Fashion trains its brightest to move fast. Seasons blur, output becomes proof of worth, and slowing down can feel like disappearance.

But what happens if you choose to exit fashion’s churn? For some former designers, there is life outside fashion, and it can variously be found by a riverbank, a healing room or a recording studio. These aren’t escape stories. They are recalibrations: what happens when ambition is questioned and fulfilment is redefined on one’s own terms.

"I still love designing, but I don’t want to run a business”

When Malini Ramani, 56, debuted in 2000, Indian fashion was still taking its early, tentative first steps. Her clothes were not. She made resort wear that didn’t ask permission—kaftans cut close to the body, plunging U-necklines embroidered with shells and mirrors, animal prints that prowled the parties of New Delhi, and dresses slit high, worn low. All of it arrived with confidence.

For nearly two decades, Ramani built a loyal following, running two shops. Her Goa store, especially, became a landmark during its 19-year run. “I was crazy about it,” she says. “I used to go straight there from the airport.” Designing, curating, and running the shop was a full life until the balance tipped. “It wasn’t about designing anymore,” she says. “It was the fashion business. A whole machine I wasn’t good at and wasn’t interested in.” Overheads rose, stress followed. “Do I want to do this for the rest of my life? No way.”

The shift changed her sense of authorship. Labels mattered less. “I’m just channelling Shree,” she says; it’s her word for creative energy.

She came to Rishikesh in early 2020 for a short Kundalini yoga training course. When the Covid-19 lockdown hit, she stayed. “If somebody had told me then that I’d be living here five years from now, there’s no way I would have believed it,” she says. “That’s how I live my life—intuitively.”

Malini Ramani at her shop, Maa Malini, in Rishikesh

Now Ramani lives five minutes from the Ganga and runs Maa Malini, a 100 sq ft shop where she sells coconut-scented incense, tarot cards, crystal keychains, handmade scrubs, and brocade caps and sneakers made from leftover fabric sourced from Sumant Jayakrishnan. The proceeds are shared with activist Anjali Gopalan’s animal shelter. “The name is tongue-in-cheek,” she says with a laugh.

Ramani blends perfume oils by hand in small batches, often during the new moon. The range is called Shakti and “the magic ingredient is Ganga jal”, she says.

But she hasn’t stopped designing. “I still love designing; my clothes are my personality. But I don’t want to run a business.” Now she works with one tailor and one embroiderer, making shamanic capes, ponchos, sweaters and zip-up saris in very small runs.

Days begin with walks to the ghat with her dog Lucy (“it’s like an addiction”), followed by meditation, shop time, and retreat planning. Fulfilment isn’t about scale or visibility. “Number one is freedom,” she says. “Learning, growth, community.” No scrambling, no fashion-week-related anxieties. “Is that being a designer?” she asks. “Not for me.”

"First, I was dressing the body. Now I’m repairing it”

“For me, it really felt like the end of a cycle,” Mathieu Gugumus Leguillon says. “Not in a dramatic way. It was just…done.”

Now 47, Leguillon lives in London and works as a soft tissue therapist, a slow, physical, and service-led discipline. Hands that once coaxed ikat and silk into shape now listen for knots and stored memory in the body. “I fulfilled what I had to fulfil,” he says. “I don’t have regrets. I don’t miss fashion. I’ve moved on to something more aligned with who I am now.”

A decade ago, Leguillon was head designer at Bungalow Eight in Mumbai, shaping one of India’s most cosmopolitan labels alongside Maithili Ahluwalia and Isla Van Damme. Before India came Paris, Lanvin, and a childhood certainty that fashion was the plan. At Bungalow Eight, India embraced him, offering rare freedom to experiment and work with crafts while building whole collections. “It was the experience of a lifetime,” he says.

The shift away from fashion wasn’t dissatisfaction so much as redirection. After a difficult emotional spell in 2012, yoga and meditation pulled him inward; he quit smoking. “It shifted the angle from which I was looking at the world,” he says. Fashion loosened its grip.

Mathieu Gugumus Leguillon at work as a soft tissue therapist in London

When he left Bungalow Eight in 2015, a small inheritance gave him time to travel. In Mysuru, at the Pattabhi Jois Ashtanga Institute, he stumbled into a massage course. What started as curiosity became a calling. In London, he retrained at Regent’s University as a soft tissue therapist. Around the same time, he learned of a lineage of healers within his own family—father, grandfather, great-grandfather. “I felt I had this gift as well.”

“First, I was dressing the body. Now I’m repairing it,” he says. “I don’t see them as opposites at all.” For Leguillon, it’s evolution: the creative instinct remains, redirected with humility.

He’s candid about once being a people pleaser. As a designer, juggling everyone’s visions scattered his own. Now, being adaptable finally serves him. “This is a real labour of love,” he says.

The biggest shift was stepping out of the spotlight. “Fashion really wants you to be a performer,” Leguillon says. Stepping away meant breaking away from that. “What I do now is not about me,” he says. “It’s about helping others.” Fashion, he reflects, “got replaced by another passion, for un-fashion”.

