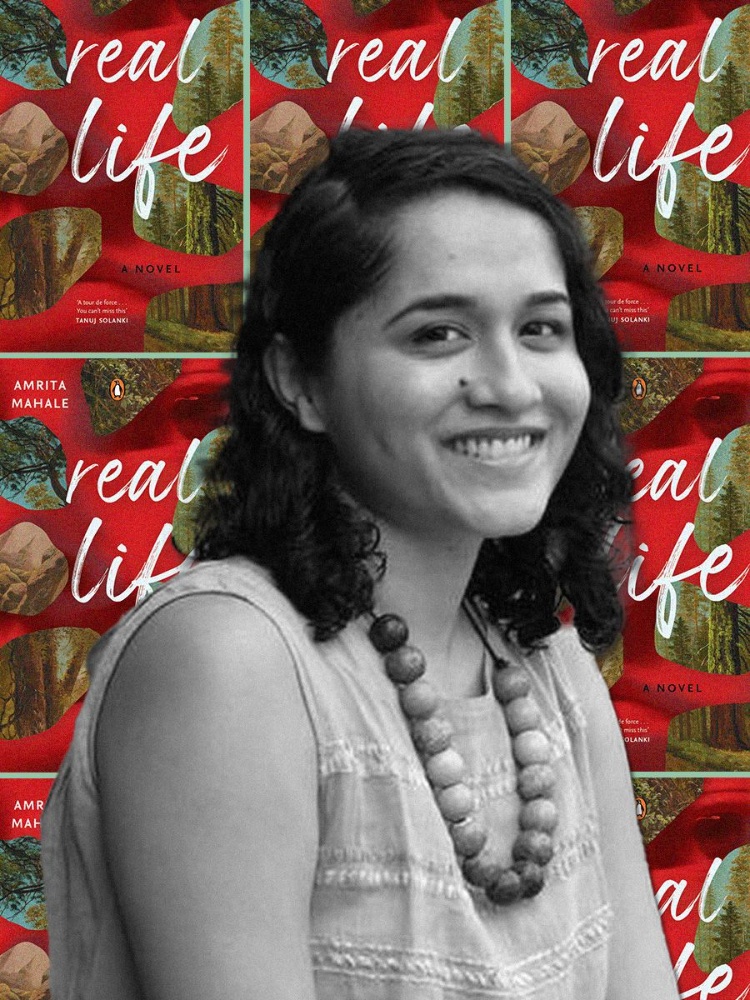

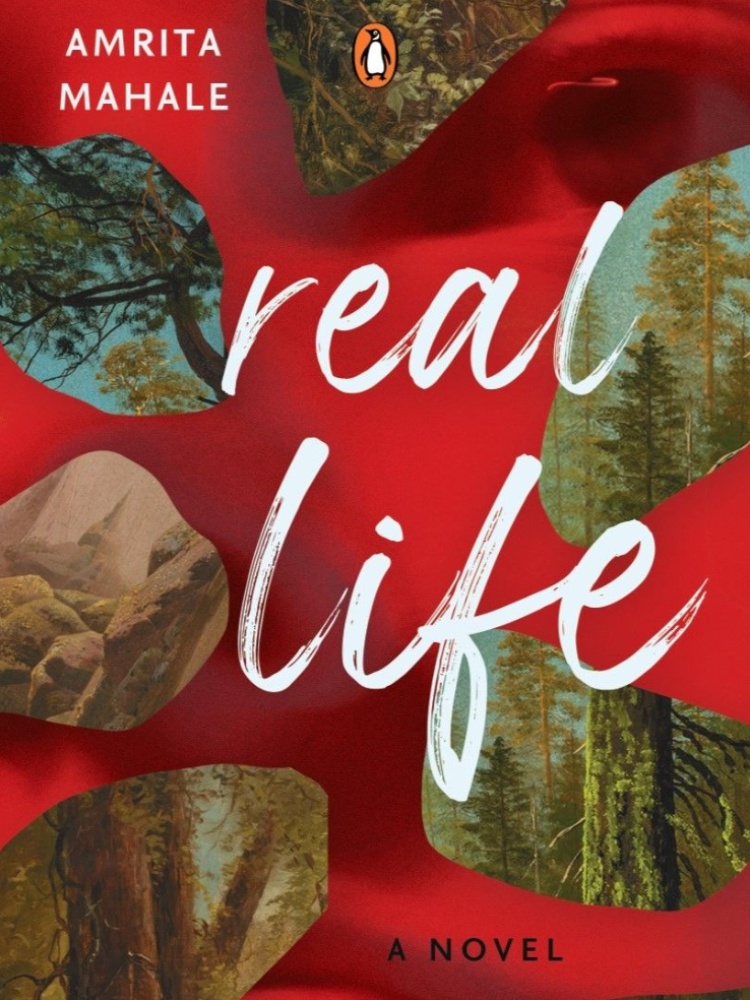

In August 2017, a Swedish journalist, Kim Wall, boarded the submarine UC3 Nautilus to interview Danish tech entrepreneur and local celebrity Peter Madsen in Køge Bay, Denmark. No one heard from Wall again. Months later, parts of her dismembered corpse washed up ashore around the area, and Madsen was arrested and later convicted for her murder. It’s a gruesome incident that lodged in author Amrita Mahale’s mind and sowed the seed for her second novel, Real Life, after 2018’s Milk Teeth.

