There’s something deeply enigmatic about the anonymous artist. From George Eliot to Elena Ferrante in literature, the Gorillaz (initially) to Glass Beams and Talwiinder in music, and Banksy to the Guerrilla Girls in art—every era and universe has its share of creators who’ve let their pencils, brushes, and instruments do the talking. To court fame without wanting to be famous: it’s a curious paradox and, in our follower-obsessed, post-digital world, a deft sleight of hand.

“Being anonymous is like seeing the world through a viewfinder—focused, intentional, and quietly distant,” says the artist Natasha Preenja. Sitting in the conference room at Tarq Gallery in Fort, Mumbai, on the opening night of her new exhibition, the Gurgaon-based artist is trying to patiently answer the one question she’s presumably already tired of hearing. She is, of course, Princess Pea, the multifaceted and thus far anonymous artist best identified by her green bobblehead-like headgear, who has, through two decades of prolific work, interrogated femininity, invisibility, and the crushing expectations placed on women in patriarchal India.

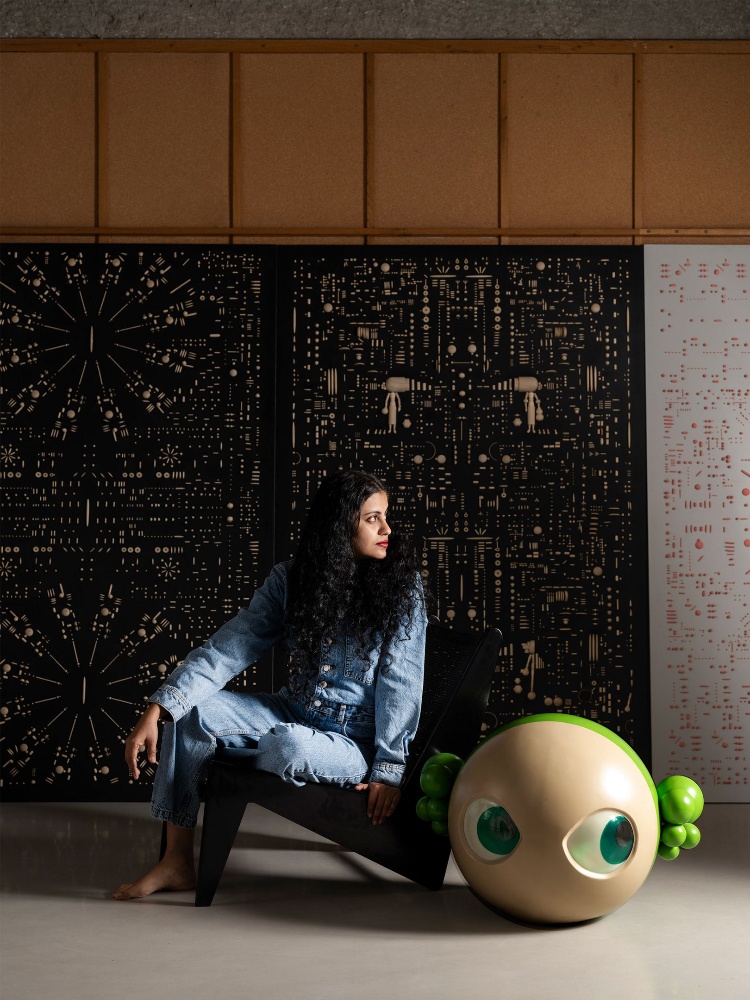

This is probably the first time in 16 years that Princess Pea has appeared in public without that iconic oversized headpiece—the “living toy” that defined her alter ego who could not speak, smell or hear, existing somewhere between fairy tale and harsh reality. Turns out, under that headgear lies a mop of curls, a ready smile, and those liquid anime eyes that, in her youth, evoked consternation and comments about “staring”.

“It wasn’t like a scheme, or a plan, or a career move,” she laughs. In fact, back then, she invented that headgear to protect herself and her sister from criticism for their appearances as they began to venture beyond the safe environment of the army cantonment in which they grew up. Later, it became methodology: a way to understand herself while creating space that belonged only to her.

Over time, the mask travelled from body to body, and that intimate space has expanded to include hundreds of women—artisans, housewives, survivors of abuse, those wrestling with mental health and body image—as they went about their lives, “a silent choreography of pleasing and proving”. The decision to reveal herself now, Preenja suggests, reflects how she and her practice has evolved: “From a girl to a woman, and now a mother. We play roles, we change, we age, and we expand our own selves into more: more care, more resilience, more ways of being. With my growing inclination toward community practice, I feel that Princess Pea has also expanded, no longer a single self but infinite women.”

The exhibition, वज़न, itself marks a material departure for Preenja. Where her earlier work centred on performance and digital manipulation (the satirical Vague series featuring doctored magazine covers) and small turned-wood toy sculptures made in collaboration with artisans from Etikoppaka village in coastal Andhra Pradesh, वज़न introduces marble and hand wooden block printing.

The new marble sculptures, titled ‘Mothers, Bodies of Stone’, depict women bearing invisible weight—the accumulated burden of expectations, domestic labour, and silenced pain—carved in a material historically associated with masculinity. “Over the years, I have made thousands of drawings, many of which were later chiselled in tree bark. I wanted to expand their scale and explore another material language,” Preenja says.