“I don’t look for answers. I look for the questions”

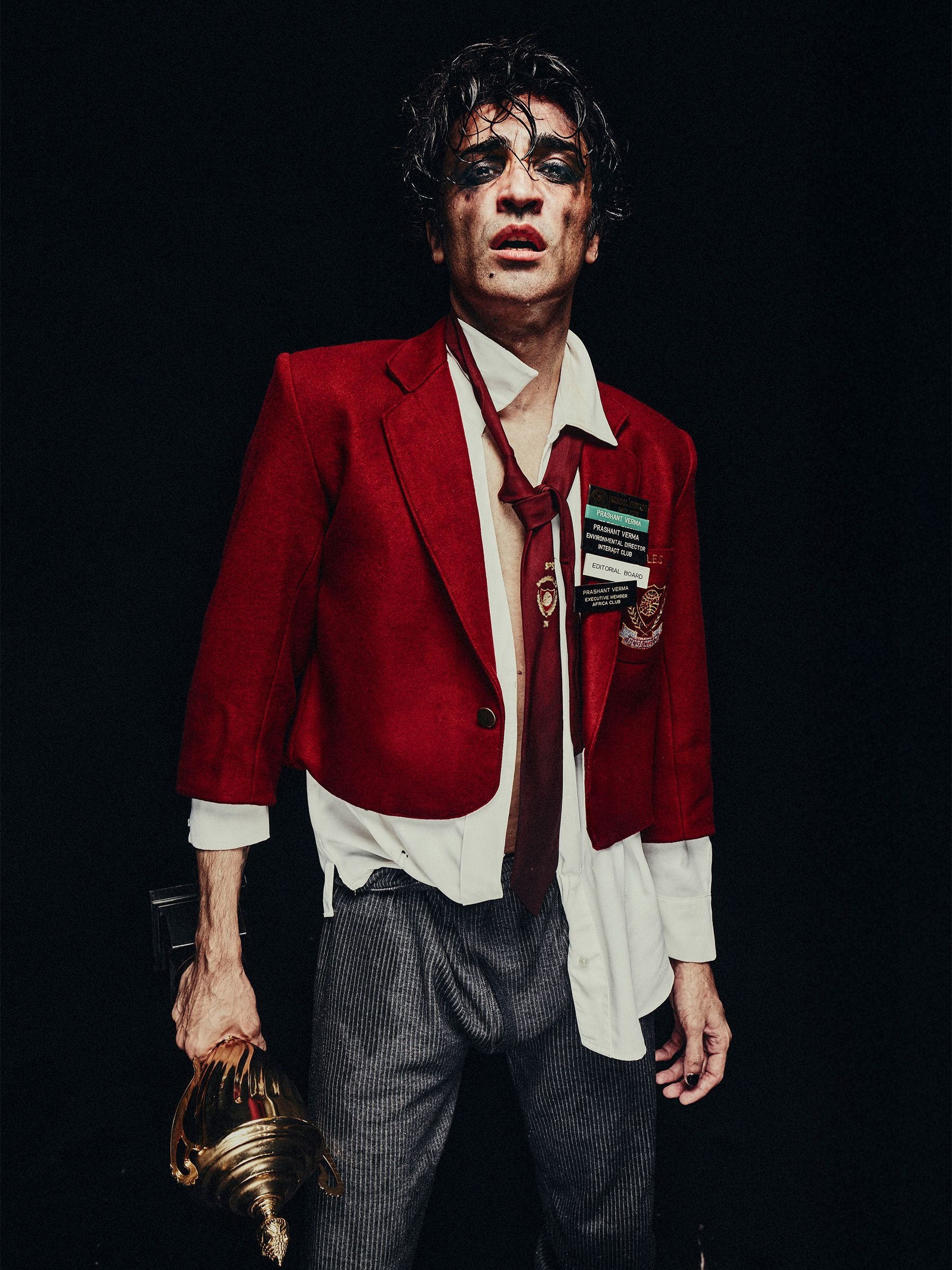

Prashantt Verma’s new single, ‘I’ll Find a Way’, circles a hard truth. It examines ambition and survival, how struggle becomes identity. It’s his seventh release; the full album is out next April, and the track is dark and cinematic. “We mistake the battle for who we are,” he says. “That’s the unhealthy part.” In a world that prizes endurance, stepping away is often read as defeat.

That question—when to fight and when to let go—has followed Verma across his work. In 2007, when he debuted his eponymous label, the clothes never stood alone: narrative, music, and a clear beginning, middle and end all mattered. His much-discussed portrait dresses, misread as provocation, were “mirrors”, he says: “reflections on fame, legacy and release, threaded with pop culture and performance.”

Verma grew up in the 1990s, when art had no hierarchy. Galliano and McQueen, Madonna and Marilyn Manson, theatre, film, MTV—everything arrived at once. Fashion became a container for multiple impulses, holding sound, image, and performance together. In films, clothes linger like souvenirs—“the red shoes in The Wizard of Oz don’t carry the message, but they stay.”