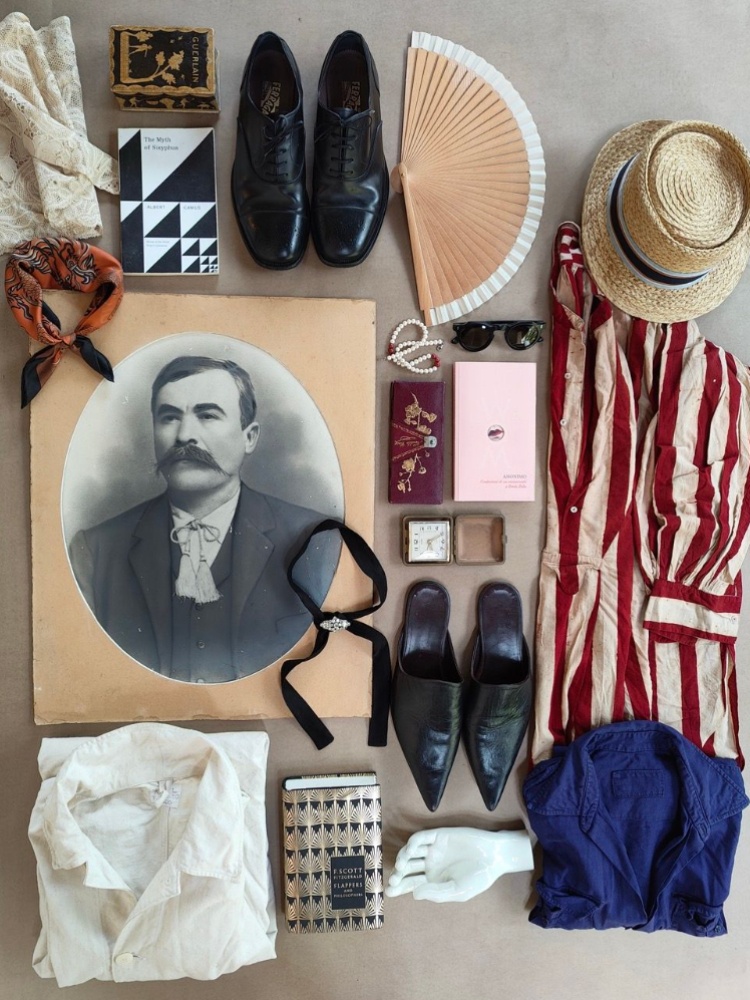

Silk cravats. Sharp lapels. A smirk worn like fresh cologne. Dandyism has always been about more than just a man in a good suit. It’s a cultural cipher—rooted in rebellion, race, and identity. At first glance, the dandy is a vision of elegance. But look closer, and you’ll see a more subversive silhouette: someone dressed not merely for admiration, but to challenge the colonial gaze. Nowhere is this more evident than in the African-American community, something that has inspired the Costume Institute’s new exhibition, ‘Superfine: Tailoring Black Style’, spotlighting the influence of the black dandy over the past 300 years and this year’s Met Gala dress code, ‘Tailored for You’—scheduled for May 5.

