sexual abuse of minors), Eric Gill (sexual abuse of teen daughters), Michael Jackson (child molestation), Johnny Depp (domestic and sexual abuse), Brad Pitt (physical abuse of wife and children), Louis CK (sexual misconduct), Chris Brown (physical abuse), P Diddy (rape, abuse, sex racketeering)…

It’s evident that the pantheon always existed; it’s just a lot harder to pass off ghastliness as a tormented artist’s eccentric mind, or, worse, process in the age of social media, screenshots, and cameras always on the ready. Could Salvador Dali have survived the scrutiny if his extreme racism, fascism, and necrophiliac impulses had been immortalised on Instagram? Who knows.

“There are no more gods,” says my friend Aditi Mittal, a standup comic from Mumbai. “And that’s perfectly okay. I don’t want to judge my favourite artist just for their art. I want to know if he’s a wife-beater. It tells me that my adulation was not treated sacredly by him. That he used the power it gave him to do unspeakable things. I want to take that power back by cutting him out of my life completely.”

My brain knows this. It knows what is right, what I must do, and it makes me do it even though it also knows that barring a handful of the vilest offenders, there will be first soft and then full-fledged comebacks. Powerful people, especially men, in the arts have their redemption arcs practically written into their unmasking stories.

Just look around: Dave Chappelle is back at telling jokes, Kanye West is still releasing albums, and Johnny Depp, well, looks like he never went away. And Woody Allen, after publishing a memoir among all the furore, is back with a new novel. And for all of JK Rowling’s very public diatribes, she’s added about $80 million annually to her existing billion-dollar empire after she went public with her gender fundamentalist views and is slated to earn another $20 million a year from the WIP Harry Potter reboot. She continues to maintain profit participation, executive producer credit, and substantial creative control. Where’s the reckoning, really?

I didn’t watch F1: The Movie among all the fanfare surrounding it. Until last year, I was giddily waiting for The Sandman season two, but now that it’s out I can’t bring myself to look at my mopey hero without thinking of Gaiman’s victims. My decision is final, even for the Harry Potter TV series that recently announced its cast.

Younger me was not so resolute. I’d convince myself that as long as I was watching pirated versions of Woody Allen’s movies, I was fine. I was sticking it to him without having to feel bereft. But somehow, it felt dirty. Like I was a gender traitor who was now complicit in his crime. And, secretly, hatefully, I still found his movies moving. Where does my personal responsibility lie?

There’s no single straightforward answer. For London-based tech consultant Vishala Reddy, it’s all very cut and dry: “It’s always the idolised artists that end up using their power to exploit women. That power comes from us. I absolutely do not want to be someone who enables a problematic artist’s work, lifestyle, power and privilege, even if they’ve managed to get a pass from the rest of the world.”

In sharp contrast is Vinay Santhosh, a chef from Bengaluru, who talks about how a work of art is rarely one’s own. “Most art is a collective effort. So many lives are attached to it. Are we saying that all of them deserve to have their work cancelled for sins they had no knowledge of or control over?” he argues.

Most art is a collective effort. So many lives are attached to it. Are we saying that all of them deserve to have their work cancelled for sins they had no knowledge of or control over?”

And somewhere in between is Delhi-based development sector professional Sheena Chandel. “There are times when I have, despite my best intentions, allowed myself a cheat concert or a cheat movie if I feel like I’ve boycotted enough,” she admits. “But the one thing I’ll always do, even while I’m consuming the work of disgraced artists, is talk about what they did. So, in that way there is no separating the art from the artist.”

I’ve come to realise then that personal responsibility is a shape-shifting concept. Even if I’m choosing to end my relationship with all four, I’ll always be madder at Gaiman for deliberately misleading me for years than JKR for not revealing her true self before. Picasso does not get a free pass because he’s dead, but it certainly helps that he is. And maybe I’ll be less mad at Michael Jackson once he’s been dead for as long as Picasso.

Personal responsibility is also undeniably painful. How many books, movies, and songs do I delete from my life’s archives, even if such a thing were truly possible? How many museums and exhibitions do I refuse to enter? How many times can I bite my tongue to curb the instinct to mouth a particularly moving line, lyric, or dialogue? And, most fearfully, who am I, stripped of all my most powerful cultural anchors?

That’s the thing about art that brands you—good art stirs who you are in the now, great art reunites you with all the versions of you that you leave behind.

I wish someone smarter than me would come up with an objective formula to give me a culpability score. One that weighs the cultural importance of the art against the severity of the crime, the level of the artist’s duplicity, and the social and financial capital they stand to gain with each individual endorsement. A sliding scale of yellow, amber, and red alerts for influential yet crappy artists.

But in the absence of such tidy solutions, the question that keeps bouncing around is: What do we do now? Where do we go from here?

“We stop bitching and start trying [to find other artists],” offers Mittal. “It’s work and it’s not glamorous, but then that’s what personal accountability looks like. Everything else is noisy virtue-signalling, no?”

Fair enough. And I did.

I recently discovered Jenna Jensen and her Dante’s Equation. It excited me in a way I haven’t been excited by a new book in years. It combines the ideas of good and evil with theoretical physics. There’s a fifth dimension and also a Holocaust concentration camp. And, of course, unrequited love. It’s been around for 22 years as a not-unknown-but-not-successful genius book that not enough people know about.

And maybe that’s the only thing we can do if the doing is actually as important as the raucous raging for public consumption. Quietly, bit by bit, start pouring our love into other vessels. One book, movie, canvas, or song at a time. There may be no more gods, but there can be new good omens.