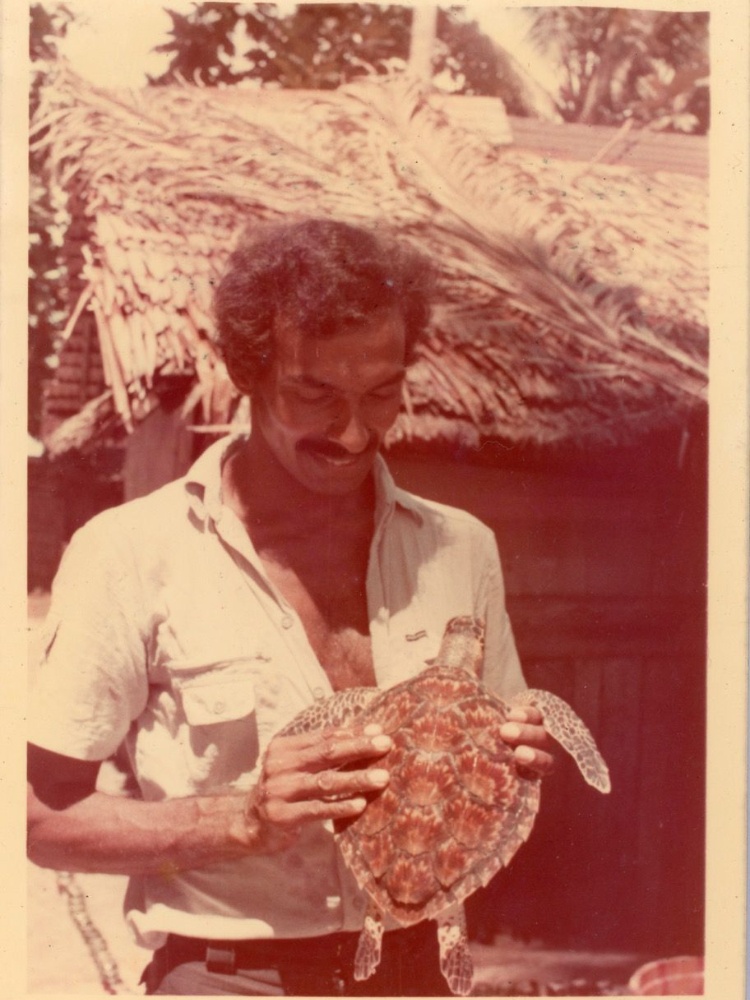

In 1982, a small-framed, lean man named Satish Bhaskar arrived on an uninhabited island in Lakshadweep. There were no maps, no cell phones, no human habitation—just an uninterrupted view of the cerulean, froth-lipped Arabian sea. His backpack carried a notebook, transistor, camera, snorkelling gear, basic medicines and food. For the next five months, Bhaskar would make Suheli Par—a lush green, oval coral atoll in the middle of nowhere—his home.

The modern-day Crusoe was on a mission: to carry out a survey of sea turtles that would record, in intimate detail, their identification and nesting sites. In the years to come, Bhaskar, who passed away in 2023, would travel over 4,000 km along the Indian coastline, conducting surveys by foot, discovering crucial nesting beaches. It is this work that makes him such a legend within the wildlife conservation community and an inspiration to generations of marine biologists.

However, few people beyond these circles know much about his work. From almost single-handedly metal-tagging leatherback turtles in West Papua and trying to rescue hatchlings from predators to being chased by a wild elephant—Bhaskar’s life experiences are made for a movie. And now, a dramatised documentary on the veteran marine biologist will tell his extraordinary tale. Directed by Taira Malaney (with James Reed, the award-winning co-director of My Octopus Teacher as the executive producer), Turtle Walker takes its viewers on an adventure that retraces Bhaskar’s journey, and even examines the impact of the 2004 tsunami on sea turtle habitats. The film is backed by Zoya Akhtar and Reema Kagti’s Tiger Baby Films, as well as Academy Award-nominated HHMI Tangled Bank Studios, and premiered at Doc NYC 2024, New York in November and won the coveted Grand Teton Award in 2024.

It took Malaney a few visits to convince the self-effacing Bhaskar to agree to be filmed. “He shied away from the public and didn’t want to be the focus of attention,” explains Malaney, sharing that Bhaskar had no digital footprint either. “He took a long time to warm up. But once he started, he was so passionate about what he did that when we asked him about his work, he would talk non-stop.” Over seven years, Malaney and her team went on to record 26 hours’ worth footage on him alone, as he recounted his extensive process of collecting sea turtle data from 1977 to 1996. For Malaney, Bhaskar’s interview formed the “backbone of the film.”

Track and trace

While alone on Suheli Par, Bhaskar wrote at least 10 letters addressed to his wife, Brenda, which he would put into glass bottles and throw into the sea. One of these wandering bottles arrived in Sri Lanka and was discovered by a fisherman who posted the letter to Brenda in Goa. “The letter travelled 800km at least, and reached Sri Lanka in 26 days,” Bhaskar notes in the film. It was a strange kind of epistolary romance, made for the books.

It was on the island that he saw tracks made by female green sea turtles. From afar, the patterns resembled braided hair, which indicated that the beach was a well-visited nesting ground. However, “it was quite a few days before I saw my first green turtle laying eggs,” shares Bhaskar in the film. Finally, one day, he spotted the large marine creature not too far from his hut. The sea turtle was scooping and flipping sand with her spade-like flippers, and grunting sonorously. The labour-intensive burrowing was so she could lay a clutch of eggs. Such intimate experiences encouraged Bhaskar to make an ambitious commitment “to survey every single beach and every single island and every coast of every single island” in India. Suheli Par would become a pivotal part of his pioneering 19-year research-based journey.