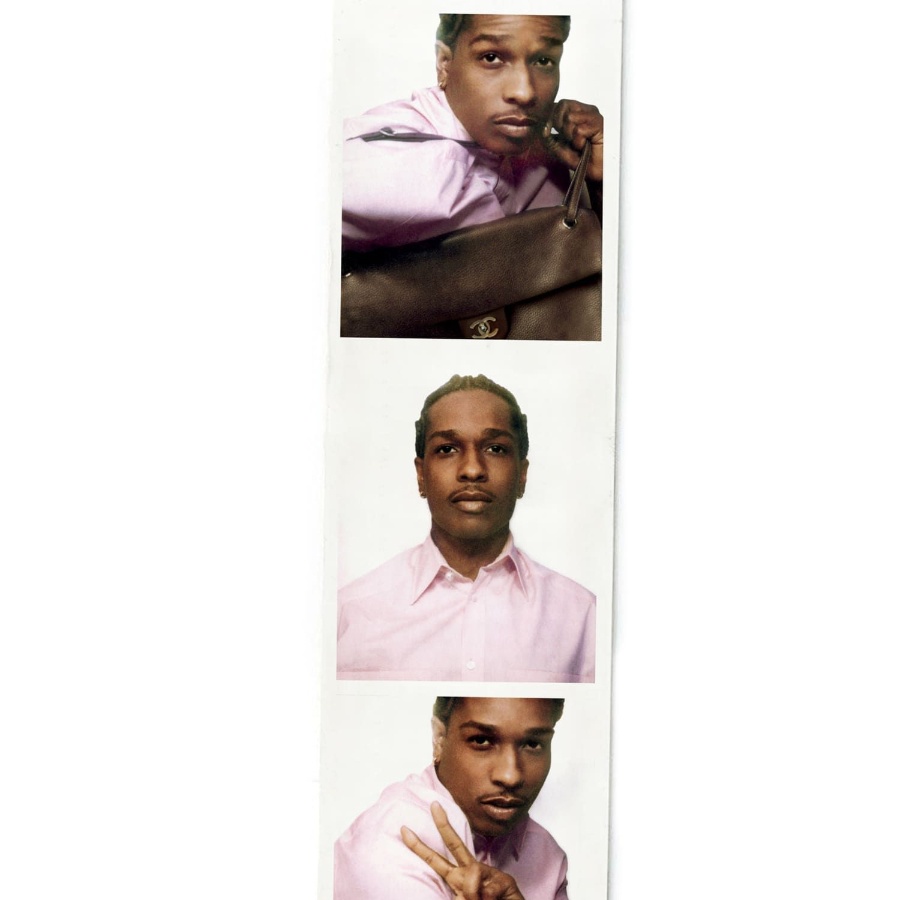

While the co-chairs of the Gala—Colman Domingo, A$AP Rocky, Lewis Hamilton, and Pharrell Williams—perfectly embody the modern dandy, dandyism is a magpie movement that picked up elements along its long route. The phenomenon reached its crescendo in the 1980s and 1990s when American fashion designer Dapper Dan flipped the luxury industry inside out by reimagining high fashion for hip-hop. He dressed rappers like Jay-Z and LL Cool J in upcycled Gucci, Fendi, and Louis Vuitton, long before those maisons even acknowledged street culture. But before him, there was 19th-century social reformer Frederick Douglass, who understood the semiotics of tailoring deeply. “A man’s character always takes its hue, more or less, from the form and colour of his dress,” he once proclaimed—a philosophy that travelled far. Across the Atlantic and into colonial India.

