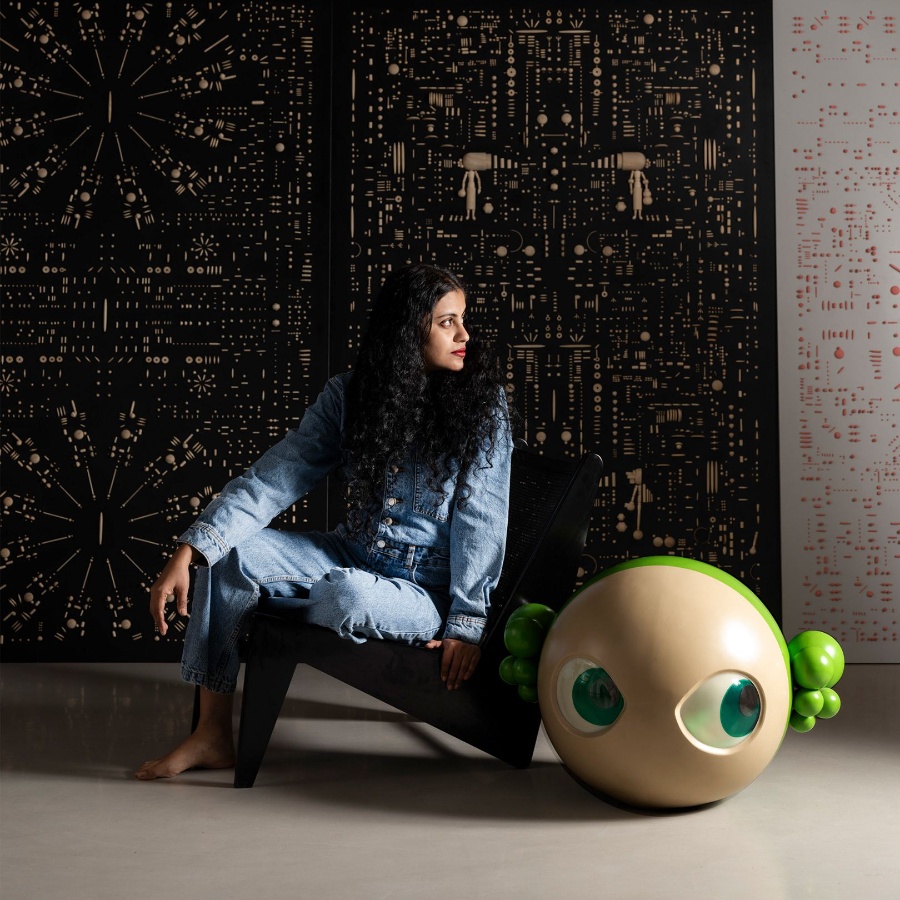

Goa-based multidisciplinary artist Rhea Gupte’s most extensive and introspective body of work began not in a flashy studio but within the quiet confines of her kitchen. In the Covid-19 pandemic, while the rest of the world coped by baking banana bread and whipping Dalgona coffee, Gupte found herself drawn to discarded food scraps that accumulated after a day of cooking—eggshells, orange peel, onion skin, and wilted greens.

“My partner and I began freezing our wet waste to be thrown into a compost pit, and the resulting medley of colours, textures, and patterns sparked my curiosity and imagination. I wondered what these would look like as still-life portraits,” she says, recalling the moment that led her to create 89 frozen installations that would eventually be known as the Compost series, currently on display at Bleur gallery in London.

It was especially timely, considering the mass food shortages and empty supermarket shelves witnessed in the wake of the lockdown that exposed the fragile distribution system of a basic necessity. “The transient nature of the frozen installations brought to mind the impermanence of our natural resources and the things we take for granted. Food is always political: the way it’s grown and who grows it, how it reaches us, who gets access to it, and who disposes it. The reality remains that a majority of the population on this planet starves every day,” Gupte explains.

By reimagining everyday kitchen waste as evocative portraits, Gupte not only forces us to confront our own wasteful patterns of consumption and food privilege but also challenges conventional notions of what can be considered art. Potato peel, leek stubs, capsicum seeds, and other scraps that are discarded into our dustbins without as much as a second glance are now protagonists that sit in visual harmony and invite viewers to ponder on cycles of growth, decay, and renewal.