Several works in Gul take the shape of a charbagh, but none with conventional materials. ‘Tear Fed’ turns a moth-eaten Kashmiri shawl into a map of paradise, stitched with scrap brass jewellery, mirrors, and beads. ‘The Eternal Garden’ follows the same layout, only this time with vintage ledger paper, shaving blades and flowers that refuse to wilt. And in ‘Can I Call You Rose’, the garden returns once again, except the centre is left empty, a void to mark everything history took and never gave back.

At Wolf Jaipur, sustainability is not a keyword. It is simply how things are done. They build from what already exists. “We had so many old things lying and there was the idea of why we should get new. Let us use what we have and think of new ways of putting it out,” Ritu says. This way of thinking began at The Farm, their home and studio just outside Jaipur, long before the word ‘upcycling’ became an Instagram hashtag.

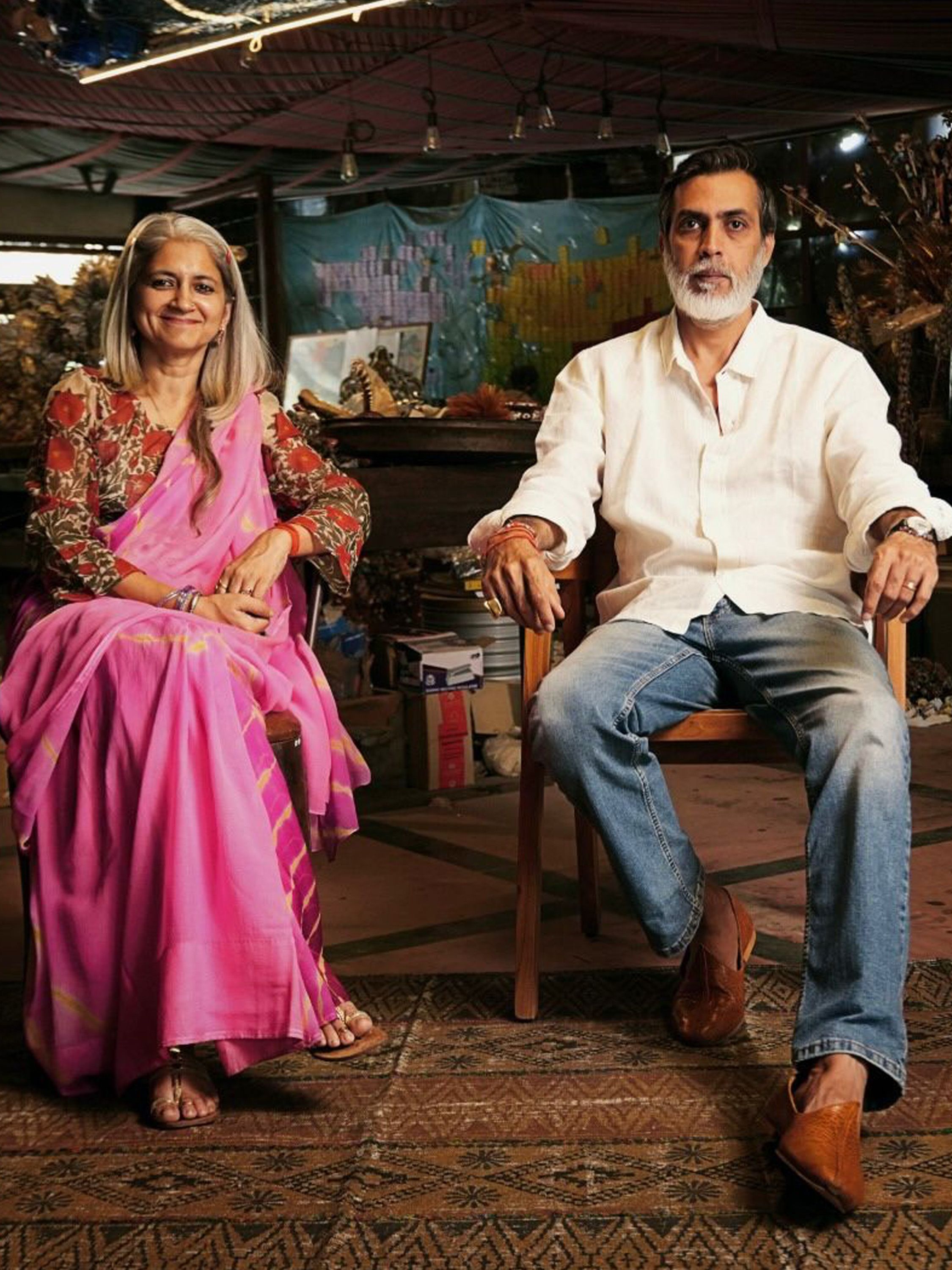

The Farm, which started as a blueprint for a concept hotel, itself grew from loss and memory. Surya’s ancestral house near Udaipur was submerged during the Mahi Dam project, and his father salvaged what he could—doors, beams, windows—some over 200 years old. Those pieces now hold up The Farm. Neither Ritu nor Surya studied art. They learned by bending metal, breaking it, and trying again. Wolf was born here in 2013, not as a company but because they could not stop making things.

Nothing at The Farm is symmetrical. A bar turned into a kitchen. Guest rooms became family rooms. Iron sheep and poppies stand around like permanent residents. Materials arrive from flea markets, junkyards, roadside scrap, forests, forgotten cupboards, and whatever crosses their path. “Bits of everything,” they say. Sometimes an artwork begins with an idea. Other times, with a chance discovery. “There is a whole piece ready and one part missing, and suddenly it is sitting at a roadside stall under a chadar,” Ritu says, laughing.

The duo often found inspiration in Mughal miniature paintings, but their scale is anything but miniature. Works like ‘Tear Fed’ span almost 6 x 6.6 feet and ‘Can I Call You Rose’, over eight feet long, is taller than most door frames. Their earlier installations were even more ambitious. In their early years, Wolf created metal poppies towering over people, forests made from discarded paper, rooms turned into living installations. Their work has appeared across the country, from O Pedro in Mumbai to Pepper House in Kochi, in schools, hotels, and even street corners.

In 2024, they created ‘Bombay Rising’ for Art Mumbai, where 1,100 metal poppies bloomed at the racecourse. At the 2023 Kochi-Muziris Biennale, their installation ‘Eye Spy’ used palm leaves, Theyyam scraps, film negatives, and fishing buoys to ask viewers to unlearn and look again. These were works you could walk through but never take home. It was only after working with Srila Chatterjee of Baro Art that they realised people wanted to take a piece of their world home. The 17 pieces that make up Gul do not rush to heal or conclude. They linger. They let the silence sit. And they remind us that gardens were once places of shade, poetry and public life, and somewhere along the way we traded them for fences, lawns and ticketed entry.

And that’s where Wolf stands, not in mourning but in rebuilding. They do not write manifestos or wait for perfect conditions. They gather what the world discards and begin again. No formal training. No blueprint. Only persistence, rust, and a poet from the 18th century whispering in their ear.