The Indian context

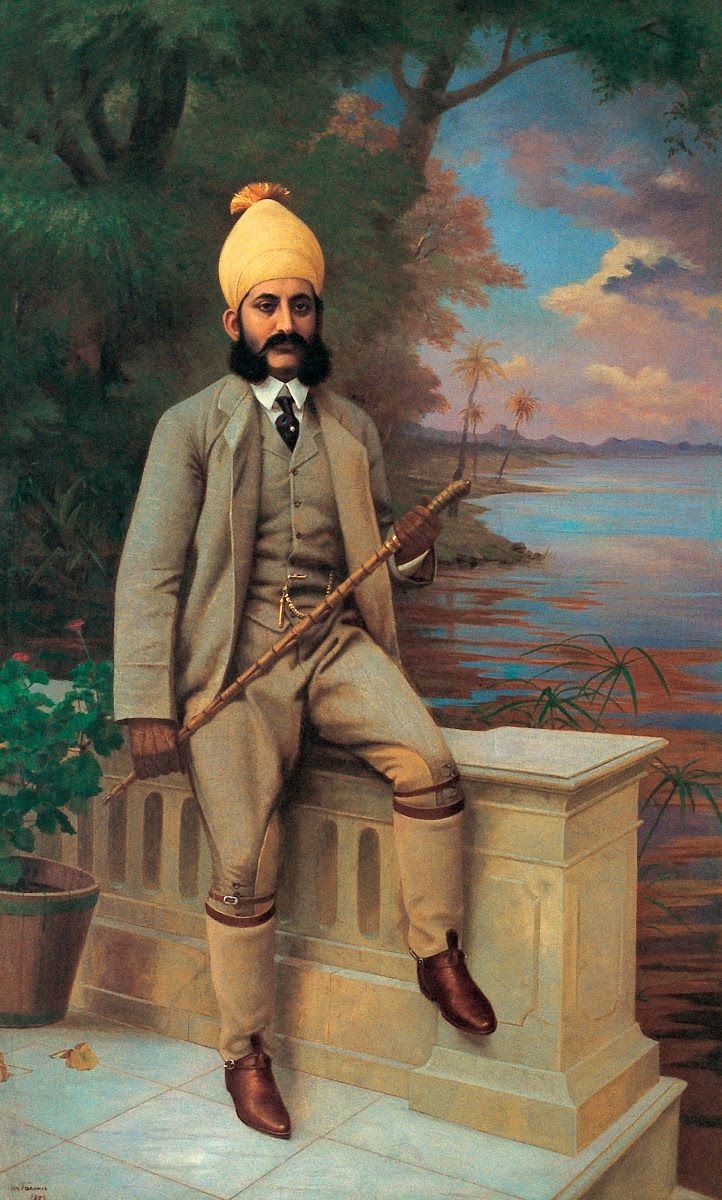

In India, dandyism was more than resistance. It was a reclamation. Even before the arrival of the British, Indian aristocracy already had a deeply entrenched grammar of menswear codes. The Mughals perfected this vocabulary with fabrics that were lighter than air and precious jewels that mirrored the stars. Clothing wasn’t excess, it was an expression—of lineage, of divinity.

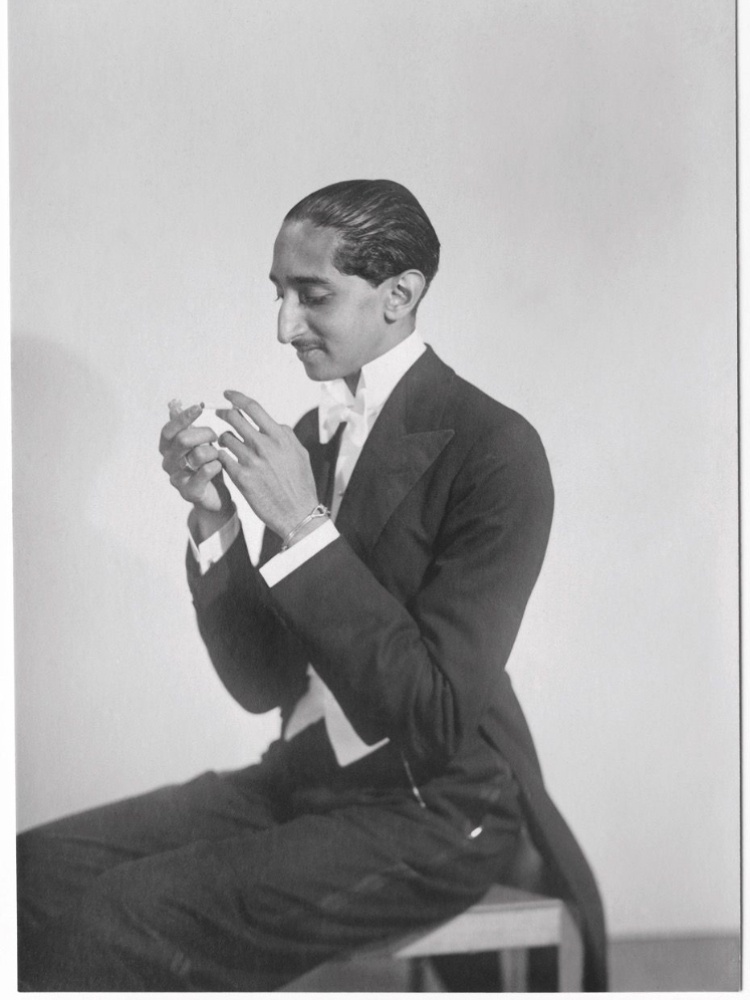

British rule introduced fine tailoring but not taste. Indian men began to adapt Western silhouettes not to assimilate but to unsettle. Enter the princely dandies. Men like Maharaja Yeshwant Rao Holkar II of Indore, whose portraits by Man Ray and Cecil Beaton could rival any Bond-era European aristocrat. His wardrobe—filled with Cartier accessories, Savile Row suits, and custom sherwanis—was a study in duality. Elsewhere, Mahboob Ali Khan, the sixth Nizam of Hyderabad, was known for never repeating an outfit, while Wajid Ali Shah, the last Nawab of Awadh, wore his signature angrakha with one panel exposed. Even outside the royal courts, stylish men were instantly recognised by their penchant for muslin kurtas and betel-stained lips—something that Vātsyāyana’s Kama Sutra has described as one of the most attractive things a man can do.