To be clear, Real Life is not gruesome (even if its opening line would make you believe otherwise: “Your head, they find it last”); the connection between the Denmark incident and the novel isn’t perceptible unless you hear it from Mahale. What the “submarine case” did was make Mahale contemplate the attitudes and undercurrents surrounding the incident and its aftermath. “I knew I wanted to explore male rage, misogyny, how misogyny is internalised by both men and women, and how even women have expectations of how good, respectable women should live and behave,” says Mahale when we meet over a video call on a weekday afternoon.

Mumbai-based Mahale is an aerospace engineer by training and now heads product and innovation at a nonprofit working in the field of child and maternal health. Real Life, The Nod Book Club’s September pick, is, at its heart, the story of a friendship. Mansi and Tara, both from contrasting socio-economic backgrounds, meet when they are seven and become friends, sharing a love for reading, Chitrahaar, fried bread rolls, and the dog name Chunky.

As they grow older, they remain close, even if they are sceptical of each other’s life choices. Mansi’s job involves improving the efficacy of the country’s “third most popular fairness cream”, while Tara decides to do her research project on dholes, or Himalayan wild dogs, in the (fictional) Mahamaya Valley in the foothills of the Himalayas. The jibes and the little cruelties of a lifelong friendship are there, but so is a deep-seated, unperturbed affection. In the middle of her fieldwork, Tara goes missing. The main suspect, Bhaskar, a scientist studying machine learning, is someone with a past connection to both Mansi and Tara, and his interrogation throws up more questions than answers.

Through the three characters, the novel encompasses the aforementioned themes of rage and misogyny but also climate change, overtourism, AI, techno-solutionism and supermodernity—and privilege. Cleverly, Mahale also leaves us little breadcrumbs that play with our expectations of what it means when a woman disappears. There’s a mystery at the centre of the novel, but to call Real Life a mystery novel seems inadequate.

Below, excerpts from an interview with Mahale, where she talks about female friendships in literature, ChatGPT, and tackling privilege in her novel:

The crux of the book is the friendship between Mansi and Tara, before you can explore any other themes. Why did you make female friendship the foundation of Real Life?

I’m a huge fan of Elena Ferrante’s Neopolitan novels. I thought just the construct of a female friendship is a way to explore different ways of being a woman in the world. You have two characters who are essentially witnesses to each other’s lives. So, I suppose that was what drew me to this setup. But then, over time, the friendship became the emotional core, the heart, of the novel. That was not intentional. A lot of this is fairly mysterious. Writing fiction is very mysterious. You start off with a certain objective, but then the process takes over. So, you don’t know why you made the choices you did.

You’ve mentioned that you wrote Bhaskar’s character about six months before ChatGPT was launched. When ChatGPT actually launched in 2022, what was your reaction? Where did Bhaskar go from there?

I was shocked. I was heartbroken, because I thought my novel was now going to seem very pedestrian, which did not end up being the case. An earlier draft of the novel had Bhaskar working on something that’s a bit futuristic; it was a research project. But now, any kid can essentially spin up a chatbot that sounds like another person. I thought that subplot would no longer be interesting, but actually it’s more interesting because it’s something that almost everybody can relate to. It’s not speculative anymore.

The book is divided into three sections, told from the point of view of Mansi, Bhaskar and Tara, respectively, followed by an epilogue. Mansi’s opening section is the only place where you employ a first-person voice. Why so?

With Mansi’s section, I started on page one and I basically just followed the voice. Her voice was very, very clear in my head. In fact, I think I wrote almost the entire first chapter in the first month of writing the novel. The first two months I didn’t move forward at all; I just wanted to make sure I got her voice right. It came from some place deep within.

And I wanted to make Mansi’s section sound a little bit like a soap opera. It’s the most dramatic of the three sections. There are lots of emotional ups and downs. In her interviews, Ferrante talks about how she’s not above using any trick to make the reader keep turning the page. She loves writing page-turners, but she wants to make sure she has the reader’s attention. But once she has the readers’ attention, she’s not going to pander to them. She wants to engage with the reader on her own terms, but first, she talks about the importance of hooking the reader in.

So, I think my intention with Mansi’s section was similar; I wanted to draw the reader in completely. And then the novel gradually becomes more complex. In the first part, it’s not a novel of ideas. The bigger themes of the novel start getting introduced in Bhaskar’s section and then in Tara’s section. I just wanted to make the first section juicy, soapy, fun. And every chapter also ends on a bit of a cliffhanger, almost like a soap opera.

Do you have a favourite character?

Tara. Her section was also the most fulfilling to write. I won’t say the most fun to write, because writing is not very fun. But I really enjoyed writing her parts the most. And I really loved the research I had to do for Tara’s section.

How did you come upon dholes, or Himalayan wild dogs, as a subject for Tara’s field study?

There are two novels that I read a long time ago that have really stayed with me. One is Amitav Ghosh’s The Hungry Tide, and the second is William Boyd’s Brazzaville Beach, both of which feature female biologists. In The Hungry Tide, Piya studies dolphins in the Sunderbans. In Brazzaville Beach, the protagonist studies chimpanzees in Africa. And I just thought it was a way radical choice of occupation for a woman—to be on her own, to navigate the wild, the uncontrolled, the opposite of domestic. So, you’ll begin to see like a theme, a pattern. It was a very different way of being from my own life. That’s what really attracted me. Even in Milk Teeth, Ira had a profession [civic-beat reporter] that let her walk around the city, make sense of the built environment. So, the choice of profession for the characters in my novel is often very strategic, very deliberate, which lets them do certain things and lets me do certain things.