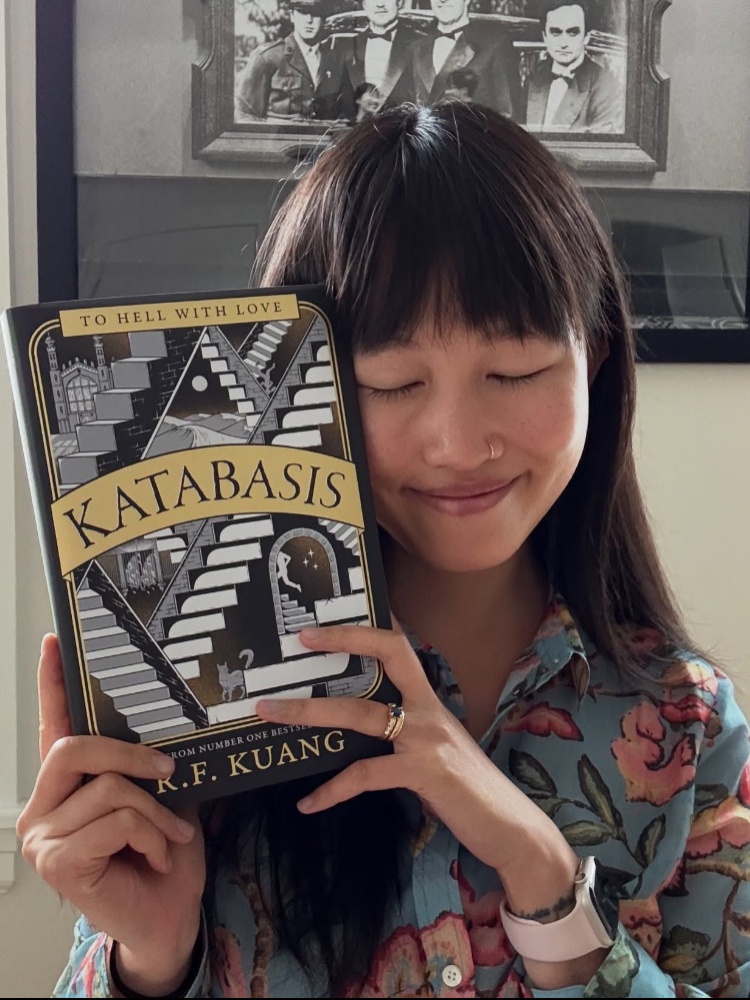

In 2023, RF Kuang became a household name with Yellowface, the biting satire of the publishing industry that had everyone in the book world buzzing, tweeting, subtweeting, and nervously side-eyeing their colleagues. But here’s the thing most casual readers of that novel might not know: Kuang isn’t just a literary provocateur, she’s also a hardcore fantasy writer at heart.

Kuang’s literary career began in 2018 with The Poppy War trilogy, a grimdark epic inspired by 20th-century Chinese history, which fused military fantasy with an unflinching look at colonial violence, war crimes, and the corrosive pull of power. Then came Babel in 2022, a doorstopper set in an alternate 19th-century Oxford, where translation itself became a form of magic, and the university system was revealed as a tool of empire. It was sprawling, intellectual, and devastating.

Yellowface was something of a curveball: a contemporary satire with no magic, no armies, no grimdark battlefields. Instead, it skewered the literary world’s obsession with diversity optics, stolen narratives, and hollow allyship. It was unlike anything we had read by Kuang before, but it was sharp, funny, and excruciatingly timely.

Now, with Katabasis, the author circles back to fantasy. But this isn’t a simple return to form. Instead, here she blends the scathing satire of Yellowface with the mythmaking and magic of her earlier works. The result is something that feels both familiar and new: a campus novel reimagined as a literal descent into hell, where grad students trudge through courts of the underworld in pursuit of their dead supervisor.

The story begins with a catastrophe. Alice Law, a Cambridge doctoral student in analytic magick in the 1980s, has accidentally killed her thesis advisor, the brilliant and sadistic professor Jacob Grimes. His body has exploded in a lab accident, and his soul is stuck waiting for judgement. Without him, Alice’s PhD is doomed. Grimes’s letters, connections, and prestige were her lifeline. So, she chooses the most desperate solution possible: descend into the underworld and drag him back.

Unfortunately for Alice, her rival, Peter Murdoch, insists on coming along. Peter is also one of Grimes’s students, and without his supervisor his future is equally wrecked. The two set off together, reluctantly bound by shared doom. “Hell is a campus,” Kuang writes, and she means it. Their partnership is reluctant and brittle. They despise each other but are bound by the same dependence, the same desperation. Together they trek through the eight courts of hell, each more grotesque than the last, and discover that the real monsters are not demons but the academic systems they have internalised: exploitation disguised as mentorship, rivalry framed as ambition, exhaustion mistaken for prestige.